In Brief:

A court case about the inaction of a local Texas police department three years ago, built around legislation enacted 152 years ago to contend with the Ku Klux Klan, has relevance to concerns about 2024 election violence. As its outcome shows, the old law provides a legal foundation that can be used now to push back against harassment and intimidation of voters and election officials.

In October, the police department in San Marcos, Texas, settled a suit filed by passengers in a Biden-Harris campaign bus back in 2020. They had accused the department of violating federal statutes enacted during the Reconstruction era to give teeth to enforcement of the 14th Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

The successful suit is emblematic of a broader effort underway to make sure law enforcement agencies are aware of their responsibilities when it comes to enforcing protections demanded by election codes. “We’re trying to make sure that folks know what’s already available in terms of legal options for protection and defense and prosecution,” says Kathy Boockvar, a former Pennsylvania secretary of state who's now leading an effort to create state-specific guidebooks on election protection.

The Texas suit stems from an incident on Oct. 30, 2020, which was the last day of early voting that year. The San Marcos Police Department received multiple requests to assist Biden-Harris supporters. Their campaign bus was surrounded by backers of Donald Trump who swerved vehicles in their direction or stopped abruptly in front of the bus. The occupants were frightened and concerned for their safety.

Other jurisdictions had provided police escorts to restrain this type of behavior while the bus was within their boundaries. The San Marcos Police Department declined requests to do the same, with consequences that are still reverberating.

The lawsuit against the department cited the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871, which “imposed a duty on all Americans to protect targets of political intimidation and violence in federal elections.” In a statement announcing a settlement with the plaintiffs, the city noted that while it denied “many” allegations in the lawsuit, “the City of San Marcos Police Department’s response did not reflect the department’s high standards for conduct and attention to duty.”

The case could add teeth to efforts underway in many law enforcement departments around the country to strengthen their partnerships with election administrators and to play a vital role as defenders of democracy.

Encouragement, Not a Warning

JoAnna Suriani, counsel at Protect Democracy and co-counsel in the San Marcos case, notes that the provision of the Ku Klux Act used to bring the lawsuit does not apply only to government actors. “It creates legal liability for any individual who is in the position to prevent the harms of election-related violence, but negligently or intentionally fails to do so," she says.

As a term of the settlement, the city will provide training to all department employees regarding core principles, key issues in 21st-century policing, and other topics. Though the city’s statement does not mention it, it will also cover “responding to political violence and intimidation.”

Citing the Ku Klux Klan Act in this case isn’t meant so much as a warning to police but rather encouragement for them to take a greater role in responding to harassment of voters or election officials, Suriani says, including preparing for events before they occur. Training is part of this, she says, and an important achievement from the settlement.

Jurisdictions want to protect their citizens, but they may not know how or when to step in during elections to accomplish this. “We're hopeful that other cities will see this as a model for training their officers proactively so they can be empowered to step in and assist," Suriani says.

The KKK Act was designed to prevent efforts by southern white supremacists attempting to prevent Black Americans from voting. It creates legal liability for those using threats or intimidation to prevent others from engaging in activities related to elections. Last year, it was used to successfully prosecute two operatives who targeted Black neighborhoods with robocalls designed to intimidate them and make them afraid to use mail-in ballots.

Tammy Patrick, CEO of programs at the National Association of Election Administrators, does not see it as a good sign that laws from the turbulent Reconstruction period are proving to be well-suited to this moment. “I don’t think that’s a good indication of where we sit as a country," she says. "I think we need to all take a moment and reflect on what exactly that’s saying.”

(Library of Congress)

A Win for Democracy

Boockvar, who served as secretary of state for Pennsylvania during the 2020 elections, knows more than most about living through election intimidation. She moved her family to another township because of threats. There was a sheriff’s car in the driveway at the new location and patrols in the neighborhood. She didn’t stay alone in her apartment in Harrisburg. At one point, her family left the home where they had relocated to live in undisclosed locations.

“It was a lot, but I feel incredibly fortunate to have had that support of law enforcement at every level who made me, and my family, feel as safe as we could under the circumstances,” she says.

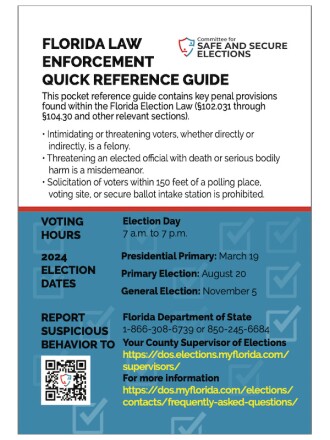

A lawyer by training, Boockvar now works as a consultant on election law and security. As a member of the Committee on Safe and Secure Elections (CSSE), she’s leading its effort to create state-by-state pocket guides for law enforcement to inform them about enforceable crimes in their election codes.

“There were things that I did not realize were on the books in Pennsylvania until I started researching the Pennsylvania pocket guide, prohibiting threatening violence to election officers or interrupting the execution of elections.”

(Athena Strategies)

The guides were conceived primarily as a tool for law enforcement, but it’s becoming clear that they are just as valuable for election officials. Better understanding of when behavior crosses legal lines can improve their conversations with local police about election safety and security.

The research will make it possible for other stakeholders to discover gaps in election law, or figure out approaches to problems such as dissemination of personally identifiable information, by seeing what other states have enacted. Minnesota, Nevada and New Mexico have all recently expanded statutes related to elections, Boockvar says. “There are some good models for states to use," she says.

Boockvar would be happier if these kinds of laws were unnecessary, but has been encouraged by strong interest in the guides, and the interest other organizations are showing in helping make them complete. Law enforcement and election officials share a commitment to protecting their communities. Cross-training that helps them leverage existing election statutes is a win for democracy, Boockvar says.

The Constitution Spells It Out

Over a career spanning decades, Charles Ramsey served as both chief of police in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia’s police commissioner, as well as co-chair of the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing during the Obama administration. The events that led to the lawsuit against the San Marcos police are a departure from past behavior, Ramsey says. “I’ve been in policing for five decades,” he says. “Elections came and went, but we didn’t really deal with the level of threats that we see today.”

(CSSE)

It’s important for law enforcement to work with the community so that officers understand their role in keeping elections free, safe and fair, he says. Some might find the presence of police at a polling place reassuring, but others could experience it as intimidation.

Ramsey recognizes the value of training officers in local election codes or making them aware of federal statues such as the Ku Klux Klan Act. When officers take their oath of office, they swear to protect the constitutional rights of their fellow Americans.

“You don’t need a law to tell police officers that they have to take action,” he says. “There’s no excuse for failing to take action when someone is under assault — that’s your job. Do your job.”

Related Articles