She should have been resting, spending time with her family, but instead, she was battling insurance companies for money she had already earned.

“It’s a torrential nightmare,” Stone said. “A dog and pony show.”

Stone, a psychiatric nurse practitioner and U.S. Air Force veteran, opened her psychiatric practice in 2023 and signed up to serve Medicaid patients — those often left behind in Illinois’ health care system. But she quickly learned that treating them wasn’t the hard part. Getting paid for that treatment was.

Each week, she spends hours — sometimes entire weekends — writing emails, compiling evidence, and escalating complaints about delayed or denied reimbursements. She’s taken her concerns straight to the top, firing off messages to CEOs of Medicaid Managed Care Organizations, or MCOs — the entities in charge of reimbursing providers for Medicaid claims — and even the director of the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, or HFS. The responses, when they come, often offer little relief. She’s been asked to work through her appointed representative and stop contacting higher-ups. She refuses.

Providers like Stone say Illinois’ Medicaid system is in crisis.

“This isn’t just oversight failure, it’s a betrayal of public trust,” she said.

The state relies on these private insurance companies to manage Medicaid payments, but when delays extend too long or denials become too frequent, small clinics and safety net hospitals end up in financial turmoil. Meanwhile, MCOs have seen significant increases in profits — one reported an increase of over $2 billion in the last two years. Yet, they are regularly failing to meet the metrics for quality of care established by the state.

Conservative estimates based on limited data from the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services suggest that claims have been denied at rates as high as 17.5 percent over the years. That estimate does not include the average of 59 percent of appealed denials that are later overturned, but providers say overturned denials contribute to the delays in reimbursement that are causing them financial distress. Many are drowning in unpaid claims, forced to take on billing battles instead of patient care. Some simply stop accepting Medicaid altogether, leading to significant declines in the number of Medicaid providers in the state where nearly one in three residents rely on the program.

But change may be on the horizon.

The five MCOs currently overseeing Illinois’ Medicaid system were awarded state contracts in 2018.

The state will soon begin accepting proposals for new contracts, set to take effect Jan 1, 2027. For providers like Stone, the upcoming shake-up raises urgent questions: Will the next round of contracts fix the system’s failures? Or will the same issues persist, leaving providers — and their patients — fighting for care?

For now, Stone refuses to turn patients away. “We weren’t going to make them suffer,” she said. “I’m gonna fight.”

Denials and Delays

Over the years, reimbursement delays and denials have made it nearly impossible for Debra Lowrance to continue caring for the state’s most vulnerable mothers. In 2018, she opened Labor of Love Midwifery and Women’s Health in Robinson, Illinois, offering prenatal, birth and postpartum care. As one of a handful of Certified Nurse Midwives, or CNMs, providing home births in southern Illinois, Lowrance says she is in high demand, covering areas up to three hours away by car, including southern Indiana, to serve patients.

Each year, she is forced to take on fewer Medicaid patients to maintain financial stability. In 2019, Medicaid patients made up 21 percent of her practice. Last year, that number was just 8 percent.

“When we had some patients that were still straight Medicaid, I could get some reimbursement from them. Of course, the rate is awful, but at least it’s something,” Lowrance said. “But then when they started divvying up to the MCOs, that’s when I really started having trouble.”

That shift began in 2017, when former Gov. Bruce Rauner started to revamp Illinois’ use of Medicaid managed care when he chose to consolidate the system into seven MCOs.

Over the years, Lowrance has spent countless hours navigating denials and appeal processes, only to lose out on payment entirely.

“I ended up hiring an outside biller that helps me,” she said. “I’ll get handfuls of denials on the same patient over and over and over. And we’re checking things and we know we’re doing it right, but they just keep denying, denying and denying.”

Like Stone, she’s frustrated with the lack of transparency and accountability in the system.

In response to a public records request for data or reports showing MCO reimbursement delays between 2019 and 2024, The Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services said it “doesn’t broadly track this data.” However, the agency does release quarterly reports on institutional hospital claims, which show that MCOs have denied and rejected claims at rates ranging from 8 percent to 17.5 percent since 2018.

The data does not count an initial denial or subsequent denials as a denial if that claim was eventually accepted and paid. Even when overturned, these initial denials can result in delayed reimbursements. Some hospitals and providers do count the initial denials they receive and they report much higher denial rates for their practices — some report a 20 percent rate, and others a rate as high as 60 percent.

Under their current contracts with the state, MCOs are required to promptly reimburse providers who treat Medicaid patients. State rules mandate that MCOs pay 90 percent of uncontested claims within 30 days and 99 percent within 90 days.

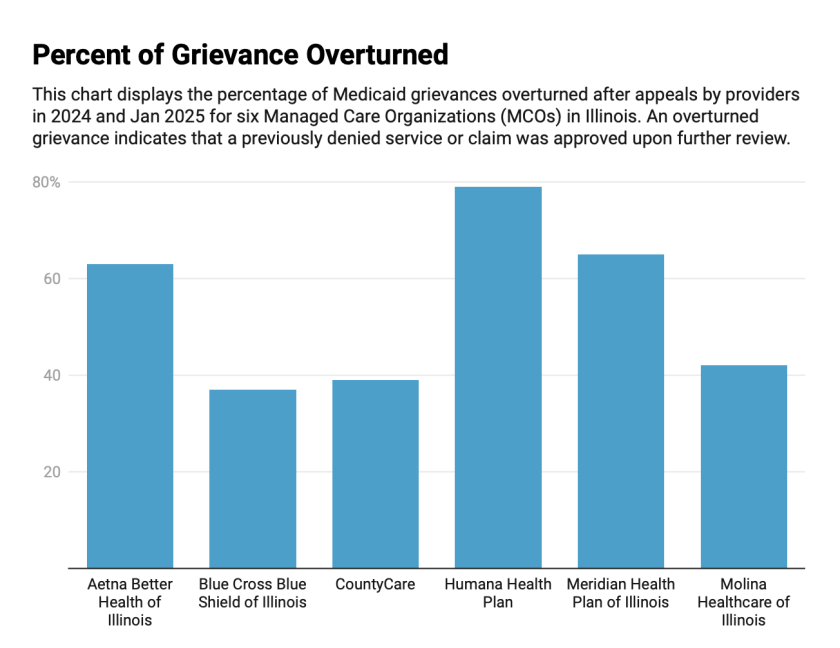

Providers say the reasons given for denials are inaccurate or arbitrary, causing unnecessary delays. That concern is backed by data showing that, on average, 59 percent of formal grievances filed with MCOs in Illinois are overturned after being appealed by providers.

(Illinois Healthcare and Family Services)

In some cases, providers who can’t bear the financial burden of delayed payments stop accepting Medicaid patients altogether.

The number of Illinois hospital-based providers accepting Medicaid patients has declined by approximately 27 percent in recent years — falling from 1,473 in 2018 to just 1,073 in 2024, according to data obtained by the Illinois Answers Project.

(Illinois Healthcare and Family Services)

In a federal lawsuit, Saint Anthony Hospital, a safety-net facility on Chicago’s West Side, alleged that chronic underpayments from MCOs nearly forced it to shut down in 2020. Court filings show the hospital’s available cash reserves fell from $20 million in 2015 — enough to operate for 72 days — to just $500,000 in 2019, barely covering two days of expenses. The lawsuit alleges that denials and delays by MCOs are the cause. The case was recently dismissed following a Court of Appeals decision. The hospital intends to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court.

“Saint Anthony remains committed to providing high quality medical care to all its patients. It also remains committed to support that care by vigorously pursuing its legal right to prompt and transparent payments,” wrote the hospital’s attorney Mike Shakman in an emailed statement.

The complaint states that MCOs often deny or delay claims without justification, sometimes for technical errors that are unrelated to the care provided. In one example, the hospital says an MCO denied a $92,000 claim because the patient’s name on a consent form was computer printed instead handwritten. Another denied a pediatric claim because a birth weight was not included, but the hospital argues the birth weight wasn’t relevant to the service.

In court, the hospital argued that because most MCOs are for-profit, they have built-in incentives to deny or delay reimbursements. The state pays MCOs a fixed amount per Medicaid patient, regardless of how much care that patient actually receives — so the less the MCO spends on care, the more it keeps.

The Affordable Care Act requires insurance companies to spend at least 80 percent or 85 percent of premium dollars on medical care.

The hospital also points to the erosion of HFS oversight. Despite federal and state laws requiring states to monitor MCOs for timely and fair payments, the complaint says HFS has failed to publish timely performance reports, audit claim denials, or track whether MCOs are applying state-mandated Medicaid payment enhancements meant to support safety-net hospitals. Even when providers raise red flags — as Saint Anthony did in multiple meetings with the agency — HFS has repeatedly failed to take action, according to the lawsuit.

In an emailed statement, HFS said it encourages providers to seek to enforce their rights under their contracts. “HFS can utilize multiple enforcement mechanisms to hold the health plans accountable: corrective action plans, financial sanctions and placing a hold on the auto-assignment of members to a plan. The Department has and will continue to use these enforcement mechanisms when necessary,” a spokesperson for the agency wrote.

The state has acknowledged the ramifications of reimbursement delays.

In 2019, former Illinois Medicaid Director Doug Elwell warned CountyCare — the only government-owned, provider-led MCO in Illinois, operated by Cook County Health — that providers were waiting up to nine months for payment. “We doubt all providers will make it,” he wrote in an email, urging the county or state to intervene before critical safety-net hospitals and nursing homes were forced to shut their doors.

Delays in provider payments can also stem not from the managed care organizations themselves, but from the state, according to Elwell. In a 2020 deposition, Elwell testified that when the state falls behind on its monthly payments to MCOs — a common occurrence — it can paralyze the system.

At another safety net hospital, Franciscan Health Olympia Fields, Chief Financial Officer Frank McHugh said that delayed and denied reimbursements from MCOs are a major strain on the hospital’s bottom line.

(Franciscan Health Olympia Fields)

“We’ve had to add an additional physician advisor to help with denials,” McHugh said. “We have additional people in our business office and revenue cycle team. It puts a strain on our care management staff.”

McHugh said the financial pressure has prompted internal conversations about whether Franciscan should consider legal action similar to the lawsuit filed by Saint Anthony Hospital over Medicaid reimbursement practices.

For smaller practices like Stone’s New Leaf Behavioral Health, a couple of denied claims makes a huge difference. Last year, Stone contacted the state concerning 100 claims with denied or incorrect reimbursements at once.

“I have others who work for me,” she said. “It’s not just about ‘hey want my money…’ A lot of times I may not pay myself because I’m going to take care of them first.”

But reimbursement issues are just one piece of a larger problem. MCOs are supposed to coordinate care by ensuring access to primary care providers, arranging transportation, and incentivizing timely visits. When they fail to do so, McHugh said, patients often end up in the emergency room instead — shifting the cost of care onto providers that are already financially vulnerable.

Rising Profits, Declining Performance

Medicaid payments haven’t always been so hard to get. Prior to 2018, Saint Anthony Hospital said they received more consistent and adequate payments directly from the state — a model they say offered greater financial stability.

The managed care model, which originated in the 1960s and 70s, is designed to control costs and incentivize efficient care — but it also means that if the cost of services exceeds the payment, the MCO absorbs the loss.

During Rauner’s administration, in August 2017, HFS awarded new contracts to seven MCOs, expanding managed care coverage from 30 counties to all 102 across the state. Valued at $63 billion, the contracts marked the launch of HealthChoice Illinois — the largest procurement in the state’s history.

Since then, spending on managed care has skyrocketed. In fiscal year 2010, HFS spent just $251 million on MCOs. By 2023, that number had ballooned to nearly $22 billion and Illinois ranked sixth in the country for MCO-related spending. Today roughly four out of every five Medicaid enrollees are covered by an MCO.

Despite this dramatic increase in investment, providers and patients say they’re not seeing the benefits. Some argue that the sheer volume of spending has done little to improve care access or streamline reimbursement, and instead has created a system where insurers profit by withholding payment. For patients, the promised efficiencies of managed care — better coordination, more timely services, and broader provider networks — often fall flat. The disconnect between rising investment in MCOs and worsening outcomes for patients and providers has fueled calls for stronger oversight and reform.

An Illinois Answers analysis examined several years of financial statements filed with the Illinois Department of Insurance.

Both revenues and expenses have increased by roughly a billion dollars between 2020 and 2024. Records show that while there is some high variability in annual profits in the last few years, Illinois MCOs are typically profiting hundreds of millions a year.

(Illinois Department of Insurance and Illinois Healthcare and Family Services)

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois — part of the larger Blue Cross Blue Shield network — reported $1.4 billion in net income that year, though that figure includes results from four other states and isn’t directly comparable.

Corporate profits for some MCO parent companies have also increased in recent years, in part driven by billions in taxpayer-funded premiums. Centene Corporation, which owns Meridian Health Plan of Illinois, reported $1.2 billion in overall corporate profits in 2022, rising to $3.3 billionby 2024.

(Rachel Heimann Mercader)

The state’s Medical Loss Ratio reports offer a partial window into MCO finances by showing how much of each premium dollar from the state is spent on patient care — and how much is left over.

According to these state reports, Illinois Medicaid insurers have been keeping more money than ever before. In 2022, major players like Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois and Meridian Health Plan of Illinois retained three to eight times more than they did in 2018.

Overall, the number of Medicaid patients enrolled in Illinois MCOs increased by roughly 26 percent between 2018 and 2022.

While these corporations are seeing financial gains, they are falling short on key performance metrics set by the state for quality patient care. HFS publishes quarterly reports tracking MCO performance, including the timeliness of health assessments.

Between the first quarter of 2020 and the last quarter of 2023, only one of Illinois’ five main MCOs met the target for completing health risk assessments or screenings for at least 70 percent of new enrollees within 60 days. That exception was Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, which hit the benchmark only once — in the third quarter of 2022.

For the rest of the reporting period, all five Illinois MCOs — Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois, Meridian Health Plan of Illinois, Aetna Better Health of Illinois, Molina Healthcare of Illinois and Humana — consistently fell short, often by 20 to 30 percentage points or more.

This pattern extends to another critical metric focused on high-risk enrollees. Despite state requirements that 60 percent of high-risk enrollees receive an individualized care plan within 90 days, most MCOs in Illinois consistently fell short of this benchmark. The data shows that, quarter after quarter, four out of five plans failed to meet the threshold — leaving some of the state’s most vulnerable patients without timely, coordinated care.

Only Aetna Better Health of Illinois consistently met the state’s 60 percent threshold, while other insurers — including Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois and Meridian Health Plan of Illinois — remained well below the threshold, with some rates dipping as low as 13 percent.

Aetna Better Health of Illinois, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois and Meridian Health Plan of Illinois did not respond to requests for comment.

“We are actively working to streamline our reimbursement processes and improve key performance measures while continuing to build a Medicaid program that providers trust and members rely on,” Alexandra Normington, chief communications officer for CountyCare told the Illinois Answers Project.

In an emailed statement, HFS said its staff discusses permanence metrics with MCOs during their quarterly business reviews. “HFS’ Bureau of Managed Care is in the process of updating the metrics used for these reports, including care coordination, and moving away using MCO-reported data, where possible, to improve data integrity,” a spokesperson for the agency wrote.

Patients Can’t Find Care

Medicaid enrollment in Illinois grew from about 2.9 million in 2019 to nearly 3.9 million in 2023, partially due to pandemic-era policies that paused eligibility checks and allowed people to remain enrolled regardless of changes in income or status.

In 2024, both enrollment and provider participation fell. Enrollment declined by about 660,000 people at the same time as redeterminations after the pandemic-era coverage rules ended, and the number of participating providers dropped by nearly 60,000 — a 19 percent decrease, wiping out several years of growth.

Providers say the decline may be tied to low reimbursement rates, administrative burdens, and growing frustrations with managed care organizations.

For patients the decline in providers can mean long waits for care or traveling long distances to find a provider.

When Finn Bradley went on Medicaid in 2022, they had to give up their therapist. The 29-year-old Chicagoan, who identifies as queer, had been seeing someone they trusted — a provider who understood their background and needs. But switching to a Medicaid plan meant starting over in a system that was already hard to navigate.

They chose Aetna Better Health, but finding a new therapist, one who accepted Medicaid, took months. The therapist they had at the time, understanding the delay ahead, offered discounted intermediary sessions. But there was still a gap in care and it came at a cost to both Bradley’s mental and financial health.

“Having support in that way is pretty important for me, and not having it — I can feel a little bit lost and have a harder time,” Bradley said.

Bradley isn’t the only one.

A December 2024 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General found that the country lacks enough behavioral health providers who accept Medicaid to meet current demand.

In 2021, fewer than half of those with a mental illness received timely care, according to the report. The Inspector General urged states to boost provider participation by easing administrative burdens and reassessing reimbursement rates for behavioral health services.

For many Medicaid patients, delays in care as they search for a provider aren’t just inconvenient — they’re dangerous, said Nadeen Israel, senior vice president of policy and advocacy at AIDS Foundation Chicago.

Cornelia (Cye-Cye) Simms, 59, lives on Chicago’s South Side and said it can take her up to an hour and a half by CTA to reach a Medicaid mental health provider — most of which are concentrated on the North Side. When she recently needed heart testing, she couldn’t find a provider who accepted her coverage and ended up paying out of pocket at Northwestern Medicine.

“I was weighing whether I should eat or (make a monthly payment),” she said.

The financial stress is compounded by the mental toll.

“For folks who already qualify for the Medicaid program, you have to be in or near poverty,” Israel said. “You’re low income, so you’re already dealing with a lot just to survive, just kind of day to day — whether it’s rent, housing, food, family, child care, school, your job. (Not having mental health care) adds another… unsustainable barrier to accessing basic care.”

Bradley said the emotional toll of having to start from scratch in finding someone who truly understood them was particularly impactful.

“When therapy is a specialized care and you’re looking for somebody who understands you in various ways, the relationship between the therapist and the client is really important. So you want to trust them and not just find the first person who accepts your insurance,” they said. “Unfortunately, that is what a lot of people on Medicaid feel like they have to do.”

Attempts at Accountability

As delays and denials mount, the system designed to hold MCOs accountable has been slow to act.

In 2021, the Illinois General Assembly established the Medicaid Managed Care Oversight Commission to monitor and evaluate the program’s effectiveness. The governor-appointed commission was supposed to start submitting findings and recommendations to the General Assembly in January 2022 on a quarterly basis. The commission did not meet for the first time until 2024.

“Really nothing has occurred,” said commission member Gerald DeLoss, CEO of Illinois Association for Behavioral Health.

HFS, which assists in staffing the commission, did not directly address questions about why the commission did not meet until 2024, but said “it is the commission’s co-chairs who are empowered to set the timing of meetings.” Emails obtained by Illinois Answers show that HFS staff set up the meetings that were held in 2024.

“HFS values the commission’s input about how to continue to improve Illinois Medicaid managed care,” a spokesperson for the agency wrote in an email.

Delozz’ organization represents community-based mental health and substance abuse providers who serve Medicaid patients, and communicates with MCOs and advocates for compliance with state regulations. But progress towards addressing the issue of reimbursement denials, he said, has been limited.

“It’s almost humorous, in an ironic way,” he said. “That we have a field (mental health care) that is underpaid, underfunded, that looks to trade associations like ours and others to help them to understand the laws and comply with the law.”

“And then you have a managed care field that is extremely well funded, extremely well organized – (a) number of lawyers, (a) number of regulatory people and policy analysts – and they can’t keep up to date on the laws in our state.”

Republican Senator Dave Syverson, who is also a member of the commission, said he is also hearing about how denials and delays are impacting providers and hospitals.

“When there’s no logical reason, and the carrier has to go back and appeal it and submit more data, it just takes a lot of extra time and work, which delays getting the payment to the provider,” he said. He added that he hopes changes in the new MCO contracts will help the situation.

While providers wait to see if things will change with the new contracts, Paris Ervin, spokesperson for the Illinois Health and Hospital Association, or IHA, says hospitals have poured significant resources into managing what she described as “intentionally obtuse and inconsistent” prior authorization processes, which she says are another way MCOs delay or deny care.

Prior authorization is a process where insurers require providers to obtain approval before delivering certain treatments or services, which can result in delays or outright denials — even when care is medically necessary. These processes, she said, are often designed to boost profits “at a significant cost to patient care.”

In response, IHA partnered with the Illinois General Assembly and Pritzker’s administration to pass legislation aimed at easing the burden of prior approval. The legislation, which was signed into law in July 2024, established new guidelines for prior authorization, including a “gold card” program to streamline approvals for providers with strong track records.

IHA has worked with the HFS and the MCOs to develop administrative rules for implementing these reforms, and a draft of those rules is expected soon.

Still, Ervin said that prior authorization denials and delays remain among the top challenges to providing care to Medicaid patients. “Inappropriate denials negatively impact health care for Medicaid patients,” she said. “Every dollar that is spent on navigating these inconsistent and unfair MCO processes is a dollar that is not available for patient care or community services.”

Looking ahead, IHA has submitted formal recommendations for the state’s next round of MCO contracts. IHA’s proposals include calls for higher reimbursement rates, reduced administrative burdens, better care coordination and stronger requirements for mental health and substance use disorder parity.

HFS told Illinois Answers that starting in early 2024, in preparation for new contracts, the agency sought input from customers, providers and advocates about how MCOs can better serve Medicaid customers and improve quality.

The state’s new Medicaid managed care contracts are expected to be finalized in 2027 — offering what many hope will be a turning point. But until then, providers and patients remain stuck in a system marked by uncertainty, financial strain, and limited accountability.

“As sure as the day is long, I am going to aggressively go after (payment) because I rendered services,” Stone said. “I want to be paid for the work that I do, because it’s not just about me. I have people who work for me, who need their paychecks because they need to take care of their family and their kids and they need to be paid.”

This story first appeared in Capitol News Illinois. Read the original here.