In Brief:

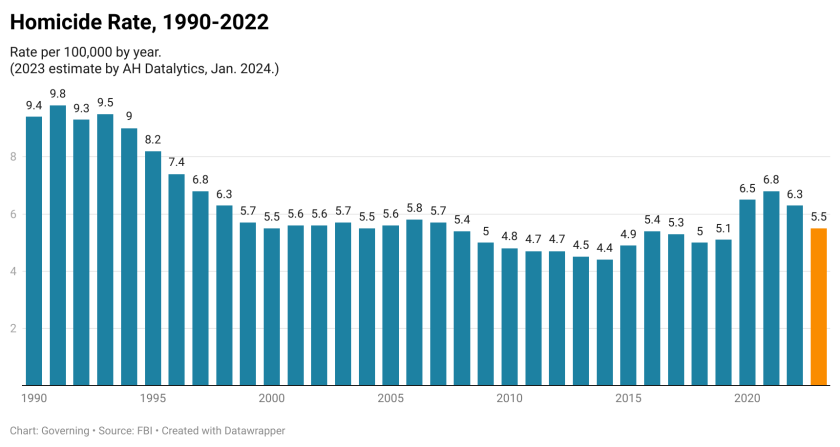

Almost two-thirds of Americans believe crime is a serious problem, a Gallup poll found last month, with 77 percent convinced that crime is increasing. Perhaps few of them would have suspected that the homicide rate had actually dropped 12 percent in 2023, after reaching the highest rates in two decades between 2020 and 2022.

Fewer homicides is cause for celebration, but what about the overall crime rate, including property crimes? It’s difficult to know. For one thing, the federal government itself maintains two different databases. It’s changed one of them, which makes apples-to-apples comparisons over time problematic. Three years ago, the FBI made changes to its reporting system that are still being implemented, and not all local law enforcement agencies are reporting reliably to the feds.

Information about crime trends should be timely, accurate, complete and usable, says John Buntin, project director for the crime trends working group at the Council on Criminal Justice (and a former Governing staff writer).

“Right now, national data is old, hard to use and incomplete,” he says. “Think about watching a football game but then not getting the score until nine months later. That’s where we are with crime data. We’ve got to do better.”

There’s a great need to improve the depth and consistency of data about crime. Data gaps make it possible to assume that if crime isn’t going up, the data must be wrong, says Jeff Asher, a former CIA analyst and founder of AH Datalytics. Better data collection, and a better ability to pinpoint trends whether up or down, could change this.

For law enforcement, the value of data collection has less to do with making comparisons between crime rates over time than with helping agencies focus their efforts by seeing where spikes in crime are occurring, says Rachel Russell, deputy counsel of policy at the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation (TBI).

Based on what is known, however, there’s little reason to accept the suggestion that crime in American cities is at unprecedented levels.

A Three-Decade Trend

The Department of Justice (DOJ) maintains two databases regarding crime in the U.S., one based on crimes reported to police departments and the other on an annual survey of about 240,000 people from about 150,000 households, the National Crime Victimization Survey.

The Uniform Crime Reporting system (UCR), first implemented in 1929, is comprised of reports of crimes and arrests sent to the FBI. The program was redesigned in the 1980s. The National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) was then brought forward in 1988. It allows more complete reporting, but full implementation of NIBRS is still ongoing.

According to data available from the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer, the rates of violent crime, robbery and burglary have decreased steadily and significantly since 1990.

Vehicle thefts are another matter, largely the consequence of social media “tutorials” for stealing Hyundai and Kia vehicles that lack anti-theft protections, and the emergence of such thefts as a sort of sport.

There are hiccups in the data that is the basis of these trends. Until 2020, the FBI continued to accept data submitted through both the UCR and NIBRS. In 2021, it attempted a transition to NIBRS submissions only. As a result, it did not receive data from agencies representing about a quarter of the population, according to an analysis by the Marshall Project. The FBI subsequently said it would accept 2021 data through its Summary Reporting System, but it’s not certain how many agencies responded. In 2022, almost a third of law enforcement agencies did not report data to NIBRS.

In Tennessee, the Bureau of Investigation made a serious commitment to NIBRS implementation and its more detailed accounting of crimes in 1995. In the decades since, it has worked with local agencies to foster accurate collection and submission of crime data through training and certification. Auditors assist in this work and cross check reporting, including follow-up regarding reports relating to incidents that become news.

TBI doesn’t attempt to give “meaning” to the data it collects, says Josh DeVine, TBI’s communications director. “We don’t do independent calculation about things, we simply turn around data as it’s given to us,” he says. “We think that’s the cleanest way to stay in our lane.”

National Data, Local Crime

As noted earlier, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) is based on interviews with citizens, not on crimes reported to the police. The 2022 NCVS survey estimates that only about 4 in 10 violent crimes, and 3 in 10 property crimes, were reported to police in 2022. Estimates for 2021 were roughly the same.

NCVS asks about nonfatal crimes against persons age 12 or older. The count includes crimes reported to the police, as well as those that are not. “Violent crimes” include aggravated and simple assault, rape or sexual assault and robbery. (In the UCR program, this term encompasses aggravated assault, nonnegligent manslaughter, robbery and forcible rape.)

The long-term trend for violent crimes is similar to that seen in UCR data, although there was an increase in 2022. NCVS also shows an increase in property crime — personal larceny, theft, burglary and motor vehicle theft — in 2022. NCVS data does not include crimes against businesses.

John Gramlich, an associate director at the Pew Research Center, believes the NCVS data offers the most accurate picture of long-term national trends because it has been conducted without any change in methodology since 1993, while also including crimes that were not reported to the police.

But he emphasizes that the experience of crime is local. Even if federal data was more accurate, it still wouldn’t tell a lot about what’s happening on the ground, or in real time.

For example, there’s a real increase in violent crime in Washington, D.C., where Gramlich lives, which presents a stark contrast to the generally positive national picture. “Even if you have crime rates for a particular city, that may not be telling the story either,” Gramlich says, “because even within cities, it’s so dependent on the neighborhood you’re in, and even the block you’re in.”

Where’s the Truth?

In a December Substack post, Asher summarized year-to-date UCR data for 2023. Murder “plummeted,” he wrote.

“Americans tend to think that crime is rising, but the evidence we have right now points to sizable declines this year, even if there are always outliers,” he wrote. “The quarterly data in particular suggests 2023 featured one of the lowest rates of violent crime in the United States in more than 50 years.”

“Suggests” is an important concept in regard to all this, taking into account the gaps NCVS has found between the occurrence of crime and what is actually reported to the police, as well as the number of departments that don’t transmit data to NIBRS. Gramlich cautions against thinking that Americans are “out of touch” because they think crime is bad. “I think it’s a little simplistic to just say that people are uninformed,” he says.

There are a number of reasons people could be concerned about crime, despite the better news reflected in national rates. This starts with what’s happening in their own neighborhoods, but also includes media reports and messaging from politicians.

Even if homicides went down 12 percent last year, the total number — about 18,500 nationwide — represents significant loss and tragedy. And homicides are still higher than they were pre-pandemic. “You can be encouraged by the trend while also acknowledging that there’s more work to be done,” says Asher.