After jumping rapidly amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused supply chains to freeze up at the same time that national governments worldwide were pumping money into their economies with deficit financing, the trend in U.S. monthly price index reports has generally been downward since peaking at 8.6 percent annualized in May 2022. Much of this descent has reflected lower and static prices for “stuff” such as raw materials, commodities and manufactured goods. A good example is lumber, where prices skyrocketed in the pandemic because supplies were cut off while homeowners trapped in their abodes were making property improvements; once the supply-and-demand imbalance began to normalize, prices collapsed. Add to that the economic slump in China where producer prices are actually declining, which will make our imports from them cheaper.

But physical goods are only about one-third of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), with services prices dominating the CPI and the arcane measure of housing costs known as “owners’ equivalent rent” representing a big chunk of that. After rising sharply during the pandemic, housing prices have stabilized and even softened in some locales.

For state and local governments, it’s clear that on average they will see a lower rate of inflation in the prices they pay for lots of the “stuff” they need, whether it’s office and janitorial supplies, or road salt for streets and highways, or police cars. It is a reasonable bet that purchasing officers will have a much easier time in 2024 than they faced in the past 24 months. But labor costs will not be so cooperative. As I explained in a previous column on budgeting during stagflation, the U.S. labor market remains remarkably tight, public agencies must compete as never before with private employers for scarce talent, and public-employee unions are still playing catch-up in their salary demands because the CPI ran way ahead of them in 2021. It’s that catch-up dynamic that bodes ominously as prices otherwise start to settle down.

Disinflation, not Deflation

It’s important that policymakers and public-sector finance managers all know the difference between disinflation and deflation. Deflation is when prices drop across the board; disinflation is when the rate of price increases declines. When inflation goes from 9 percent to 4 percent, that’s disinflation. Deflation is a negative number, which is what those Chinese producers now face.

Although there will likely be specific U.S. markets where prices actually decrease in the coming year or two, that is unlikely to be the broad trend unless the economy unexpectedly plunges into a full-blown recession. More likely is the “soft landing” scenario or what some market economists call “rolling recessions,” wherein various industries take alternating turns in the downswing while others recover, so that overall the general economy, employment and prices remain relatively stable. In that scenario, real growth is anemic, but the nominal growth rate looks positive because of slightly higher prices.

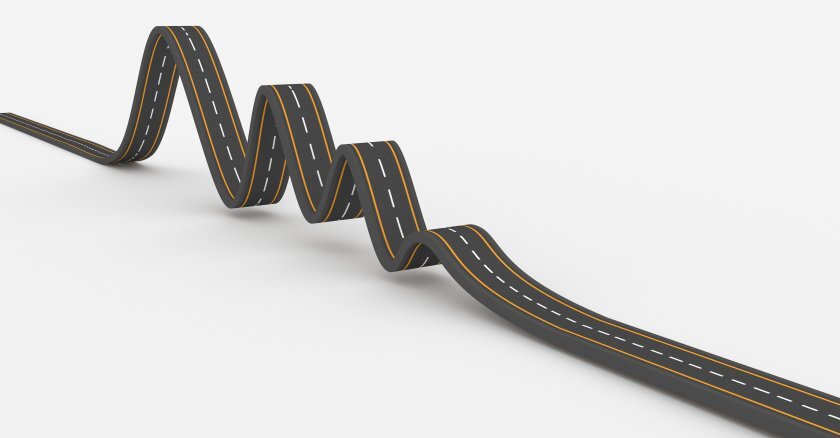

The one prediction I can make confidently is that the coming rate of descent in inflation indexes will not be a straight line. This will be a bumpy ride lower, with a shallower slope. There will be discrepancies and inconsistencies between month-over-month price changes versus year-over-year inflation rates. Headline inflation rates will diverge from “core” inflation, which excludes the particularly volatile food and energy sectors. And any one of the major index components can have an “off“ month with a quirky recording that makes the process look more random than linear if you plot inflation rates on a chart. Economists call those “head fakes” in the inflation data, and we’ll likely see several in the next 12 months.

The economy’s nominal growth rate — which includes inflation — is what probably will keep most state and local governments’ revenue lines above water in the next 12 months, despite shrinkage in various industries and localities. Even income tax revenues, which were headed downward in some states just six months ago because of declining stock prices in 2022, are now looking better because Wall Street has decided that the Federal Reserve is nearly done raising interest rates. Property tax assessments, which nationwide were still playing catch-up from the pre-pandemic surge in home values, are still pretty stable with the exception of office buildings, especially in central cities. So overall, the revenue side of most governmental budgets is still looking to be manageable. It’s the persistent payroll-cost-increase line items that will likely outrun revenues in the next 18 months or so.

Labor’s Turn

Unsurprisingly, we’re seeing organized labor action heating up in various industries outside of state and local government, whether it’s the writers and actors strike in Hollywood or the potential for actions by Teamsters, auto workers, Starbucks employees or airline pilots. Public employees have been relatively quiet on this score so far, but nobody should be surprised to see an increasing number of collective bargaining impasses start to pop up in coming months. And really, who can blame them? The CPI jumped by 12 percent cumulatively in the two years ending in June 2023. I don’t know of a single labor group in the public sector that has enjoyed salary increases that generous, so this is now a process of catch-up. That said, raises cannot exceed available revenues, so there will need to be a middle ground.

One possible creative solution would be for opposing bargaining teams to craft a circuit-breaker on contractual salary increases in the event that employer revenues fall short of the CPI surge. That concept could save face for both sides by acknowledging that nobody can give what they don’t have. But elected officials also need to stop playing Scrooge to score points with taxpayer groups when the revenues are actually there. You can’t credibly cut taxes and then plead poverty to the unions.

It’s not just payroll, of course. There’s also health-care cost inflation for public employees and retirees to take into account. Nurses, doctors and aides are still in short supply, and the cost of most major procedures and drugs keeps escalating, despite politicians’ efforts to negotiate the latter lower. These expenses are a double whammy for public employers who still fund both retirees’ and active employees’ health benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis instead of with prudent advance funding. That hole keeps getting deeper on a national level.

Where there could be some welcome relief over the next 24 months is actuarial pension costs. Although salary increases will also inflate unfunded liabilities for pensioners, those deficits will be amortized over a decade or two. Previously the slumping stock market was expected to crimp actuarial models, but this year’s rally is now likely to bring multiyear average market values closer to actuarial assumptions, depending on their portfolio composition. That math should throttle pension payroll contribution rate increases down a bit, although raw dollar costs will be higher. Once again, expect disinflation, not deflation.

Looking to 2024, the steadily shallower but inconsistent trend toward lower inflation rates will likely allow the Federal Reserve to eventually begin a slow stairstep series of modest interest rate cuts. For treasurers and public cash managers, that could make the coming months ripe for the kind of forward-looking portfolio restructuring that I have suggested previously.

At the very least, it’s worthwhile for public financiers to start thinking ahead as to what happens if short rates drop to around 4 percent by the end of 2024, assuming overall inflation rates slowly slide below that. Don’t expect us to reach the Fed’s goal of 2 percent inflation next year, but hopefully we can see that as potentially possible for 2025 — without the dreaded recession that many feared when this year began. I now say the glass is half full.

Governing's opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing's editors or management. Nothing herein should be construed as investment advice.