The busy thoroughfares of 47th Street and Indiana Avenue were crowded with men arguing in front of tenements, women shepherding their children down the sidewalk, knots of gamblers in front of bars and groceries, people of all ages greeting each other as close friends. There were small businesses with sometimes puzzling signage (“Optometrist — radios repaired also”).

There was much in those close-knit communities that I couldn’t see but learned about later: social clubs, numbers games, charity outlets, locally owned funeral parlors and insurance offices, young people looking in on the disabled and the elderly.

That world disappeared a long time ago, as we all know. The vibrant streets of Chicago’s Black South Side gave way to monotonous clusters of high-rise public housing in which maintenance was neglected and residents feared for their safety. This wasn’t just happening in Chicago; it became a fact of life in cities all over the country.

I know a fair amount about this, but it is still hard not to be struck by some of the facts about public housing in America in the third decade of the 21st century. In New York City, for example, 20 percent of violent crimes occur within 100 feet of public housing. Just 3 percent of households in public housing comprise two adults with children; a majority of the units are occupied either by single mothers or by the elderly poor. African Americans make up about 14 percent of the U.S. population; they are 42 percent of the population of public housing.

All these numbers and many more appear in The Projects, a new book on the decline and fall of public housing by one of its longtime students, Howard A. Husock of the American Enterprise Institute. Husock’s book is both a defense of the community life of the postwar years in Black neighborhoods, slums though they may have been, and a critical dissection of the elitist social ideology that put an end to that life and replaced it with the dysfunctional high-rises that became ubiquitous in urban America.

The Projects isn’t primarily an exposé of the current condition of public housing — though it gets into that — but rather an inquiry into the intellectual forces that brought it about. He starts with a long-forgotten but historically crucial event, the Modern Housing Exhibition held in 1934 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Its promoters numbered not only change-minded housing specialists but leading philanthropic and activist citizens, including first lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

The key word was “modern.” The exhibit’s designers shared a belief that the squalid conditions of the urban slum were to a large extent a consequence of failing architecture and deteriorated properties. Replace the existing dilapidated buildings with modern new ones, they proclaimed, and the stain on urban life would disappear.

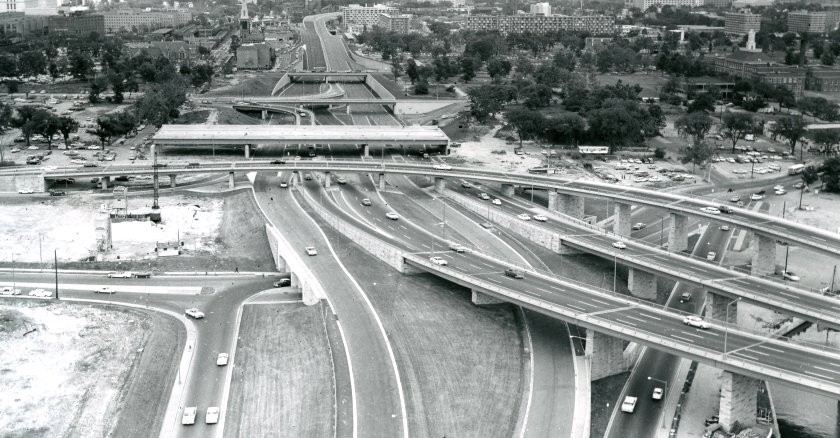

In this conviction they were echoing the theories of Le Corbusier, the Swiss-born urban planner, who believed that existing urban conglomerations were disastrously dirty, crowded and conducive to misery, and that downtowns didn’t need to exist at all. They could be replaced with clean but antiseptic “towers in the park,” eliminating unplanned cheek-by-jowl city neighborhoods and creating superblocks devoid of corrosive physical proximity, connected only by automobile and devoid of any street life.

WHY ANY INTELLIGENT PERSON should have believed this is difficult to fathom today, but in the 1930s it was an article of faith among policy intellectuals convinced that they knew what the urban poor needed, even though they rarely set foot in the existing city slums and understood virtually nothing about what life in these precincts actually was like. They never bothered to ask slum dwellers what sort of neighborhoods they needed or wanted. They had no conception of the pungent vitality that existed in the mean streets of neighborhoods like the ones I visited as a kid in Chicago.

Le Corbusier wrote of “meditation in a new kind of dwelling, a vessel of silence and lofty solitude” and declared that “there ought not to be such a thing as streets.” Today this can only strike us as laughable. But foolish as it was, it became the basis of most of the public housing built in the United States between the 1930s and 1970s. Most of those sterile, isolating high-rise towers are gone now, but we are still living with their unfortunate consequences.

It was in 1961 that Jane Jacobs exposed these fallacies in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, explaining that active street life didn’t corrode poor communities; it preserved them and made them safer. More than simply calling for the demolition of low-income neighborhoods, the reformers of the 1930s were reflecting a belief that poverty was a function of physical surroundings, not a social phenomenon. It took Jacobs to drop that mistaken idea into the dumpster where it belonged. But by then the damage had been done.

The modernist movement and the museum exhibit that expressed it were the catalyst for decades of American urban policy. They were the intellectual underpinning of the Housing Act of 1937, which allowed communities to clear out low-income neighborhoods under the auspices of eminent domain, and the even more consequential 1949 Housing Act, which codified the authority of local governments to demolish virtually any blocks they labeled as blighted.

Those laws made possible the urban monstrosities of Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago and Brewster-Douglass in Detroit, among many others. In nearly all these cases, it was promised that the residents displaced by new construction would eventually be allowed back into their communities at reasonable rents, but very little of this actually happened.

By the late 1960s, these once-promising icons of modernist public housing had already begun deteriorating. They were made even less livable by a 1969 congressional amendment that limited the rent a public housing authority could charge tenants, depriving project managers of the funding they need to maintain their buildings in livable condition. The perception of high-rise public housing as afflicted by broken elevators, malfunctioning utilities and lethally dangerous corridors wasn’t just a stereotype; in many of the projects, it was a reality.

Studies documenting these conditions led the Nixon administration in the early 1970s to declare that the era of building high-rise public housing, partially subsidized by the federal government, was over. To the extent that Washington would address the housing needs of the poor, it would be by providing vouchers to help them rent private apartments in any section of a city and in any properties that would accept them.

These so-called Section 8 vouchers made very little dent in the problem of poverty; in many places, they created newly dangerous slums out of marginal neighborhoods that were relatively stable until the Section 8 tenants arrived. Soon it was difficult for Section 8 recipients to obtain decent housing anywhere in the cities where they had been living.

THE PAST COUPLE OF DECADES have seen a new generation of experiments designed to do something about dilapidated housing and urban poverty. One was to level the worst high-rises and replace them with low-rise mixed-use projects in which the poor could live alongside middle-class residents and presumably absorb parts of their lifestyles and values.

Evidence of the impact of mixed-use developments remains inconclusive; they have clearly helped some tenants rise out of poverty, but incomes for most of the low-income tenants have not risen substantially and crime rates remain uncomfortably high. Even as a partial success, they are difficult to scale up to the level that would replace the overpopulated towers that were demolished to create them.

Husock doesn’t offer any panaceas to solve the problems of housing the poor. He displays some enthusiasm for the Obama administration’s Rental Assistance Demonstration program, which provides private developers with federal contract funds against which they can borrow money to keep up their properties. So far this has registered some successes, but it clearly hasn't solved all problems in this area.

The clearest idea that comes through all this history is that the slums of the 1940s and 1950s didn’t need to be leveled. The apartments could have been renovated at a cost far smaller than the amount it took to build Robert Taylor or Pruitt-Igoe. But there’s limited value in simply being nostalgic about what might have been.

Still, it does suggest what may be the most important insight that Husock leaves us with, one that extends far beyond the failures of public housing. Poverty isn’t the result of bad architecture, dingy apartments or crowded conditions. It isn’t the result of any design strategy at all. It is the residue of an entire complex of social factors, many of which are ameliorated by the communal institutions that exist in the poorest places.

“Poor neighborhoods can be good neighborhoods,” Husock concludes, “and their replacements will not be inevitably better, especially for those who are uprooted.” It is a lesson that the housing activists of the 1930s never bothered to learn. We can only hope that we have learned it now.

Governing’s opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing’s editors or management.

Related Articles