A new report from Brookings, released this week, found that more than half of the 387 metropolitan areas studied show little readiness to make AI an economic driver. Rural areas and small cities were especially likely to be unprepared.

But AI doesn’t have to just serve the same cities that have always been known for their tech dominance. Strategic interventions can help many more areas participate.

“This is potentially a truly transformative technology that can greatly increase the productivity of people, firms and places,” says report co-author Mark Muro. “So, it really does matter who has access to it. … If we really do care about some degree of connection and equity among regions, I think this is something that we need to understand.”

In addition to boosting workers’ and businesses’ adoption of the technology, regions should prepare for undesirable side effects, like workers losing their jobs and the hefty water demands from data centers.

What Communities Can Do

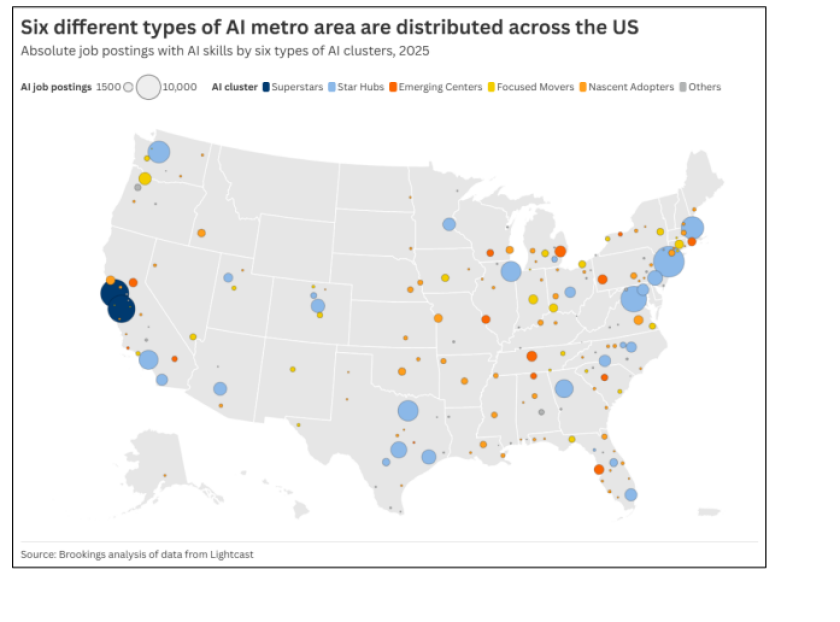

Strong performing cities have several of the three “pillars” of an AI-ready economy, per the Brookings analysis: plenty of local talent with AI-related skills, such as degrees in computer science; local businesses that are interested in, and able to take advantage of, AI; and local AI research and development. Austin, Boston, Seattle and other metro areas along the northeast and west coasts and Sun Belt hit all three areas. A wider range of areas have at least two pillars but still need to build up an additional key area. Tampa; Pittsburgh; and Madison, Wis. are among this list.

The report argues that the right strategies can help metropolitan areas move further, whether they’re far on their journey or just starting out.

“There’s been so much discourse with so many kinds of competing viewpoints, I think it's been hard for regional leaders to make sense of it, understand where they are, and then take actions,” Muro says.

To help guide leaders, the Brookings report charts how metropolitan areas stand up against their peers, while also outlining key areas of strength that jurisdictions should focus on building to be ready to make AI an economic driver.

Brookings Institution report "Mapping the AI economy: Which regions are ready for the next technological leap?"

Massachusetts is one community that conducted a self-assessment. The governor created a task force in 2024 to study how AI could benefit the state economy and create recommendations on how AI can be used by sectors like education, health care, financial services, life sciences and robotics.

Communities that find they have very little AI activity can get started by just raising awareness of the technology, through efforts like AI 101 workshops in schools, community colleges and business associations, per the report. Meanwhile, communities that need more local talent could look to help public higher ed and high schools teach AI-relevant courses.

Mississippi is one state that’s been making a big push on AI education. The Mississippi Artificial Intelligence Network (MAIN) helps coordinate between state government, public higher ed, tech companies and some other business sectors. It aims, in part, to prepare people to use AI for different careers. Initiatives have included creating “AI labs” at higher education institutions with technology to support AI-related education and research, various free self-paced AI trainings for all residents and a free intro to AI course to nearly 3,000 K-12 educators.

Communities that want more business adoption, meanwhile, can try various strategies. They might work to educate local companies about the possible uses of AI, and local governments might consider demonstrating AI use cases by piloting the technology for low-risk routine tasks like basic chatbots, per the Brookings report. Communities also want to pay attention to how AI could serve the employers already in the area. In North Dakota, for example, an organization called Grand Farm tests how new technologies can support agriculture.

Preparing for the Downsides

Of course, being ready for AI also means being ready to mitigate its undesirable effects. For one, some professionals will likely lose jobs to automation. The Bureau of Labor Statistics anticipates AI will cause employment to decline in several professions from 2023-2033. Threatened jobs include medical transcriptionists; customer service representatives; credit analysts; insurance claims adjusters, examiners and investigators; and auto damage insurance appraisers.

The Brookings report authors suggest the federal government and local governments could provide temporary financial support for displaced workers who've lost their jobs, as well as subsidies for them to undergo training to get on a new career track.

“This is something that has not been talked about enough,” Muro says. “National discourse and the industry discourse is very much about accelerating build-out, with much less discussion about the fortunes of the workers who are affected by that.”

Another downside? Data centers tend to need vast amounts of electricity to power their computers and huge amounts of water for cooling. In 2023, data center-heavy Virginia saw the centers use a quarter of all electricity sold in the state. Not all communities interested in AI may want to supply these resources. Oregon and California have proposed legislation intended to stop data center activities from driving up residents’ utility bills.

Areas that do not want to encourage local data centers can still take advantage of AI by connecting to further-flung computing resources. Some areas are looking to put more limits on them: Santa Clara reportedly began requiring any new data centers to use renewable energy, and it banned a particularly water-intensive kind of cooling. Responding to data centers’ added water and energy demands is a larger issue that the nation will need to determine how to answer.