In Brief:

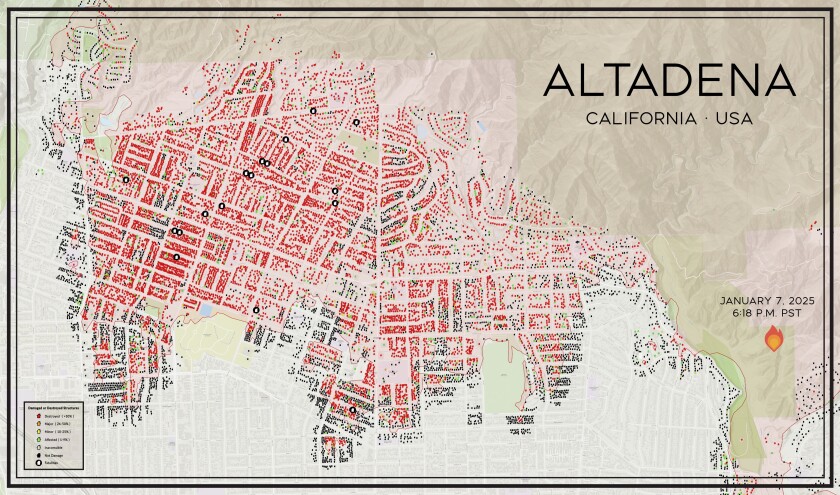

- More than 9,000 Altadena, Calif., structures were destroyed by the Eaton Fire. The scale of this loss is difficult to grasp, even for those who live there.

- A local resident created a large map showing where the fire destroyed homes and took people’s lives. The map is posted outside an Altadena business that survived the fire.

- It has become a touchstone for residents, educators, community groups and government leaders — a powerful and enduring reminder of what was lost.

It’s been nine months since the Eaton Fire ravaged Altadena, destroying more than 6,000 homes and nearly 100 businesses. For many, the fire has been mostly forgotten amid a nonstop torrent of national news, but its consequences are still playing out for local residents.

The fierce Santa Ana winds that grounded firefighting tankers and helicopters also prevented aerial coverage of the fire by news outlets. There is no visual record of the event as it unfolded.

Noel McCarthy, a production designer and artist with deep ties to the area, had firsthand understanding of the devastation. He went to neighborhoods consumed by the fire and provided shelter to displaced friends (or their pets). He and his wife created a donation center to gather and distribute essential items and clothing.

Shortly after the fire, he made a work trip to Texas. The wildfires were fresh news, and he was asked about them when he mentioned he was from Los Angeles.

These conversations made it clear the scale of the destruction hadn’t registered. “People’s eyes just sort of glazed over when I would try to describe the severity of what happened,” he says.

Out of frustration, he began to use his phone to show them a map the county had created. Red home-shaped icons marked destroyed properties. “I’d zoom in on a neighborhood, where you’d see a complete wipeout,” McCarthy says. “It was then that peoples’ demeanor changed.”

This still didn’t tell the whole story. The fire had consumed more than 9,000 buildings. The map had real power, but McCarthy could only show a portion of the impact.

“That’s when a kind of light bulb went off,” he says. “I realized I needed to make it big.”

A Gathering Place

McCarthy enlisted help from a graphic designer and a set construction company. They pieced together screenshots from the county map, printing and mounting the full map. The finished product is the size of a small billboard.

While the project was still taking form, McCarthy mentioned his idea to Randy Clement. Clement, a longtime friend, owns the Good Neighbor Bar and wine shop at the northwest edge of the burn zone. An Altadena resident (his home survived), he’d opened the business just months before the fire.

McCarthy had been wondering where the map should be placed. As soon as he told Clement about it, his friend insisted that it belonged in the big parking lot next to his wine shop.

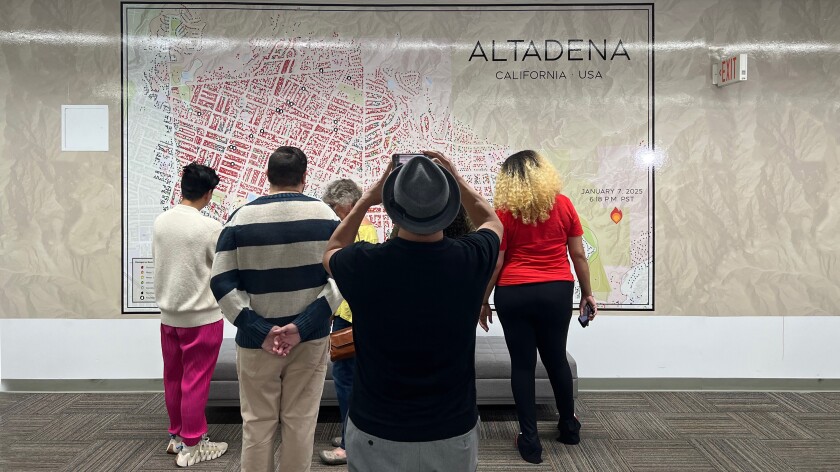

The map arrived on a flatbed truck. “We didn’t even have it off the truck and people started gathering around it, just walking down the street,” McCarthy says.

Clement recalls coming in early the next morning to find a couple standing in front of the map. When they returned to their car, he saw the woman shaking in her seat and realized she was crying. “That was the first moment I realized the power of this map,” he says.

In the months since, the map has been a gathering place for therapy groups, poetry readings, vigils and fire survivors. High school and college groups have come to stand before it, Clement says, as has “anyone running for office.”

On a recent evening, designer Amy Guthrie studied the map with her son and husband. She lives in a nearby section of Pasadena, a city adjacent to Altadena, and is connected to many whose homes were destroyed or damaged.

Guthrie has visited the map regularly since she discovered it. “It doesn’t get easier to look at,” she says. She’s brought friends who don’t live in the area to it.

“They are shocked,” Guthrie says. “You can hear about it [the disaster], you can see pictures, you can drive through it, but the map really gives a complete picture of the impact of the fire.”

Stand and See What Happens

The map was always intended to find its audience and its uses organically, McCarthy says. Clement agrees. “It was made so people can stand in front of it and see what happens,” Clement says.

It has entered a new chapter, now out of the parking lot and mounted on a fence facing Lincoln Avenue, a north-south artery in and out of Altadena. It’s illuminated at night.

“It’s surprising how many people drove by that parking lot every day and never saw it,” McCarthy says. “There’s definitely a different sort of crowd that has been encountering it than before.”

Another map now hangs in the newly opened Eaton Fire Collaborative, created to facilitate coordinated recovery response and communication to those affected.

McCarthy got a grant from the nonprofit Heal the Bay to create a map showing the impact of the Palisades Fire. So far, it hasn’t found a home where it can spark the community engagement seen in Altadena.

Clement has turned his parking lot into a roofed patio, with a play area for children, filled with sawdust and stumps from Deodar cedars felled because of fire damage. Pop-ups from local restaurants serve food under its tin roof.

Clement doesn’t judge people who live elsewhere if they forget about the Eaton Fire. The people on his patio haven’t.

“The idea that there can be a place where people of like mind, experience and emotional state can meet together and look at each other and say, ‘These people understand what I’m going through,’ makes this the most special place we’ve ever built,” he says.