Freedom Caucuses Aren’t Just for Congress Anymore: Last year, Missouri’s Legislature had one of its least productive sessions in decades. So far, this year isn’t shaping up to be much better. Much of the holdup in 2022 was due to filibusters and other procedural maneuvers launched by a group known as the Conservative Caucus. This year, far-right senators are still making life difficult for chamber leaders, now under the banner of the Freedom Caucus.

Last week, an 11-hour session, gummed up by fresh procedural delays, forced the leadership to give up its attempt to confirm more than two dozen appointments made by GOP Gov. Mike Parson. “This is, unequivocally, without a doubt, the worst show of bad faith, or the biggest show of bad faith, I have ever seen in my life,” complained state Senate President Pro Tem Caleb Rowden.

On Tuesday, Rowden stripped four senators of their committee chairs, while also cutting their office budgets and relegating them to distant parking spaces. In response, members of the caucus launched another filibuster, with one proposing a new rule that would allow offended senators to challenge each other to a duel. "The duel shall take place in the well of the Senate at the hour of high noon on the date agreed to by the parties to the duel."

So at least there's still some civility left when it comes to dueling.

Rowden, who is a Republican, is not alone in his frustration. In Congress, the House Freedom Caucus ousted GOP Speaker Kevin McCarthy last October. Things haven’t reached quite that point at the state level, but many chamber leaders, including conservative Republicans, are having to deal with their own confrontational freedom caucuses. In many states now, there is open factionalism between the Republicans running the chambers and the ultra-conservatives who complain the legislative agenda doesn’t go far right enough on issues ranging from transportation to tax cuts and transgender health care.

Last year, the Freedom Caucus in the South Carolina House won a federal lawsuit challenging restrictions leaders sought to impose on its ability to back primary challenges. This year, the caucus has already made lots of noise about a proposal to limit floor amendments, which members view as an attempt to muzzle them. "RINO 'Republicans' are attempting to bring Nancy Pelosi-style rules to the South Carolina House with the sole purpose of silencing conservatives," groused R.J. May, the caucus vice chair.

There have always been factions within legislative parties, with Republicans in several states forming Tea Party caucuses a decade or so ago. At the beginning of the Trump presidency, only a handful of states saw the formation of freedom caucuses. More than a dozen have started up since 2021, however, driven by the State Freedom Caucus Network and the Conservative Partnership Institute, which hosted a big gala as a recruiting effort at the end of that year. Both groups are associated with Mark Meadows, a former chair of the U.S. House Freedom Caucus and former White House chief of staff to Donald Trump. “These are people who see themselves as party shapers, or party builders.” says Matthew Green, a Catholic University political scientist and co-author of a forthcoming study of state freedom caucuses.

Affiliation with the national network not only gives state-level caucuses a brand and a playbook, but comes with staff support as well. That’s always a plus for legislators, most of whom have little to no staff of their own. “It is a concrete example of the nationalization of politics,” Green says. “They can be accused of parroting national talking points, not reflecting needs of their constituents.”

The influence of each caucus varies by state. In blue states such as Illinois, they can make noise but remain fairly toothless as a minority within a minority. In Arizona, where Republicans hold narrow majorities in both chambers, the caucus makes up a key voting bloc. Most dramatically, they’ve blocked some key appointments made by Democratic Gov. Katie Hobbs.

In every state where they appear, freedom caucuses cause headaches for the so-called establishment Republicans in charge. Last year, Wyoming House Speaker Albert Sommers made his frustrations public, publishing an op-ed accusing the Freedom Caucus in his chamber of inciting fear and stoking anger.

In response to the Freedom Caucus, other Republicans formed what they called the Wyoming Caucus, claiming the mantle of best representing the interests of people in the state. “The most striking feature of the House Freedom Caucus this last session was they were voting in lockstep in accordance with text-message instructions that they would receive,” said GOP state Rep. Clark Stith. “The interesting effect of that is that it, to some extent, forced the remaining members of the House to become slightly more organized.”

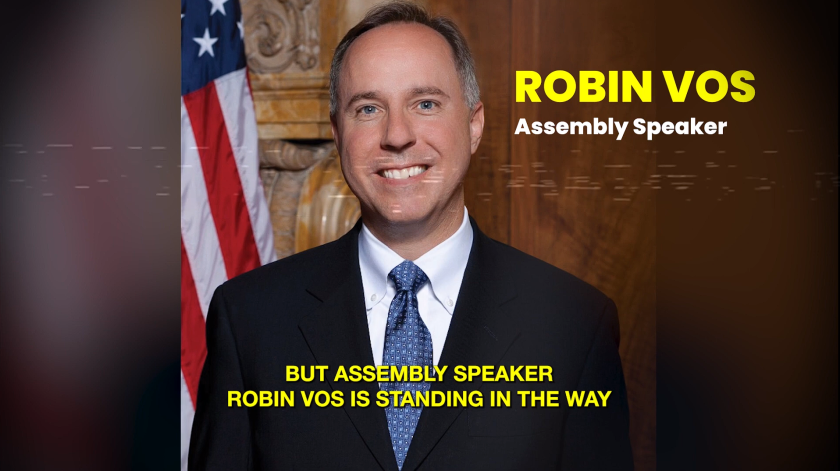

Like a lot of Republicans, Vos went out of his way to entertain complaints that the 2020 election was either marred or stolen outright from Donald Trump. Vos hired Michael Gableman, a former state supreme court justice, to launch an investigation into voting in the state, which was one of the closest in that year’s election. Gableman uncovered no evidence of fraud but called for the state’s certification of the election to be withdrawn anyway. Vos fired him, calling him an “embarrassment.” Getting off the election fraud bandwagon cost Vos. The speaker narrowly survived a “Toss Vos” primary challenge backed by Trump (and Gableman) in 2022, taking just 51 percent of the vote.

Vos notes that Wisconsin has made a number of efforts to bolster election security since 2020, including a court ban on ballot drop boxes and a new law on the processing of absentee ballots. The Legislature has sent voters an amendment, to be decided in April, which would bar private donations for election administration. "Let's focus on the future and say, we've made progress … as opposed to being obsessed with the past, where it does nobody any good,” Vos said last month.

But complaints about the 2020 election in Wisconsin never seem to fade away entirely. In September, state senators voted to fire Meagan Wolfe, the top election official in the state, over her handling of that election. They didn’t have the authority to do so. Now, a handful of Assembly Republicans are seeking to impeach her. Vos says he favors her removal, but doesn’t support impeachment.

Now Vos is facing a recall attempt. It’s not likely to succeed, but it’s a reminder for Vos that he may never be able to put this issue behind him. "This recall is a waste of time, resources and effort,” Vos says. “The people involved cannot seem to get over any election in which their preferred candidate doesn't win.”

The reason is staggered terms. In 20 states, Senate elections are staggered, meaning elections are held for half the chamber during each two-year cycle. When redistricting happens, some senators are assigned constituents in their new districts, who then have to wait for years to vote for or against them. “Eleven percent of Coloradans will go six years between Senate elections,” complains Daily Kos, a liberal website. “This could violate the Constitution's ‘one person, one vote’ guarantee.”

It does sound bad. Eight states solve this problem by running two-four-four Senate cycles, meaning senators have to face voters in their new districts right away, before resuming four-year terms. In some states, senators are randomly assigned to two- or four-year terms after redistricting. Twelve other states stick with two-year Senate terms all the time.

But how big a problem is the delay? In a study from 2016, Princeton University political scientist Rocío Titiunik looked at the behavior of senators in states where some got two-year terms and others got four years. She found that the short-timers “abstain more often” and “introduce fewer bills.” They also raise and spend a lot more campaign money.

It sounds like they’re worried about re-election. Which is kind of the point. Voters, after all, should have the final say over who represents them.

Previous Editions

-

The GOP has usurped Democrats among working class voters, increasingly including those who aren't white. Also: Several states will have new maps due to redistricting court fights, while Joe Arpaio decides to run for another office at 91.

-

The Michigan GOP is not the only state party with a treasury running dry. Meanwhile, in New Jersey, the fix is in for the governor's race. Plus, a reflection of Sandra Day O'Connor, legislator.

-

Democrat Andy Beshear wins re-election in a state that otherwise elects only Republicans to statewide office, the particular challenges facing Black women mayors and other election fallout.

-

Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear looks more likely than not to win re-election. Meanwhile, Louisiana Democrats failed to field candidates in many districts for state House and Senate, Oklahoma's Republican attorney general files a lawsuit to block a publicly funded religious charter school and more.