However, while many local leaders want to move toward more equitable methods of governing, fines and fees make up a significant amount of revenue for many small and mid-sized cities and counties. Even local governments without excessive revenue generation from fines and fees still need to utilize these charges as a part of their budgets and as a deterrence for those who would violate codes and laws. So what can local leaders do to address these seemingly dueling interests?

In a word: “segment” — that is, move from flat, one-size-fits-all pricing toward fee structures that charge residents based on what they can afford. Segmented Pricing for Fines and Fees, a report published by the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) as part of the Rethinking Revenue initiative, makes the case for right-pricing fines and fees by proving a seemingly paradoxical idea: When cities lowered fines, revenue actually increased.

A few months ago I had the opportunity to record a podcast with the report’s co-authors, Jean-Pierre Dubé from the University of Chicago, Bryan Glenn of the technology company SERVUS and Shayne Kavanagh from GFOA. “Right-pricing” is something that I’ve long supported at the local-government level. It involves not only reducing fees when that seems needed but also not underpricing assets for those who can pay, because loss of revenues also reduces the opportunity to address inequity.

When I was mayor of Indianapolis, we applied this construct to city-owned golf courses. Some of those in higher-income neighborhoods were underpriced, especially on weekends, while others were overpriced. Seniors on limited incomes, for example, could benefit from lower green fees, especially during the week when the courses had more availability. I segmented the pricing by audience and time not because I wanted to penalize the affluent golfers but because I didn’t want to underprice our assets. Underpriced assets force a compensating payment somewhere — higher tax subsidies or higher green fees across the system. And I still gave golfers the choice to play at their old rate during certain days and times.

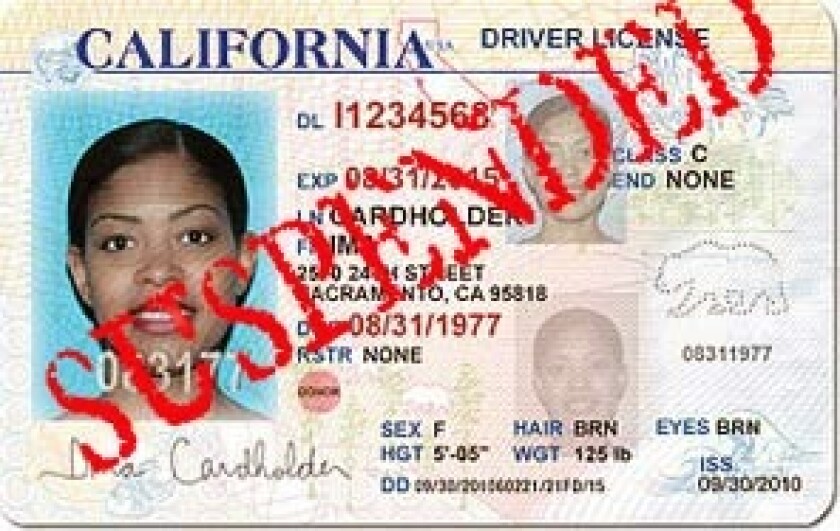

Dubé, Glenn and Kavanagh believe that this kind of segmentation is broadly applicable; rather than golf course pricing, they lay out a case for implementing segmented pricing for things like utility bills, parking citations and court fines. These are three examples of “large collection streams,” where local governments typically have considerable uncollected debt on their balance sheets but also where low-income residents are more likely to experience cascading negative repercussions like water shutoffs, revoked licenses or even jail time.

Once the revenue stream to segment is chosen, the city should gather data on who has been or may be unable to pay, based on factors such as average area income or participation in government assistance programs, and begin to assign each segment of this population a different discount. One group may receive a fine at a 10 percent discount, while another may receive 20 percent. City data teams can assist with gathering the data and randomly assigning discounts, then reviewing how often a given discount led to a payment to determine the right-pricing sweet spot. This benefit is not at the expense of the city; segmented pricing is not a “free pass,” and it doesn’t require the city to cover any lost revenue.

Dubé explained that there is much more elasticity to fines and fees than traditionally expected: Just as a shopper of limited means might buy a computer only if a cheaper, lower-end model is available, if a resident gets a bill for a parking violation in an amount that they can actually pay, they're more likely to. As this demand-curve graph from the GFOA report shows, the number of payments goes up when price goes down. (“F1” is the standard fine amount; “F2” represents a hypothetical lower price, while “FN” is the lowest price offered.) Many more people paying a slightly lower rate produce more revenue for the city; higher rates equate to more non-payments and reduced revenue.

“Segmented pricing offers an opportunity for local governments to take the lead on bolstering their cash flow and improving the lives of residents,” says Glenn. He, Dubé and Kavanagh are currently recruiting cities for a segmented fines and fees pilot project. I encourage any interested cities to reach out about participating in this innovative opportunity.

Governing's opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing's editors or management.

Related Content