“We're already hearing from state and local health departments that there are both hiring freezes and job cuts on the table as states begin to remodel their budgets,” says Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association. “We also know that we start with a baseline of insufficiency.”

The CDC is providing nearly $900 million from CARES Act funds to state and local jurisdictions to help with surveillance, testing, contact tracing and other functions, but these funds don’t address pre-existing needs.

“We’re about $4.5 billion short,” says Benjamin, referencing a white paper from the Public Health Leadership Forum. “That is just the bare minimum that would allow us to respond to public emergencies like these.”

It’s possible that the shock of the shutdown, and the central role of testing and monitoring in recovery plans, will provoke willingness to fund public health at this level.

The First Pandemic of the Information Age

A recent poll from the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that about half of all Americans have a high degree of trust in coronavirus information from state and local government. In response to this degree of public confidence, public health websites have greatly expanded the Web-based tools they use to fill the information gap about COVID-19.New Jersey has been a hot spot for the virus, with more deaths per capita than any state except New York. “The state’s COVID-19 hub includes continually updated information on questions people might have on all aspects of COVID-19 issues and the state’s response, and also corrects rumors and misinformation,” says Nancy Kearney, communications manager for the New Jersey Department of Health.

A contact tracing registration hub has yielded 48,000 responses from persons interested in joining this effort. Retired health professionals can sign up to help in the response, and citizens can donate PPE for those on the front lines.

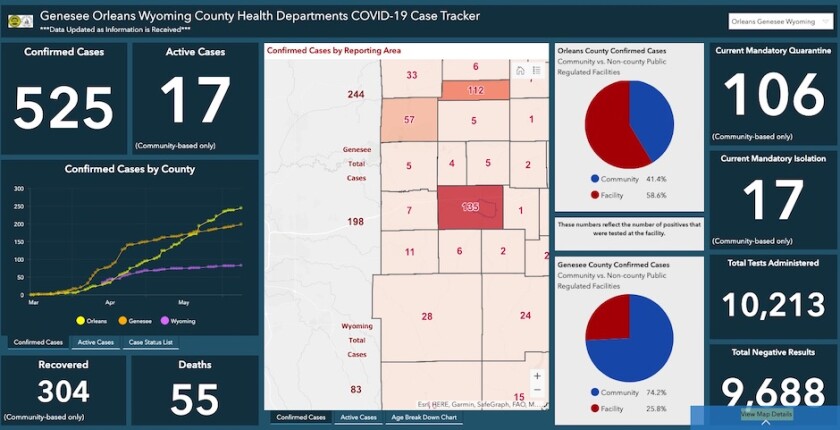

In addition to aggregating data on cases, locations and hospitalization, the site includes a symptom checker, and a dashboard that maps cases and trends, demographics and other data. The dashboard was built using software from Esri, which develops mapping and spatial analytics software.

Esri is making this technology available at no cost to public and private organizations to help update reporting with map-based dashboards, forecast capacity needs with spatial analytic tools and select locations for new and augmented services like testing sites and food distribution locations, according to Esri’s chief medical officer and health solutions director, Dr. Este Geraghty.

Crowd Control

One of the most sobering research findings about the outbreak came from a study funded by the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation. The researchers concluded that implementing social distancing guidelines on March 8 rather than March 15 would have prevented 36,000 COVID-19 deaths.To help health officials monitor changes in crowd behavior, Google has developed a Community Mobility Reports tool that uses anonymized, aggregated data to track changes in the number of visits to places such as retail stores, grocery stores, parks and transit stations.

Community mobility reports can help public health officials see where crowds are gathering. (Courtesy of Google.)

“Knowing the general pattern of how a community moves can play a critical role in responding to the novel coronavirus and preventing future pandemics,” says Dr. Sara Cody, health officer and director of the Santa Clara County Public Health Department. “This information can help us understand how seriously people are taking the shelter at home order and what additional steps might be needed to slow the spread.”

Digital Contact Tracing Gains Support

Another step in controlling the pandemic is to follow the movements of people who are infected with COVID-19. “It is critically important for public health officials to be able to scale up and mobilize a well-trained contact tracing workforce with enough personnel to fulfill this important protective measure without overburdening or burning out the individuals doing the work,” noted Lori Tremmel Freeman, chief executive officer of the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO), in announcing a new tool that can help public health officials estimate the number of contact tracers they will need.Google and Apple have collaborated on a tool that could add to contact tracing efforts, even if states manage to recruit and train the nearly 200,000 that NACCHO believes are needed. They have developed an application programming interface (API) that local agencies can use to build their own contact tracing apps.

The apps won’t replace the hands-on efforts of tracers who interview COVID patients and track down those with whom they have been in close contact, but they could give public health officials additional insight into when, or even where, transmission might occur.

“Contract tracing is a complex endeavor that does require human resources,” said Dr. Karen DeSalvo, chief health officer for Google and former health commissioner for New Orleans, in a May TED interview. “On the other hand, there’s an opportunity to better inform the contact investigators.”

The API, which is interoperable between Apple and Android devices, helps public health agencies to create apps that use Bluetooth to create an anonymized log showing when other devices are near enough, for sufficient time, to constitute “close contact.” This data can be used to help an infected person better remember where he might have been and who was nearby.

In some cases, apps could allow users to receive notification if they have been near a confirmed case. It remains to be seen whether privacy concerns or hiccups with app development keep citizens from installing these apps, but phone-based technology has played a role in successful containment efforts in other countries.

Tech Helps, But Not a Substitute

The full range of IT resources for public health also includes chatbots, AI, remote monitoring and data visualization. But given the ground that needs to be covered to make up for years of underfunding, local public health departments may not be ready for all of them.“The optimal tools for local health departments are ones that integrate text, mobile, and Web interfaces for patient engagement and improvement of reporting,” says Dr. Oscar Alleyne, NACCHO’s chief of programs and services.

“We should remember that these technologies don't replace people,” says the APHA’s Benjamin. “For those health departments that are still doing contact tracing and sharing information by pen and paper, by Excel spreadsheets being faxed or emailed from one place to another, good technological tools that allow them to do their work are important.”

Investment in both people and technology are vital, not just for pandemic response, but to address critical public health issues that are being neglected as scant resources are reallocated to contain the coronavirus.

“I'm just looking at what we spent having to shut down our economy,” says Benjamin. “If we had been able to be more efficient and faster, at least 36,000 lives and billions of dollars would have been saved.”