Is America Really Ready for a Third Party?: Many voters are feeling anticipatory disappointment about the prospect of a rematch between Joe Biden and Donald Trump. In a country this big, surely we can at least come up with some fresh faces. With voters unhappy with a long and ugly repeat – and such wide polarization between the two major parties – it’s no wonder more people wish for greater choice.

A Gallup poll released this month found that 63 percent of Americans agree that the two main parties do “such a poor job” representing the public that a third major party is needed. That’s a record high. It’s not a huge jump from recent years, but still represents substantially increased dissatisfaction from 20 years ago, when only 40 percent favored a third party. A Pew poll released last month found that a similar-sounding 63 percent of Americans have little to no confidence in the political system heading into the future, with only 4 percent believing the U.S. political system is working well.

Negative views about the parties are only growing. Perhaps as a result, Americans are increasingly identifying themselves as independent. Last month, Gallup found that 46 percent consider themselves independents, with both Republicans and Democrats in the mid-20s. The share of independent or non-affiliated voters has been growing in states where citizens register by party. In Florida, for example, the number of people who register under “no party affiliation” or with minor parties now tops 4 million, which is a half-million more than back in 2017. Heading into this year’s governor’s race in Kentucky, growth in new registrants who are independent is outpacing both Republicans and Democrats. Ahead of legislative elections next month in New Jersey, more than 8,000 people registered as unaffiliated last month, compared with 1,300 new Republicans and a net decline among Democrats.

A majority of people believe that conflicts between Republicans and Democrats get too much attention, as opposed to focusing on real issues, according to the Pew poll. But while there’s widespread disgust about the level of partisan rancor, most people tend to vote for one party more often than the other. That’s an old truism in political science – independents tend to vote like partisans – but nowadays people are increasingly unlikely ever to split their tickets. “The basic paradox is that on the one hand, the number of people who are expressing dissatisfaction with the political system is at record highs, but at the same time, the number of people who are voting to re-elect their incumbents is also at near-record highs,” says Lee Drutman, author of Breaking the Two-Party Doom Loop: The Case for Multiparty Democracy in America.

One of the paradoxes of polarization is that, although more people say they’re dissatisfied and want more than two choices, the two parties are so far apart on nearly every issue that there’s too much risk for most people to vote for an independent or third-party candidate. They might not like either party, but they’re too afraid of the party they like least taking control to “throw away” their vote on a candidate who can only act as a spoiler.

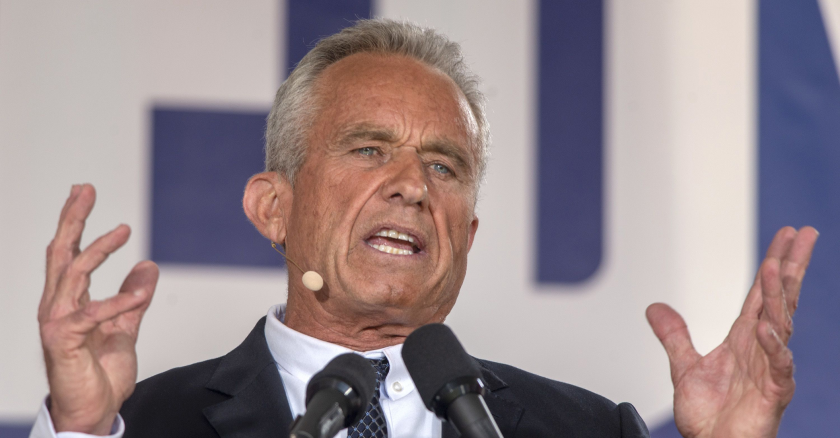

In the presidential race next year, independent candidates Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Cornel West and the eventual No Labels nominee will almost certainly finish in the low single digits. The Biden campaign will certainly be making the case that a vote for any of them is effectively a vote for Trump. They’ll try to raise the stakes of such a choice by noting that the last two elections were decided by a total of less than 80,000 votes in the three closest states, with third-party candidates almost certainly contributing to Trump’s win in 2016.

It's not healthy for a democracy when a majority of people are so dissatisfied. But while they may express disdain for both parties by declaring themselves independent, ultimately most people fear and loathe one party more than the other.

“To the extent people don’t like either party, they think one party is worse,” says Drutman, a senior fellow at New America, a think tank in Washington. “There’s no real way to express dissatisfaction with your own party. You can’t vote for the other party because 90 percent of districts and states are locked in for one party or the other. You’re trapped.”

Brandon Presley, a member of the state Public Service Commission and the Democratic nominee, has sought to make the case that Reeves is corrupt. He’s tried to tie the governor to a welfare scandal that saw $77 million in federal funds redirected to pet projects sponsored by well-connected individuals in the state. Former NFL quarterback Brett Favre, who’s been implicated in a civil lawsuit, was scheduled to be deposed this month, but that’s been pushed back until December, after the election. There’s as yet no smoking gun linking Reeves to the scandal. The robbing of the poor to fund the rich happened under the previous administration.

Lately, Presley has sought to make an issue of state contracts received by Reeves’ sister-in-law. "Tate Reeves’ family business is corruption – and it's wrong that his family has personally profited from hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxpayer contracts during his time in office," Presley said recently.

Presley has made Reeves’ opposition to Medicaid expansion central to his campaign, but last month the governor announced changes to Medicaid reimbursement formulas that he says will boost Mississippi hospitals’ income by nearly $700 million annually. Reeves has been able to take credit for historically low unemployment, as well as the “Mississippi miracle” in education. While test scores around the nation have been cratering, reading scores in Mississippi have jumped up.

Back in the spring, polls indicated the race was either close or tied, but Presley hasn’t been able to gain enough traction to take advantage. He’s had to introduce himself to voters outside his base in the northern part of the state and – being conservative on most issues – he’s failed to fire up Black voters. “The African American vote is not enthusiastically behind Presley, and without the African American vote, he’s in trouble,” says Stephen Rozman, a retired political scientist at Tougaloo College in Jackson.

In the end, Presley hasn’t been able to convince Republican voters that they’d be better off with a Democratic governor. Many of them don’t like Reeves, but they’ve mostly come home to him. A Magnolia Tribune/Mason-Dixon poll released last week showed Reeves ahead by 8 percentage points. More importantly, it showed him winning with the right groups to win in Mississippi, carrying men, older and white voters, independents and 92 percent of Republicans in a state that Trump carried in 2020 by 17 percentage points.

“When push comes to shove, what are they going to do?” Rozman says. “Even though Reeves’ support may decline, I’m not seeing large numbers of Republicans who are going to switch parties and vote for the Democrat, Presley.”

(CommonCause.org)

The report touts what the groups count as success stories – notably, maps drawn by independent commissions that don’t include elected officials or give them appointment power. Grades range from the top mark of A- for California and Massachusetts to grades of F for seven states – Alabama, Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee and Wisconsin. But even in cases where political actors were seeking self-gain, “organizers could shame officials into doing the right thing for their communities,” says Dan Vicuña, redistricting director for Common Cause and a co-author of the new study. “That was a pleasant surprise.”

(CHARGE / commoncause.org)

That said, there were lots of disappointments as well. Litigants challenging the Illinois House map made the case in court that the voting power of Black residents in East St. Louis had been diminished, but a judge allowed the gerrymander to stand because legislators’ motivation was partisan, not racial. That came after the map had been previewed for House members “behind literal locked doors,” a moment emblematic of the limitations on public input into the chamber’s process. “Illinois represents a nearly perfect model for everything that can go wrong with redistricting,” the report concludes.

How to make things better? Organize early, says report co-author Elena Langworthy, deputy director of policy at State Voices, a voting rights network. The public is increasingly aware of the importance of redistricting, she says, but education on the issue should be combined with census count efforts so people understand how the two are tied together in terms of winning substantive resources for communities.

Accessibility was a particular challenge during this redistricting cycle. Hearings were often more rushed than usual due to the accelerated timeline caused by census delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Those dynamics will change in the next decade, but the desire of politicians to carve out favorable districts will not. For that reason, Langworthy suggests, it’s not too early to think about 2030.

Previous Editions

-

Louisiana attorney general Jeff Landry is the clear favorite to succeed Gov. John Bel Edwards, but will he prevail? Meanwhile, there seems to be no end to redistricting fights as prominent cases continue in Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, New Mexico and New York.

-

Virginia is one of just two states in which legislative control is divided between the parties. Then, what makes special elections so special, Pennsylvania Democrats' struggle to maintain control and attorneys general keep getting in trouble.

-

Why has the state's Republican Legislature descended into chaos and hostility? Plus, it's probably too late to beat Trump and Richard Russo and the humor of mergers.

-

This week in state and local politics: San Francisco Mayor London Breed is in real trouble while there's handwringing over hand-counting ballots.