In Brief:

Emissions reduction is a first-line defense against atmospheric warming. But as climate pressures have intensified, so has interest in quantifying how much carbon existing and restored natural systems can pull from the air. A public-private collaboration in Oregon has resulted in a unique resource that maps the potential for coastal wetlands to act as “carbon sinks,” absorbing and storing carbon dioxide.

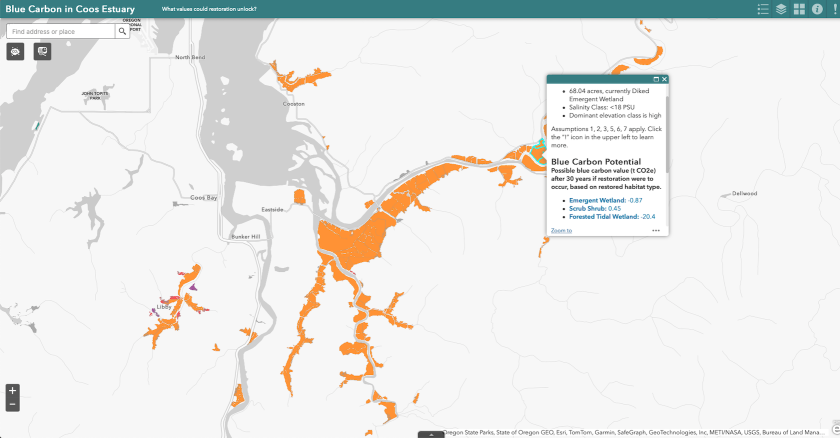

The mapping tool developed by a technical team supported by the Pew Charitable Trusts can guide conservation and restoration in Oregon’s coastal wetlands and estimate the impacts of development proposed in them. It currently covers the Coos estuary, which has a watershed of almost 1,100 square miles. It shows estimated “blue carbon” values for locations within the estuary — the carbon stored in plants, trees and soil in tidal wetlands.

Preserving and increasing carbon sequestration in tidal wetlands is even more urgent due to the rate at which the nation’s tidal ecosystems are disappearing. Estimates of losses from human activity, as well as natural processes such as storms and sea-level rise, range between 60,000 and 80,000 acres each year. These environments are tremendous assets, able to store carbon for millennia, says Meg Reed, a coastal policy specialist in the Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development.

Scientists in Oregon began to look for better ways to map the state’s coastal wetland resources more than a decade ago, says Laura Brophy, director of the Estuary Technical Group at the Institute for Applied Ecology. The convergence of this work with evolving state policy has pushed their efforts well ahead of other states and is informed by the intent to create a model that can be used by others.

Aligning Science and Policy

In 2020, Oregon Democratic Gov. Kate Brown issued an executive order on emission reductions that included a call to outline goals for carbon storage in the state’s “natural and working lands” — grasslands, farms, forests, rangelands and wetlands. A wetlands working group came together in response and published a white paper in 2021 that offered the first estimates of carbon storage benefits possible from restoration projects.

That same year, the Oregon Global Warming Commission submitted a proposal for setting carbon sequestration goals in natural and working lands. It was the first state plan to account for blue carbon in coastal wetlands.

The next step was the enactment of climate resilience legislation in 2023. It established a permanent fund to support conservation and management of natural and working lands to sustain their role in carbon capture. The Oregon Global Warming Commission has been renamed the Oregon Climate Action Commission, with its mission expanded to include these lands.

Last year's legislation also called for state agencies to create an inventory of carbon in natural and working lands; goals for carbon capture in various ecosystems; and strategies to incentivize projects that enhance this capability.

Management of Oregon’s estuaries — areas where freshwater streams or rivers meet the ocean — is guided by a system that is essentially a form of zoning, with units classified according to the level of development allowed in them. The geographic boundaries of these units haven’t been updated since the 1970s, Reed says. The blue carbon mapping tool can play a significant role in reconsidering where restoration and mitigation should be priorities.

More than 90 percent of the forested wetlands once found in Oregon's estuaries have been lost as a consequence of past decisions about land use. Forested tidal wetlands in Oregon store almost as much carbon per acre as Pacific Northwest old-growth forests. “This research and information gathering highlighted how important this ecosystem type is,” Reed says. “I don’t think we really understood that.”

(Laura Brophy)

Satellites and Field Work

The mapping tool utilizes remote sensing data, but it also relies on decades of “boots on the ground” work. Brophy has been working on estuary ecology and restoration in Oregon for three decades, and others involved in the mapping project have spent similarly long periods in the wetlands studying and documenting their characteristics.

Collaboration between researchers hoping to fill blue carbon data gaps gained momentum with the formation of the Pacific Northwest Blue Carbon Working Group in 2015. Enough data has been amassed since then to move into applying it to developing and implementing policy, says Craig Cornu, senior scientist for the Institute for Applied Ecology’s Estuary Technical Group.

“The first thing that any coastal community could be doing to contribute to the overall blue carbon mitigation effort is to conserve what you’ve got,” Cornu says. “It’s the same message that we’ve had for years about tidal wetlands — losing them is the worst thing you can do.”

Carbon storage isn’t the only ecosystem service from Oregon’s coastal wetlands. They provide critical rearing habitat and food sources for young salmon, which live in tidal wetlands for as long as two years before migrating to the sea. Eelgrass beds nurture fish and shellfish valued by recreational and commercial fishermen, including halibut and Dungeness crab. Tidal wetlands help prevent shoreline erosion and protect surrounding areas from flooding.

These benefits can best be augmented if data guides decisions about conservation and restoration. Five or 10 years ago, Oregon was a bit of a black hole in regard to blue carbon data, Brophy says. Today, its inventory is more complete than that of any other coastal state.

“There’s nothing proprietary about what’s going on here,” Cornu says. “We’re developing things with the idea of exporting lessons learned elsewhere, open to anybody asking us questions.”

Finding Balance

Billions of public and private dollars are currently being invested in emissions reduction strategies, from renewable generation to electrifying buildings and transportation. Natural solutions, which can also include reforestation, green spaces in urban areas and farmland management practices that increase the potential for soil to absorb carbon, such as regenerative agriculture, aren’t always top of mind. They also can be expensive.

Any push to expand natural storage capacity also runs up against the pressures of economic development. Although coastal areas are less than 10 percent of the country’s land mass, about 4 in 10 Americans live in them. Population density in coastal counties is more than five times greater than the national average.

The challenge for Oregon’s coastal management program, shared by similar efforts elsewhere, is to find ways to enhance ecosystems and their carbon storage potential while still allowing for economic development. Some researchers have offered analyses of the return on investment from wetland restoration programs, attaching financial valuation to their ecosystem services. A study published in 2022 concluded that the positive economic impacts of restoration projects on flooding protection and carbon sequestration services alone amounted to nearly twice their cost.

It's an open question at this point whether this kind of analysis will be enough to attract sufficient financing to revolutionize wetlands restoration. But Brophy sees it as welcome sign of progress that blue carbon has brought wetlands squarely into conversations about emissions reduction. “They’re definitely some of our most effective ecosystems for sequestering carbon,” she says.