Some of the evidence on police traffic stops comes from Los Angeles. Between 2019 and 2023, the number of traffic stops there fell by more than 50 percent, the result of reductions in staffing and reluctance to intervene in some cases. During those same years, the annual number of road deaths went from 247 to 337. It would be foolish to ascribe this exclusively to declining police enforcement, but it would be equally foolish to think that changes in policing had nothing to do with it. Cameras would have helped.

One recent study estimated that traffic cameras along one particularly dangerous roadway in Philadelphia prevented as many as 20 crashes per month and up to 1.4 monthly deaths. Speeding infractions reportedly dropped by more than 90 percent after the cameras were installed. Virtually every other comprehensive study has come up with similar results.

A year ago Arlington County, Va., where I live, began placing traffic cameras near its elementary schools. The number of accidents went down at every one of the schools, not drastically, but consistently.

The tragedy of traffic deaths throughout the country is beyond dispute. In recent years they have hovered around 40,000 a year. In 2023, there were nearly 12,000 road deaths attributed directly to speeding. That year, nearly 1,100 deaths were the result of red-light running, along with about 136,000 injuries. In many places, the numbers have been better since the end of the COVID-19 pandemic. But they have rarely gone back down to what they were before the pandemic struck.

We could do something about the problem by using cameras in more places to catch speeders and red-light runners. But much of the country is tentative about doing this, and some places have chosen not to do it at all.

Traffic cameras have been in use in this country since 1987. As of this year, according to the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, 22 states and the District of Columbia had red-light cameras, and 24 plus D.C. were using them on speeders. But the number of roads and highways covered remain relatively small, and 10 states ban red-light cameras, speed cameras or both.

Last year, the Iowa Department of Transportation blocked most jurisdictions in the state from employing cameras to manage speeding violations. The Ohio legislature went further: It enacted legislation banning counties and townships from operating traffic camera programs. These programs have been in existence in many Ohio jurisdictions for years. Now they will be shut down.

In July, a committee of the House of Representatives began moving a piece of legislation that would make the cameras illegal in the District of Columbia. D.C. has more than doubled the number of its traffic cameras in the last couple of years. It’s estimated that more than 95 percent of the district’s traffic tickets are now generated by cameras. But the majority of streets and roads still do not have cameras installed.

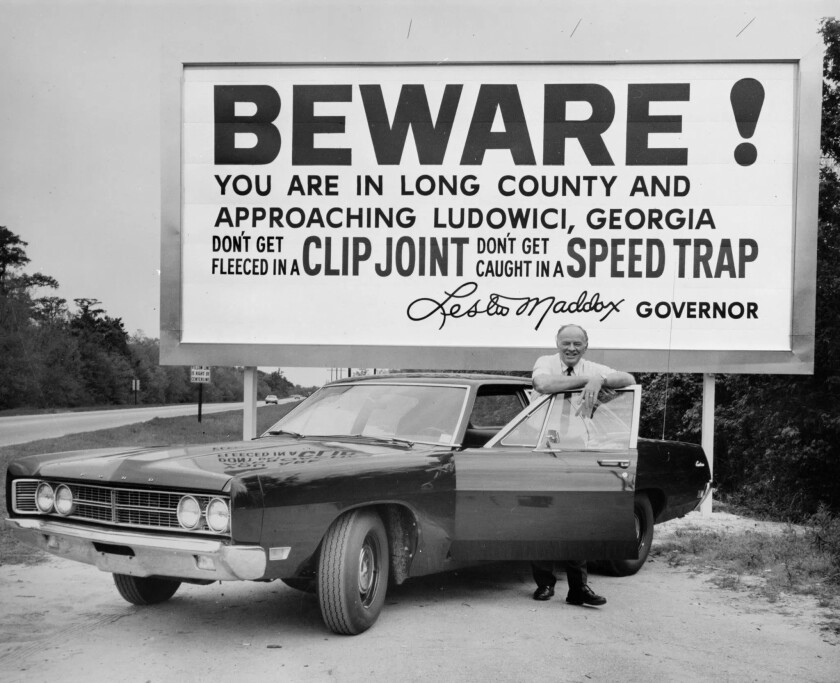

AS IN OTHER PLACES, D.C’.s traffic surveillance has provoked its share of complaints. A good number of them have to do with the practice of suddenly lowering speed limits on streets adjacent to freeway exits. This sometimes reminds drivers of the speed traps that used to be common in small towns and rural areas. But they can exist in big cities as well. A few years ago, I was ticketed by a camera for driving 39 miles an hour in a 25 mph zone. This seemed a little unfair, as I was just coming off a high-speed freeway. I grumbled, but I sent in the money.

Other drivers bear more of a grudge. Perhaps the biggest source of resentment against traffic cameras is the money they bring in to local governments. They have generated a vocal opposition that argues that the surveillance exists more to generate revenue than to ensure safety.

In a report issued last year, the Fines and Fees Justice Center declared that “when payment of a fine or fee becomes the metric by which successful enforcement is measured, revenue generation rather than safety becomes the focus. Those who are unable to pay their fines quickly enough can also face sanctions — including license suspensions, warrants, or even jail — while wealthier drivers can simply pay up and continue to drive.” Tim Curry of the Justice Center has argued that the expansion of automated traffic enforcement “simply created a new and more effective way to fine exponentially more people.”

There’s no question that the cameras can be lucrative. D.C.’s chief financial officer has predicted that enforcement cameras will bring in $1 billion over a period of four years. The cameras on K Street coming off the Whitehurst Freeway, where I was caught years ago, took in more than $4 million during the first half of 2024 alone. But they aren’t the prize winners. A relatively new camera installed at a busy intersection on the Potomac River Freeway reaped nearly $5.9 million in the first half of 2024.

And motorists driving out of the district won’t find relief from surveillance. One study of neighboring Maryland found that the state had taken in $64 million from speed cameras in a single year. One jurisdiction, Montgomery County, was responsible for nearly $16 million of this revenue.

The new speed cameras in my own community of Arlington, with a population of slightly more than 300,000, issued fines to more than 7,000 motorists between last September and this January, raising more than $713,500. That’s a small share of a total county budget of $1.69 billion. But it still strikes quite a few people as a lot of money.

The worst of those situations are, fortunately, long gone. But the perception of unfairness has never gone away. And like all the criticisms of traffic cameras, it contains a certain amount of truth. Yes, they can be placed in carefully chosen positions to maximize revenue as well as (or maybe sometimes more than) promoting safety. They do impose a greater burden on the poor than on the wealthy. They are an offense to those who feel they are being targeted unjustly.

Yet all this has to be weighed against the well-documented evidence that the cameras and the resulting fines reduce the number of accidents and save a significant number of lives. The Insurance Institute for Highway Safety concluded that red-light cameras in 57 U.S. cities saved approximately 1,300 lives over a 22-year span.

I get the complaints. I’m sympathetic to some of the arguments. No one wants to get a notice in the mail fining them $100 or more for an offense they feel they had little chance to avoid. But when you add it all up, saving lives is more important than traffic tickets. If I get fined again for excessive speed coming off a freeway, I may curse the unfairness of it all. But I will send in a check to pay the fine. And I will try to be more careful the next time.

Governing’s opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing’s editors or management.

Related Articles