In Brief:

- Pandemic disruptions worsened a long-term trend of declining student achievement.

- Federal leadership has been lacking for the last decade, says Michael Petrilli, the president of a prominent education think tank.

- State-level approaches to reform vary, with differences between red and blue states.

The U.S. has gone a decade without serious national leadership on education, says Michael J. Petrilli, the president of the Fordham Institute, a conservative education think tank.

American youth are the worse for it, he says.

“Our students were already losing ground before the pandemic, and then they went over a cliff,” he says. “Achievement is as bad now as it was something like 30 years ago.”

Petrilli has tracked this evolution for decades. He’s explored trends in several books and as executive editor of Education Next, a journal from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

The Every Student Succeeds Act, signed in 2015, was the last serious attempt at education reform, Petrilli says. “Going back to George H.W. Bush, and then Clinton, Bush and Obama, the nation had a string of presidents who made this a real national priority,” he says. “You can debate some of the actual policies they promoted, but there was leadership.”

Recently, Petrilli decided to look at reform at the state level. “I kept hearing people make the claim that both parties had abandoned education reform,” he says. He wondered if that was true everywhere.

Petrilli recently spoke with Governing about what he found. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Governing: You’re concerned about federal leadership on education disappearing. What about states?

Petrilli: There are a handful of states that you can point to as exemplars that have continued to stay focused on this issue. Mississippi is the one everyone talks about, for good reason. They made tremendous progress in the 2010s, then had a setback with the pandemic like everybody else, but now they've continued to make progress.

You can point to a few other places. Some scholars have recently talked about the “southern surge” because Alabama, Louisiana and Tennessee have shown some progress. There are some examples and some bright spots, but they are the exception and not the rule.

Did you find differences between red and blue state approaches to reform?

I do think you’re seeing a different pattern based on the politics of a given state.

Federal law still requires every state to give annual reading and math assessments in grades 3 through 8, and science once in high school, but the law leaves it to states to decide what to do with the data that comes from those tests.

Almost every blue state said, fine, we’ll follow the law, but we're going to stop rating schools like we used to have to do under No Child Left Behind [a 2002 federal law]. We're not going to make it easy for parents to know if their child's school is failing or not, or excellent or not.

Then you look to the red states. Not all of them but most of them still have something like an A to F or one- to five-star rating system. And those rating systems get released every year. There's often a lot of attention. It's in the press.

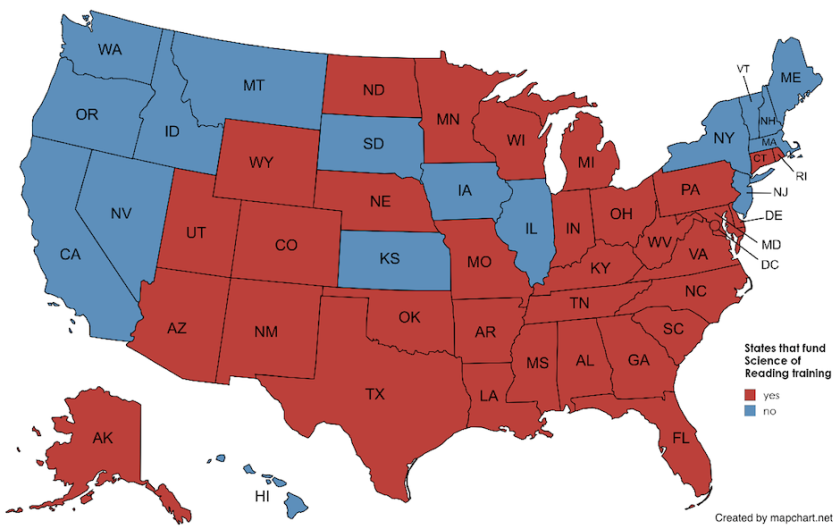

Quite a few Republican states have continued with the education reforms of No Child Left Behind, continued investing in their charter school movements and are getting serious about the science of reading.

You can find a handful of blue states that are doing some of those things as well. But it’s been particularly challenging for the solidly blue states because of the outsize roles of the teachers unions within the Democratic coalition.

(Fordham Institute)

What kinds of changes should be priorities for every state?

There's a list of reforms that do seem to work. Funding does matter, at least to a point. If you're a low-spending state and you add more funding to education, especially in the highest-need schools, usually you'll get a bump.

Some kind of accountability — if the state's not putting pressure on school districts and schools to focus on student achievement, they're going to focus on everything else but that.

Charter schools, especially in cities, have been shown to be incredibly effective. Make sure that charters schools have the money they need but are also being held accountable for results.

Enthusiasm around the science of reading is a real bright spot right now, something that is getting a lot of attention. You’ve got to get the details right. There have been state mandates to teach reading according to the science, but you’ve also got to invest in curriculum materials and professional development and interventions for kids that are struggling.

What changes could a science of reading approach bring?

We’ve had kids get all the way to high school, and their teachers would realize that they were just looking at the first letter and trying to take a guess at what the word was based on the first letter.

(Fordham Institute)

I'm optimistic that this effort is going to make a difference, but we have got to stick with it. There are going to be places where they say they're doing the science of reading, but don't invest in new materials or really training the teachers, and then we're going to be disappointed that the results aren't very good.

What about voucher programs?

The evidence that we have is much stronger for charter schools than it is for voucher programs and other private school choice programs. You need to have a mechanism for some accountability, and if it turns out they don't really know what they're doing, or they just can't seem to make it work, there's a mechanism for closing the school down.

Without that in the private school choice world, we should expect that there's going to be more variation. There are some great private schools out there, but there are going to be some bad ones too, and, no doubt, some people trying to defraud the public. I certainly support the idea of there being public funding for religious schools, but I wish that that came with some accountability as well.

(Fordham Institute)

In today's politics, especially with so many on the right really opposing any policy that has an explicit racial component, if you can talk about class instead, you're going to gain broader political support.

You can say we need to provide extra resources to kids growing up in poverty, to kids growing up in single-parent families, to kids growing up in dangerous neighborhoods. All of them deserve our help regardless of the color of their skin if they're growing up in those difficult circumstances.

What would you say to state leaders about keeping the focus on education as they navigate fast-moving federal policy changes?

(Fordham Institute)

Every generation, governors and legislators figure out that everything they want to do as a state depends on having a well-educated citizenry. If you want to recruit businesses to your state, if you want to figure out how your people are going to thrive in the AI era, you need people to get a good education.

The argument for investing in education and education reform is as strong as ever. State policymakers should not be satisfied with the state of their schools. We had been doing better not that long ago.

We can be doing better again, but it's going to take leadership for us to get there.