In Brief:

- It’s challenging for incarcerated people to access reading materials. In some prisons, libraries are not reliably open or well-stocked.

- Operations like Quincy, Mass.’ long-running Prison Book Program sends packages of free books to incarcerated people around the country. It often takes months to respond to each request, given the high demand.

- Staying on a prison’s accepted vendor’s list requires constant work, as programs must keep up with each individual facilities’ latest rules and restrictions.

In the basement of a Unitarian Universalist church in Quincy, Mass., a group of volunteers are busy at work. They range from retirees to high school students, and together they hunt among bookshelves or cluster around tables, sliding books into plastic envelopes and preparing to ship them out. In the kitchen, two volunteers sort donated books on a long table, stacking them into piles by genre.

This is the regular Wednesday afternoon meeting of the Prison Book Program, a nearly all-volunteer effort that for decades has sent free books to incarcerated people around the country.

Jails aren’t required to have libraries. And while prisons do have them, they aren’t always well-stocked or frequently open, says Kelly Brotzman, executive director of the Prison Book Program. Prisons that laid off librarians during COVID-19 have been struggling to rehire.

“People are telling us, ‘Oh my gosh, there's one librarian for six facilities in our state, and she's here like two hours a month,’” Brotzman says. It leads to drastically reduced library time — and drastically less access to books — for the incarcerated.

And in prison, books can mean a lot.

“There are a lot of people in prison who look at books as their way of making it out, becoming somebody different, bettering themselves,” says Charlie Rosario, who was released from prison two years ago, after serving 19 years. Rosario is now a program coordinator at the Emerson Prison Initiative and recently joined the Prison Book Program’s board.

The Prison Book Program fulfills requests from about 20,000 incarcerated people a year, sending them packages of three to four books at no cost, with the selections chosen from among mostly donated, and occasionally purchased, books to best fit each person’s written requests.

It’s far from the only program sending free books to incarcerated people, but it’s one of the few national ones, says Joyce Tanner, a volunteer since 1995. Every once in a while, they’ll discover a new program has closed when letters addressed somewhere else start arriving, forwarded to the Prison Book Program.

Getting Books in Prison

It’s remarkably hard to get books in prison.

For one, many incarcerated people don’t have access to the Internet. They need a bookseller to provide paper catalogues from which they can purchase, and to accept payment by paper check. And then there’s the expense; even bargain books can be hard to afford, with incarcerated people earning an average of 13-52 cents per hour of work in 2022.

In an effort to prevent contraband, facilities also forbid family and friends from directly mailing in a book; instead, they must purchase through an approved vendor. That’s a status the Prison Book Program worked hard to obtain at 1,000 facilities in all 50 states and several territories — and often fights to regain anytime it gets cut from a list.

For a growing number of prisons, approved vendor lists no longer include Amazon or Barnes & Noble. That’s likely because the companies started using third-party organizations to ship their books, and are no longer responsible should someone smuggle in contraband among the items, Rosario says.

Jule Pattison-Gordon

More recently, tablets have come into some prisons. While some facilities reportedly charge per book or per minute of reading, Rosario’s prison provided free access to a selection of 100-150 titles. But they weren’t as widely used as he’d expected.

“A lot of guys on the inside, they don't really access those, because receiving a physical book in prison is very meaningful,” Rosario says. “It's not just a book. It represents a prized possession.”

He worries that introduction of ebooks into prisons will lead to the removal of physical books and “that, to me, would just signal that it's in the interest of the Department of Corrections to move towards a more impersonal, less human form of warehousing.”

Book Bans and Restrictions

In the main room of the church basement, each set of Prison Book Program volunteers is dedicated to a task. (“Henry Ford had his assembly line — we’re kinda like that,” Tanner says.) At one table, several volunteers handle the first stage: checking that a letter writer is still incarcerated — an important step, given that the program is always running at a delay. It takes about three to four months to fulfill a request (down from six months, before the program hired its two staff members five years ago, Tanner says). The same person can only send in a request three times a year, to keep levels manageable.

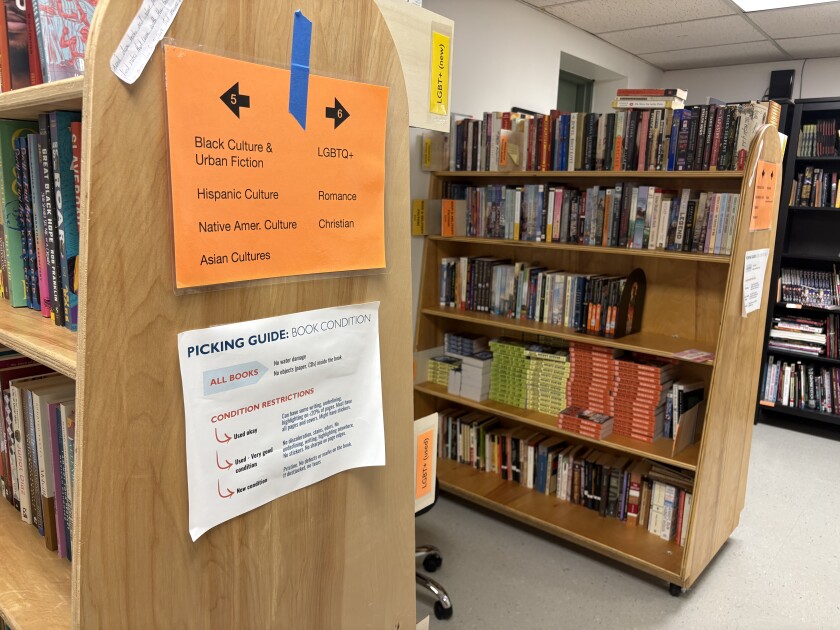

Once an incarcerated person is confirmed, volunteers print out a label listing all the restrictions their individual prison sets on acceptable books. The request then goes to another set of volunteers, who will select best matches from the books at hand.

Prison restrictions range from the obvious — no books on weapon-making — to the idiosyncratic.

“We had a copy of Lord of the Rings returned because it had a map of Middle Earth in it … [and] ‘maps lead to escape,’” Brotzman says.

Some facilities bar materials they want incarcerated people to buy from the commissary, rather than get for free, like coloring books and blank composition books, Brotzman says.

Other times, various fears spark less-common policies, she says. One prison banned drawing books, saying it would lead to tattooing; others ban self-help/empowerment books, saying they could encourage standing up to authority. Sign language books are popular among prisons’ aging population, who Brotzman says often struggle to get hearing aids while incarcerated. One prison barred these books, however, out of concerns that some incarcerated gang members were also using sign language to communicate about contraband.

What Incarcerated People Want

In a side room, Terry, a volunteer, flips through a box of donated books, a letter from an incarcerated person in hand.

“You feel good when you can find something,” she says, like when she was able to meet a request for a specialized, high-level geometry book.

Other times, it can be disheartening: one letter writer’s prison forbade them from receiving a GED study book (“You think you’d want to educate people,” especially so they can get on their feet once released and avoid reoffending, Terry says). And some requests are impossible: this current letter writer asks for erotica and swimsuit photos, things that definitely violate their prison’s rules. Lower down on his list is a request for role-playing games; Terry says she’ll try for that.

Many incarcerated people want hobby books to help them pass the time, books on religion and books that help them learn trades and prepare for work once released.

But one demand beats out all of those: dictionaries.

Jule Pattison-Gordon

While the Prison Book Program largely relies on donated books, no one on the outside has paper dictionaries to donate anymore — so the program buys them by the palette, Brotzman says.

She believes college-level dictionaries are popular both because learning new words unlocks other books and because many people in prison need to understand the legal language in court documents.

Midway through their afternoon, the volunteers break to circle up and share some of the letters they’ve received. One incarcerated person says reading A Walk to Remember helped them connect with their sister; another is from a 65-year-old requesting a GED study book, so they can “prove to my family and myself that I can be an overcomer, not just a statistic.”

For incarcerated people, books can be transformational, says Calvin Arey, who himself was formerly incarcerated and who runs an affiliated book program. He still has a few books he received from the Prison Book Program in the 1970s, back when it was based out of a leftist bookstore in Cambridge, Mass.

In an April email, one of Arey’s regular book recipients, Shebri Dillon, wrote about being filled with sorrow and anger at being kept away from her two youngest children and at still being imprisoned. She wrote about trying to find a sense of peace. Curling up in “this ancient cage of bricks and concrete,” her broken earbud unable to block out the “incessant clanging” on her cellblock floor, she grabbed the first book in her stack, opening it at random. The page turned out to be discussing R. Dwayne Betts, who had been incarcerated for eight years, the same amount of time as Dillon right now, and who went on to become a lawyer.

“To some people, a book is just a book,” Dillon wrote. “But to someone in the throes of the shadows that are closing in on them by the second, fighting to see the light of hope as if it is vital oxygen and they are drowning, this is serious business.”