There was talk going around New York that Andrew Cuomo didn’t want to be mayor. It’s not that he didn’t want to win the June 24 Democratic primary. Rather, he saw the job as a stepping stone to his ultimate, undying ambition — being president.

This might always have been unlikely but seems incomprehensible now. Having lost decisively against Zohran Mamdani, Cuomo looks to be finally finished at age 67. He’s been counted out before, but it’s hard to see where or how he could come back, having blown a decisive lead on his home court despite enjoying enormous advantages in fundraising and institutional support.

His loss brings to an end a political dynasty that has been an important force in American politics for 40 years. It’s a Shakespearean tale of ambition becoming hubris. Having avoided the hesitancy that limited his father’s success, Cuomo’s relentless striving turned out to be his undoing.

A Father’s Reluctance

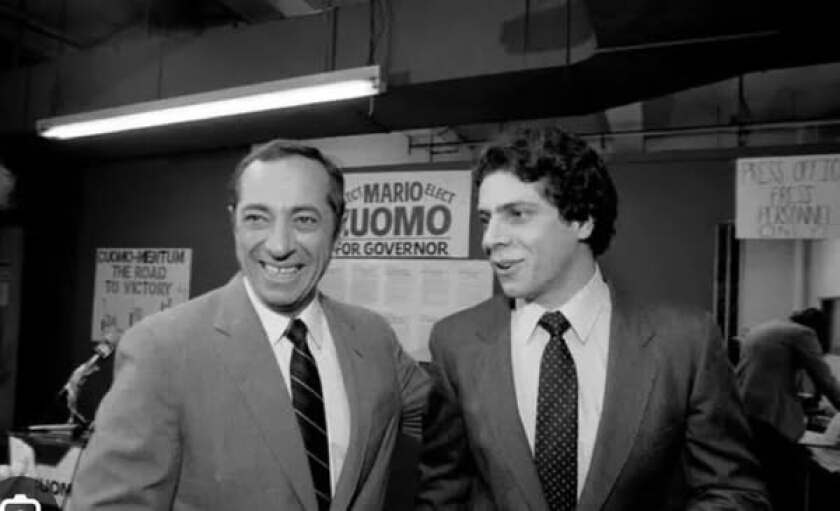

It’s difficult at this point to remember what a big deal his father was, in part because he failed to seize his own opportunities. As governor of New York, Mario Cuomo gave a keynote address to the 1984 Democratic National Convention that turned him into an instant party hero. At the peak of President Ronald Reagan’s power, Cuomo’s sweeping rhetoric convinced Democrats that their New Deal values remained an honorable guiding star instead of what they proved to be with a different presidential candidate that year — a 49-state loser.

Before the 1984 convention was over, delegates were wearing buttons calling for “Mario Cuomo in ’88.” Talk about “drafting” Cuomo to run for the presidency continued for years after. Days before Christmas 1991, a plane waited on the tarmac to whisk Cuomo to New Hampshire for a presidential rally. He ultimately decided to skip the flight, saying that New York’s budget woes made it impossible for him to mount a national campaign.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton considered putting Cuomo on the Supreme Court. Again, Cuomo decided that he would remain in Albany. In the end, he overstayed his welcome. When he ran for a fourth term as governor in 1994. his opposition to the death penalty helped ensure his loss to Republican George Pataki, a little-known first-term state senator, in a year when concerns about crime led to GOP victories across the country.

Andrew’s Long Climb

Andrew Cuomo, who cut his teeth managing his father’s campaigns, would never be described the way Mario had been, as an indecisive Hamlet or even a ditherer. Andrew was always looking for the next chance. He served in the Clinton presidency as secretary of Housing and Urban Development, then mounted an ill-fated bid for governor in 2002.

Cuomo dropped out a week before that year’s primary, having angered many party officials by trying to jump in line ahead of state Comptroller Carl McCall, a prominent African American official. Cuomo also made a remark disparaging Pataki’s response to the 2001 terrorist attacks that seemed to backfire on him. With his characteristic lack of modesty, Cuomo sought to explain his poor showing by saying he had “too many good ideas … When you try to communicate too many ideas, sometimes you wind up communicating nothing,” he said.

He was able to regroup. With state Attorney General Eliot Spitzer in the driver’s seat for the 2006 governor’s race, Cuomo ran to replace him. When Spitzer resigned as governor after being caught sleeping with a prostitute, Cuomo elbowed aside David Paterson, another African American who’d replaced Spitzer. Republicans enjoyed another big year in 2010 but Cuomo was elected as New York’s governor. Four years later, he was sworn in for a second term just hours before his father died.

Andrew the Unloved

Cuomo took some big swings as governor and won a lot of victories. He pushed through a free college tuition plan and made New York a pioneer in recognizing same-sex marriages. He strengthened gun control laws and passed a $15 hourly minimum wage. He built bridges and refashioned airports.

For progressives, Andrew delivered more than Mario ever did. Yet while Mario Cuomo was venerated as a thoughtful philosopher-king, Andrew was castigated as a shark. He seemed shady, killing attempts at addressing corruption in Albany and empowering renegade Democrats who kept Republicans in control of the state Senate.

Andrew Cuomo attracted primary challenges from candidates to his left but he was able to brush them aside. After winning a third term as governor, it looked like he could not only capture the fourth term that had eluded his father’s grasp, but make a plausible run for the presidency.

Women and Money

He’d already raised a fortune for a fourth-term run when the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020. New York City was the initial killing ground in this country but the devastation elevated Cuomo politically. Like other governors, Cuomo raised his profile through daily updates about the disease; his speeches became appointment viewing nationally. And on many nights, he sat for chummy interviews with his brother Chris on CNN.

Andrew was working on a book as a calling card for a presidential run. He wasn’t working alone. Cuomo made use of state resources in producing a book that promised to result in a $5 million payday.

That wasn’t the worst of his sins. Cuomo’s decision to send COVID-19 patients from hospitals back to nursing homes turned out to be a death sentence in many cases. Maybe he used his best judgment based on available medical information at the time but his administration sought to hide thousands of deaths.

And then there were the women. As governor, Cuomo repeatedly touched and made lewd suggestions to multiple women. He tried to suggest that he was just being an old-fashioned flirt but the evidence was damaging enough that Cuomo ended up resigning in 2021.

That Should Have Been the End

At that point, Cuomo was neither mourned nor missed. But having come back from the political dead after his 2002 run for governor, Cuomo believed he could do it again in seeking to become mayor of New York.

Why not? President Donald Trump had been re-elected despite criminal convictions in a New York courtroom. Eric Adams, the sitting mayor, had been indicted (even if charges were later dropped) and was clearly ineffectual. Maybe the moment called out for a tough guy who could get things done.

Cuomo won the support of leading Democrats from Bill Clinton on down. He raised a ton of money. He led in the polls all year against a big field of lesser lights, right up until the end.

Once again, he thought he was untouchable, that power was his to take. He barely made campaign appearances and rarely took questions from the press. Mamdani, meanwhile, offered a hopeful if extremely liberal vision. He turned out to be a social media star. It was Mamdani who had absorbed the rosy part of Mario Cuomo’s dictum that you campaign in poetry and govern in prose.

Andrew Cuomo has never had any poetry in him. Now, he’ll never govern again.