In Brief:

- Reorganization at FEMA has worsened long-standing workforce challenges at the agency.

- A new report details capacity issues that could become problems if a major storm strikes the U.S. during the current hurricane season.

- State and local emergency managers agree that FEMA could use improvement, but they want a voice in reimagining it.

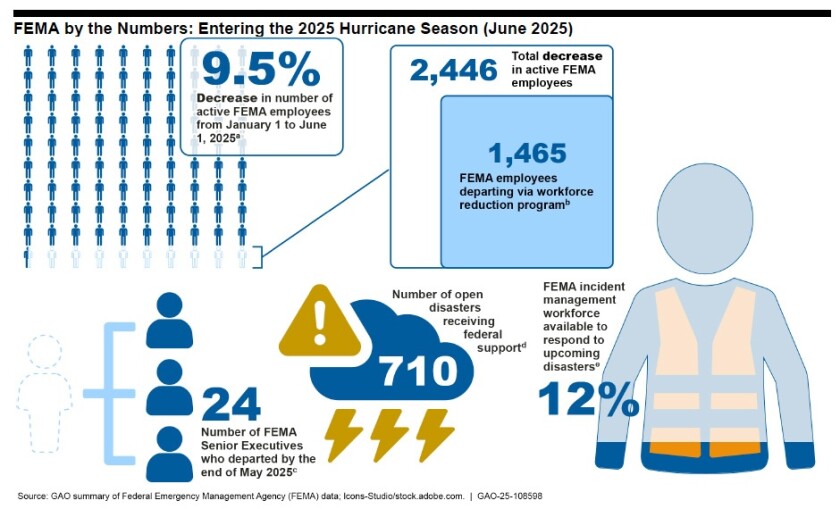

When hurricane season started in June, only 12 percent of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA)’s incident management workforce was available to respond to any disaster that might come, according to a new report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

The remaking of the agency has reduced FEMA’s workforce by almost 2,500 employees, including senior executives. FEMA officials told GAO that workforce reduction programs have created “significant skills gaps” within its leadership.

Last January, President Trump established a review council to advise what needs to be done to improve FEMA’s “efficacy, priorities and competency.” In a March executive order, he called on states to take a more “active and significant” role in disaster resilience and preparedness.

Review and recommendations — and implementing changes — will take months, if not longer. A hurricane season predicted to include three to five major hurricanes is happening now. GAO’s findings suggest that a high-impact storm might overwhelm FEMA’s current capacity.

Lynn Budd, president of the National Emergency Managers Association (NEMA), says this doesn’t mean her colleagues will be helpless if a disaster strikes. “We’re used to responding to things that are unexpected,” she says.

Budd, director of homeland security for Wyoming, says emergency managers recognized FEMA could use improvement long before the current administration. States would like to see changes such as shorter waits for disaster declarations, less administrative complexity, more flexibility in using disaster funds, and better coordination between FEMA with other agencies. Emergency managers are supportive of the push to fine-tune the agency but want to be included in conversations about reform.

More Events, Fewer Workers

GAO evaluated FEMA staffing during hurricanes Helene and Milton and the January wildfires in Los Angeles. The goal was to identify lessons learned from these events and the impact of recent changes on future federal response.

Its investigation was wide-ranging, from review of applicable laws, recent orders from the White House and personnel records to interviews with FEMA officials and site visits to areas affected by the hurricanes and wildfires.

The report found that FEMA staff were stretched past capacity in responding to the disasters. The scale of damage from Helene and Milton was immense. After Helene, major disaster declarations were made for Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. FEMA obligations for these two events are estimated to be four times greater than for the Los Angeles fires.

The close succession of these disasters further strained FEMA capabilities. Overlapping events is an ongoing challenge — GAO reports that at the start of the 2025 hurricane season, there were 710 open major disaster and emergency declarations still receiving federal support of some kind.

This isn’t a new problem. FEMA has had long-term staffing shortages and workforce management issues, GAO reports. When the 2024 hurricane season began, just 17 percent of its incident management workforce was available. Staff were already in the field supporting 80 major disaster declarations.

FEMA isn’t the only agency involved in disaster response, Budd says, but it is the coordinating agency. The most frustrating thing at present is the many unknowns, and lack of communication about how it will operate in face of the inevitable next event.

“We can prepare for just about anything you can think of, but we have to know what it is,” she says.

(GAO)

The Right Kind of Support

Budd would like to see a deeper dive into what states really need from FEMA. Having the right support (and the right amount of it) is most important.

Emergency managers assist each other outside of FEMA through the Emergency Management Assistance Compact, an all-hazards mutual aid system created by Congress. There’s no backup for this system, and at present funding for it is in jeopardy. Congress must engage in conversations about how to continue this funding, Budd says.

In April, FEMA announced it was ending support for disaster mitigation. NEMA has been in conversations with the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, and Budd says funding for mitigation is in its FEMA reform bill.

The report from Trump’s review council will be part of the ongoing conversation about reform, Budd says. Congressional response to council recommendations will be another part, and so is input from state directors.

“We can't stop hurricanes, we can't stop tornadoes, we can't stop any of those things,” she says. “But we can better prepare our communities to recover, and we can do a better job of supporting them through that recovery.”