Politicians and government officials are beginning to agree, with some taking up the call to “defund” police departments. New York Mayor Bill de Blasio recently announced plans to divert money from the nation’s largest police force to social services.

Responding to this crisis of faith, the National Conference of Mayors has assembled a working group of mayors and police chiefs to make reform recommendations. The group's principles call for resetting “the compact between police and communities they are sworn to protect."

“That’s not zeroing out policing, but looking how to take some of what we're investing in policing and spend it things that are as effective, or more effective, that don't have the downsides for communities that some kinds of policing investments can have,” he says.

Excessive force may be the “downside” that has pushed attitudes about America's "law and order" system to the brink. But reform must also explore the ways that equating punishment with accountability has damaged and degraded millions of American lives.

Low Bar, High Stakes

An estimated 13 million misdemeanor arrests are made each year in the U.S., accounting for nearly 80 percent of criminal dockets. So many Americans have criminal records that, if they held hands, they could circle the earth three times.Petty theft, simple assault, possession of marijuana, public order crimes and DUI are the most common misdemeanor offenses. Others include such things as not wearing a seat belt, trespassing, graffiti writing, riding a bicycle on a sidewalk or panhandling.

Racial disparity in arrest rates for misdemeanor offenses is large and consistent, and has been for decades. This is all the more controversial because in many instances it is left to the officer to decide whether an arrest is even made.

The sheer volume of misdemeanor cases means that public defenders and judges focus on moving cases through the system rather than the pursuit of justice. Guilty or not, those who are poor find their fragile finances destroyed by the cost of bail, fines and fees, or end on probation, at risk of more criminal charges because they can’t pay.

University of California, Irvine professor Alexandra Natapoff, the author of Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal, worked as a public defender in Baltimore. “The misdemeanor process commonly strips the people who go through it of their liberty, money, health, jobs, housing, credit, immigration status and government benefits,” she writes.

It can be even worse. The fatal police shootings of Michael Brown and Philando Castile and the chokehold death of Eric Garner all occurred when an officer decided to stop a citizen for a minor and non-violent misdemeanor offense.

Strategies to avoid such destruction do exist. For decades, law enforcement and community members in some jurisdictions have created programs to divert offenders from a system from which they may never recover and enable them to repair the damage they have done.

Another Kind of Justice

Stephanie Clark is the director of the Center for Justice Reform at the Vermont Law School. She describes an exercise she does with students.“I’ll ask them what they think of when they think of criminal justice,” she says. “I get all kinds of answers – jail, courtroom, judge, attorney.”

When she asks them what “justice” means to them, she observes, “You’ll get all these other words that we don’t ever associate with the criminal justice system – things like equity, fairness, inclusion, transformation, support.”

Clark and her colleagues are working to bring criminal justice into alignment with these concepts. Vermont Law School established the nation’s first law school-based Master of Arts program in restorative justice, and in partnership with the University of San Diego, the University of Vermont and the U.S. Office of Justice Programs it hosts the National Center on Restorative Justice to advance education, training and research in restorative justice principles.

Restorative justice offers an alternative to punishment and isolation. Its techniques center around inviting people who have experienced harm and those who have caused that harm to come together and to work out a way to make things right again.

“Most people who have been victims of crime want to heal as much as they can and to have some kind of assurance that what they experienced is not going to happen to someone else,” she says. “The system we have right now is not designed for this, but people are starting to realize that restorative justice offers a way to change the landscape.”

Better Than Mediocre

The Vermont Department of Corrections oversees a network of community justice centers at 20 locations throughout the state, some run by nonprofit organizations, some based in local police departments, funded by the department.This work began in the late 1980s, under the direction of the commissioner at the time, John Gorczyk. Behind the move were vocal citizens dissatisfied with the performance of the department, says Derek Miodownik, who serves as the department’s restorative and community justice executive. Thresholds for incarceration were low, parole board releases were few, jails were crowded and citizens were distrustful and displeased.

“The public was complaining that people were not coming back safer or better after incarceration and that there wasn’t accountability for how the community was harmed,” says Miodonwik.

Gorczyk likened the corrections department to a private sector company with the community as its customers, and decided to do what a private company would do. Even though the department was insulated from market forces, he believed “that doesn’t give us the right to be mediocre,” says Miodownik.

The commissioner hired a market research firm to survey Vermonters about what they wanted from the criminal justice system and followed this with focus groups.

“Communities wanted people who were incarcerated to get treatment and education so that they came back better off,” says Miodownik. "If offenders didn’t need to be incarcerated, Vermonters asked for the opportunity to make real the harm and the social contract violation caused by their misdemeanor behavior.”

Based on the feedback, the department announced planning grants that would enable communities to develop community justice centers based on restorative principles. Their services have evolved continuously over the past 25 years.

Early on, probationers were ordered to attend weekly meetings at their local justice center for a year. Panels comprised of trained facilitators and volunteers from the community would engage the offender in discussions about the impact of their crime and work collaboratively to find ways to make up for any damage and ensure further offenses did not occur. This process has been shown to lower recidivism rates, Miodownik says.

Over time prosecutors and state’s attorneys began to divert misdemeanor cases to the centers, to give those who did not want to contest charges a chance to avoid court and a criminal record. It also frees court resources to address serious crimes. By the mid 2000s, high-risk offenders were also being referred to the centers.

“You need to take people who are most socially isolated or most marginalized and insert other people into their worlds so that, over time, a degree of reciprocal care is created,” says Miodownik.

A Process of Unlearning

Restorative Response Baltimore has also been in operation for more than two decades. One of the first programs of its kind in a big city, it is a model for others in restorative justice community, nationally and internationally. Even so, not everyone in a city with a deep need for its services knows it’s there.“I’ll facilitate something, and parents or kids or teachers will say, ‘I can’t believe this is a thing, where have you been?’” says Kasai Richardson, one of the center’s facilitators and its communications manager. “We’re in a renaissance, I guess, where everything that is going on nationwide is making people realize this is an option for them.”

Restorative Response Baltimore has been operating for two decades and is considered the first program of its kind in a big city.

Although it only takes cases in Baltimore, Restorative Response is the hub for a network of partners in Maryland, as well as facilities in New Orleans, New York and Oakland.

Sometimes community members, particularly young people, tell staff at the center that what Restorative Response offers is “a white thing,” and that they deal with their problems in the streets.

“We gently remind them that it was an unlearning over many decades or centuries that brought us to thinking that we’re not able to talk,” he says. “We say that wisdom is in the community.”

The center takes referrals from the Baltimore Police Department and the state attorney’s office, from schools and communities and the department of juvenile services. In cases where charges have been filed, they are dropped if the parties involved can resolve their conflict and the person who committed an offense keeps to their agreement.

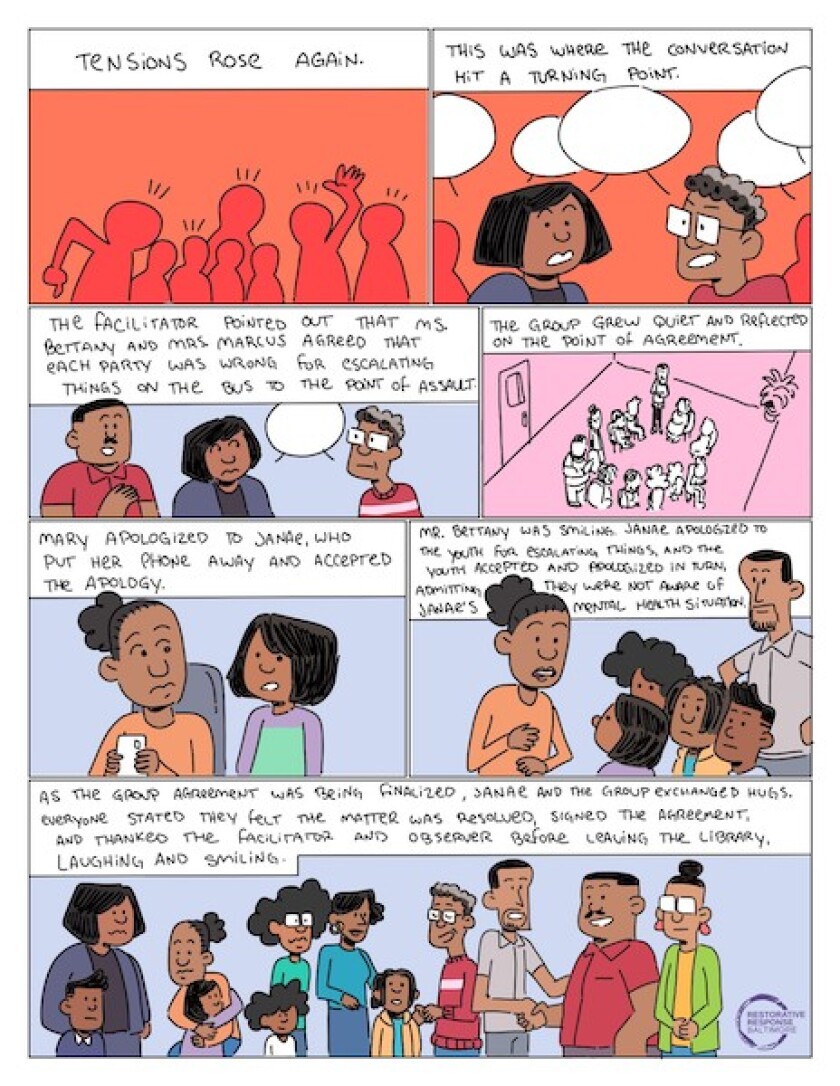

Participants in restorative processes gather in circles, a simple and ancient signal that they are meeting as a community. Everyone has a chance to speak, and the group works together to find a resolution that satisfies all concerned. This could mean an apology, making amends through repaying the costs of damage, an act of service — whatever seems truly fair to all parties.

“If these processes are not in place, this conversation’s not going to be had,” says Richardson. “Relationships continue to erode and things escalate, and all too often that escalation is going to be violent and even deadly.”

Space for New Approaches

Mainstream discussions of police reform have already moved well beyond de-escalation training, but eliminating punishment altogether has not emerged as a priority. Though this may be a long-term aspiration, restorative programs belong high on the list of strategies that deserve public funding.The Urban Institute’s Jannetta recalls the 2015 push to reform police departments from within, in response to the crisis caused by events including the shootings of Michael Brown and Freddie Gray. Body cameras, training and other interventions were put forward as solutions, but five years later, little has changed.

“The longer you’re doing reforms to solve problems within institutions without it appearing that the problems have been solved, the more that’s going to open space for bolder approaches,” says Jannetta. “A number of the things advanced as fixes don’t appear to be fixing the problem.”

Miodownik sees an opportunity to invigorate democracy itself, devolving responsibilities to citizens such as those who volunteer to participate in community circles. “We talk about transparency, but permeability is better yet, having the community at the table and impacting process,” he says.

As is the case in other issues facing government, the pandemic has added urgency. “The inequity of Black and brown people dying at higher rates than their white peers has dovetailed into the economic issues, has dovetailed into criminal justice,” says Richardson.

Safety predicated on the threat of violence is not real safety, he maintains.

“How safe does one feel now with all these police, with all these prisons?” he says. “It feels disingenuous to say that trying another way would be so much worse when things are going the way they are now.”