For Benjamin Wade, it was a sad homecoming. A couple of years ago, he graduated from Fontbonne University, a small Catholic school in St. Louis. With the campus about to close, he drove over on an April morning to take a last look around. It was already empty. When a cluster of five students walked out of the science building together at the stroke of noon, it was as crowded as the quad got all day. “I had so many good memories here,” Wade says. “It’s really sad. There used to be a lot more students, especially during this time of year.”

Fontbonne made some mistakes, but its demise was mainly due to forces outside its control. Basically, it ran out of students, with enrollment plunging from about 2,000 a decade ago to fewer than 900 by the time it announced its closure last year. This is a challenge for colleges and universities around the region and indeed around the country.

Back in 1980, the St. Louis metropolitan region was home to 215,000 children under the age of 5. Now, it’s down to 149,000, according to J.S. Onesimo Sandoval, a demographer at St. Louis University. Over the next decade or so, their numbers will drop to 100,000. “There are several universities that I don’t think will be around in 2040 because we live in a state that just has fewer children,” he says.

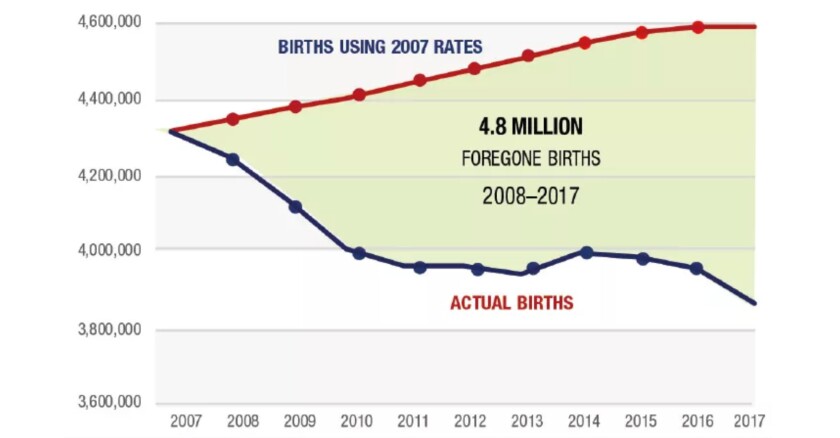

K.M. Johnson, University of New Hampshire

The enrollment cliff is far from the only challenge higher education is facing. The budget and tax package passed by the U.S. House in May included more than $351 billion worth of cuts to education and workforce programs, with additional cuts to higher education included in President Donald Trump’s proposed budget for next year. Not all these changes may survive the congressional process, but it’s clear that aid to institutions and financial help for students are in for substantial and possibly perilous cuts.

That’s on top of the billions in university research grants that Trump has sought to eliminate. Some of that money has been preserved so far by the courts, but this is not going to be an administration that’s supportive of higher ed. The president has made a particular target of Harvard University, seeking to end all federal funding for the school, but he’s gone after other campuses as well. “Universities should continue to be able to do research as long as they’re abiding by the laws and in sync, I think, with the administration and what the administration is trying to accomplish,” Education Secretary Linda McMahon said in May.

Alan Greenblatt

Because other federal cuts, notably those to Medicaid, will put pressure on state budgets, public college and university presidents are worried that their own states will cut their spending. During budget downturns, higher ed is always a primary target for state lawmakers since tuition gives schools a separate source of revenue. Red state lawmakers have also challenged academic freedom, limiting teaching of race and gender while requiring instruction of certain core civics documents.

Increased tuition costs for students will make life more difficult for recruiters already facing a dwindling pool of potential applicants. “It means lower enrollment than they had been anticipating even with the demographic challenges,” says Robert Shireman, a former Education Department official now with The Century Foundation.

Public ambivalence toward higher education is also a factor. People in higher education believe that even members of the public who tell pollsters they hate universities still support their local schools. They may have gone there or root for the sports teams or recognize how important they are to the local economy. Policymakers and the media may take Harvard and its peers as emblematic of higher ed, but the reality is that the Ivies and other top schools educate a tiny proportion of students, far less than state universities and community colleges. “If you are angry at 10 institutions, don’t penalize 500 to get your message to those 10,” says Charles Welch, president of the American Association of State Colleges and Universities (AASCU).

Alan Greenblatt

“For those institutions that are willing to change and willing to adapt and willing to be different, they can have a brighter future,” Welch says. “For those that resist — and higher ed historically has been very resistant to change — I definitely think it’s murky and the future is challenging.”

Because of its importance both to individual prospects and the economy as a whole, higher ed has historically had motherhood and apple pie-type support, dating back from the land-grant colleges of the Civil War period through Dwight D. Eisenhower’s expansion of federal support as part of a national security strategy during the Cold War.

But there has also been plenty of grumbling. Democrats have tended to get angry in recent times over rising tuition and the resulting explosion in student debt. The discount rate, or the difference between the advertised sticker price and what students actually pay for tuition, is approaching 60 percent at private universities. “The national graduation rate is only 60 to 65 percent, and for underrepresented students it’s much lower,” says Brian Rosenberg, former president of Macalester College in Minnesota. “Politically, the economic model is not working well — you shouldn’t have a business where half your students aren’t finishing.”

Alan Greenblatt

Support for higher ed was not a partisan issue until recently. A decade ago, a majority of Republicans had confidence in higher ed, but now a majority do not, according to Gallup polling. Support among Democrats has also declined, but not as dramatically. (This split is also reflected in voting, with Democrats carrying majorities of college-educated voters but losing badly among those who lack degrees.) “The way regular people feel about the cost of college, Republicans have marshaled that energy and then channeled it,” says Sara Goldrick-Rab, author of Paying the Price: College Costs, Financial Aid, and the Betrayal of the American Dream. “‘The colleges simply don’t care about you and they don’t represent regular people.’”

As public opinion has shifted over the past decade, higher ed’s response has been either weak or nonexistent. People in higher ed have insisted that college, no matter how expensive, still pays off in the long run. They’ve also been a bit smug and defensive. The same politicians complaining about higher ed, they’ll say, hold a string of degrees and send their own children to the best schools.

But at this point, people in higher ed have been forced to recognize that they have a damaging public relations problem. “The way the public and policymakers value higher education is the single biggest threat,” says Welch, the AASCU president. “If they have a low valuation of a college degree or a college experience, it disincentivizes attendance and enrollment and it disincentivizes government support.”

The nation’s student body has already changed. There are still 18-year-olds checking into dorms, but the average age on campus has gotten higher, at just over 26. More than 20 percent of undergraduates have children of their own. “Schools have a revenue problem that they’re not going to solve on the backs of 18- to 22-year-olds,” Rosenberg says. “You’re seeing more schools trying to figure out ways to serve the adult learner audience, whether it’s through mid-career training, online classes or training certificates, because you have one market that’s shrinking and another market that’s a lot bigger.”

Alan Greenblatt

Some schools are taking an approach that seems blindingly obvious but is all too seldom a priority: focusing on student success. Rather than expanding research or recruiting high school high achievers, for example, Northern Arizona University in recent years has loosened admission requirements to allow in practically any state resident, offering free tuition to many students and ramping up outreach both to underserved populations and potential employers to set students up with the skills they need to land jobs.

David Kidd

There’s also a lot of talk about three-year degrees that would allow engineering students, say, to skip out on humanities classes and take only career-essential courses. No matter the budget realities, however, there’s always a lot of internal pressure on campus against shutting down art history or language programs. Academics warn against marching too much farther down the vocational training road.

What sounds like job-ready training may turn out to be shortsighted. A few years ago, all the talk was about convincing humanities students to switch to 12-week coding camps. Today, thanks to artificial intelligence, computers can do a lot of their own basic coding. “Employers now are at the point where they’re like, ‘We actually value a liberal arts education, because it teaches you problem solving, how to write well, and reasoning skills that are actually what we need,’” says Jared Bass, senior vice president for education at the Center for American Progress, a progressive think tank. “I just worry that we are going to train people in such a way where they are good for this one thing and not able to have a multitude of experiences that offers them a multitude of options.”

One of the first things colleges struggling with their budgets are prone to cut is support programs, says Goldrick-Rab. The combination of less help for first-generation college students, along with declining student aid, will mean a steady drop in retention rates. More students are going to leave campus with debt but no degrees.

Alan Greenblatt

In Macomb, Ill., 150 miles north of St. Louis, the city’s population has fallen by a quarter since 2010 as enrollment at Western Illinois University has dropped by half. In May, the Penn State system announced it will close seven campuses in 2027. “In Pennsylvania right now, we have 18 counties that don’t have a single college left in them,” Goldrick-Rab says. “Are we surprised that the people of Pennsylvania don’t support higher ed?”