(Photos by David Kidd)

Their fortunes and identity once dependent on coal, they have been decimated in recent decades by the collapse of the mining industry. After the disappearance of mine-related jobs came the loss of their high schools, a major university, most of their businesses and a sizable percentage of the population. But by eschewing competition in favor of cooperation, the municipal neighbors have begun to turn things around.

Smithers Mayor Anne Cavalier and Greg Ingram, her counterpart across the river, have established a formal partnership between the two communities. By joining forces and sharing resources, Smithers and Montgomery are reinventing themselves and their economies. “It’s been the best thing we’ve ever done,” says Mayor Ingram. “People see the things that we’re trying to do together, and I think they have hope now. They’re starting to have hope.”

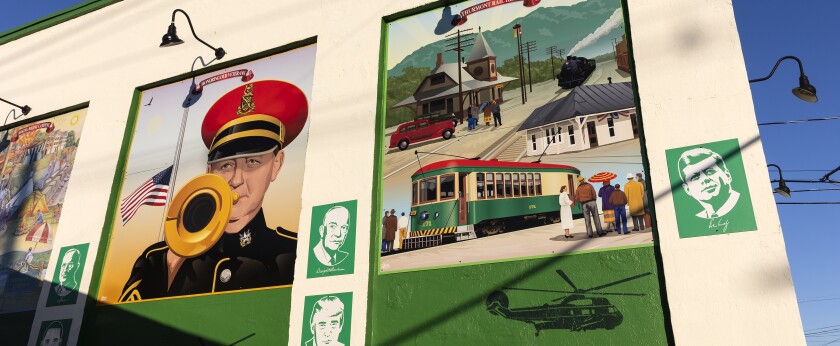

Originally known as Coal Valley, the town of Montgomery was incorporated in 1891. Early growth followed construction of the Kanawha & Michigan Railroad, establishing the town as a shipping center for more than 20 different coal production operations.

Mining once brought prosperity and employment to Montgomery, but environmental regulations, mechanization and market forces combined over time to hollow out the workforce and the population. Today there are 1,500 people still residing in Montgomery and another 850 in Smithers, less than half of the number who lived there in the 1950s. Trains still run through Montgomery on a regular basis. But instead of carrying coal, they are just as likely to be transporting tankers full of Bakken crude.

The Good Old Days

Beach Vickers was born in Montgomery, back in 1950. After graduating from college, he began his adult life abroad as a Peace Corps volunteer, followed by decades of theater work in Florida, New York, California and Texas. Beach returned to his hometown in 2018. He has roots here. His father was Earl Vickers, the local bridge’s namesake. “Going back a little bit … I am one of the Montgomerys,” he says. “THE Montgomerys.” Today he divides his time writing grant proposals for the town of Smithers and working for the police department.

Beach Vickers and John Scalise are typical of a local population that skews older. Among the town’s elders, Byron Rowsey, 92, is the most well-known. He recently celebrated 71 years of selling men’s clothes, the last 50 from his full-service shop in Montgomery. His business has survived, he says, because his customers come from well beyond the town’s borders. “It was great,” he says, describing the downtown of 50 years ago. “There were 84 different businesses. You couldn’t get a location in this town. I don’t care who you were.”

School’s Out

Founded in 1895 in Montgomery, the West Virginia University Institute of Technology (WVU Tech) began as a college prep school, changing its name and mission several times over the years. Citing deteriorating infrastructure and declining enrollment, the school relocated in 2017 to the equally troubled but slightly larger town of Beckley, over the vociferous objections of the community. “WVU Tech was born here. It was raised here,” says Mayor Ingram. “And the bandits came and took it.”

Mayor Cavalier refuses to say the school moved. To her, Tech was closed, and another school opened in Beckley. “We watched as the U-Hauls left town,” she says. “We watched this town empty out. And it emptied out of Smithers too, because a lot of the students had apartments in Smithers.”

The university’s departure was followed two years later by the closing of the last local high school, Valley High in Smithers. “It’s very important to talk about the Tech exit,” says Ingram. “But then the high school. Then Kroger’s decides to leave. Then the car dealership. And the furniture stores. ...”

Two Mayors With a Mission

Now serving a second term, Greg Ingram was the town recorder before being elected mayor of Montgomery in 2016. He retired from a 43-year career with the Caterpillar heavy equipment company in 2019. When not in his office at the converted bank building that serves as City Hall, he can be found roaming the streets in his brand-new “side-by-side,” an enlarged and enclosed all-terrain vehicle, which he uses to traverse the rutted old mining roads that crisscross the nearby mountains. License tag number 000001 is affixed to the back.

Ingram had been mayor of Montgomery for two years before Anne Cavalier was elected in Smithers. She comes from a long line of public officials, including a mayor, recorder and more than one council member. “In Smithers, it’s hard not to get a Cavalier in public service,” she says. She spent 25 years teaching at Tech as a tenured faculty member in the College of Business and Economics. “We come from two totally different backgrounds,” says Greg Ingram about his counterpart. “I always say Mayor Cavalier is the polished one, and I’m the street fighter.”

“But we are learning from each other,” says Cavalier.

“Two Municipalities, One Community”

These days, citizens of both towns routinely cross the river to shop, eat, go to work or attend school. It is not unusual to see the uniformed Montgomery chief of police behind the wheel of a Smithers police SUV on weekends, making a little extra money. It’s not surprising, then, that the towns would someday consider a more formal arrangement. And that is what they have done.

Even before Anne Cavalier assumed office, she and Mayor Ingram had been discussing plans for some sort of joint operating agreement between the two cities. To that end, in 2018 they created the Strategic Initiatives Council (SIC), the first official intergovernmental entity of its kind in West Virginia. The best way forward, they reasoned, was to think of themselves as “two municipalities, one community,” solving mutual problems and pursuing common goals by working together.

“When we broke out the ‘M’ word, the ‘merge’ word, everybody was ‘not in my sandbox,’” says Ingram. “We never mention the ‘M’ word,” says Cavalier.

Sharing Resources

The Strategic Initiatives Council meets monthly at the Smithers Gateway Center, a former school that now houses municipal offices, the police department, a health clinic, child care and a senior center. Besides the mayors, the SIC includes two council members and two business owners from each town. With both places in a financial bind, pooling resources is a priority. To that end, the SIC employs a code enforcement officer who serves both, and an extension agent with West Virginia State University who assists with grant writing and economic development. “Neither city could afford a code enforcement officer on their own,” says Ingram. They also share sanitary employees.

The Strategic Initiatives Council exists to do more than share expenses. The organization’s efforts are also focused on improving the area’s quality of life. When members of the two communities come together, ideas are shared and common goals are addressed. “Yeah, there are economic needs,” says Mayor Cavalier. “But I think the economy will grow because you will attract the kind of people that want to have a vibrant economy. We’ve recognized that in order to survive, we have to work together.”

Even so, the mayors remain careful to avoid characterizing the partnership as a merging of their towns. “Mayor Cavalier does her thing in Smithers and I do my thing in Montgomery,” says Ingram. “And then we do things together.”

From Mineral Extraction to Tourist Attraction

With an economic history centered on mineral extraction, the former Coal Valley and its sister city are preparing to once again take advantage of the river and surrounding mountains, this time through tourism and outdoor recreation. Instead of shipping coal out, Smithers and Montgomery are positioning themselves as a destination, bringing new people in. Doing so will require a change in culture and infrastructure.

Beach Vickers remembers asking his grandmother what had become of unwanted and worn-out household possessions, including her Model T Ford. “We threw it in the river,” was always her reply. In the early days of the 20th century, the Kanawha River served as a dumping place for the towns and the mine operators. “Until recently, Montgomery and Smithers paid no attention to the river,” Vickers says. “To this day, there’s virtually no public access to the river.” But that’s about to change.

Allison Smith is the West Virginia State University extension agent working for the SIC. “I am always thinking about what currently draws people to this area and what we can be doing to make Montgomery and Smithers healthier,” she says. “Day to day, that looks like trying to find grant funding to develop our recreation infrastructure.”

A National Park in Their Backyard

Just 30 minutes from Smithers and Montgomery, West Virginia’s New River Gorge recently became America’s newest national park. With that designation, the two towns are expecting a sizable increase in the number of out-of-state visitors. The new park is within a day’s drive of more than a third of the population of the United States. But the cities plan to be more than a stopover for people on their way to someplace else, selling them supplies, feeding them and putting them up for the night. Outdoor infrastructure is planned or under construction in a number of locations in the mountains nearby. Smithers and Montgomery are expecting to be a destination unto themselves, catering to tourists coming to make use of the miles of dedicated trails for hiking, mountain biking and off-road vehicles. An accessible river will broaden the offerings of things to do.

Better Together

Ami Smith oversees the West Virginia State University extension service, which pays half of Allison Smith’s SIC salary. “I find it so refreshing that these two communities have made the intentional decision to come together and work together,” she says. “The mayors get along so well together, and they really do have the best interests of these communities at heart.”

“I would never tell anyone that we don’t have problems or disagreements,” says Mayor Ingram. “We do. But we don’t throw rocks at each other. If I know I’m going to do something that offends Mayor Cavalier, I’ll call her and give her a heads up. And she does the same for me.”

Travis Blosser is executive director of the West Virginia Municipal League. He is a frequent visitor to Smithers and Montgomery and follows events there closely. “Sometimes the answer isn’t ‘hey, we’re going to have to tax people more,’” he says. “We need to partner with each other to share resources. To go after grants and to go after resources. And to build out our communities so that we’re not two separate entities. Sometimes that’s hard.”

But then he adds, “everyone can learn from the Smithers Montgomery story: collaboration, collaboration, collaboration.”

Related Articles