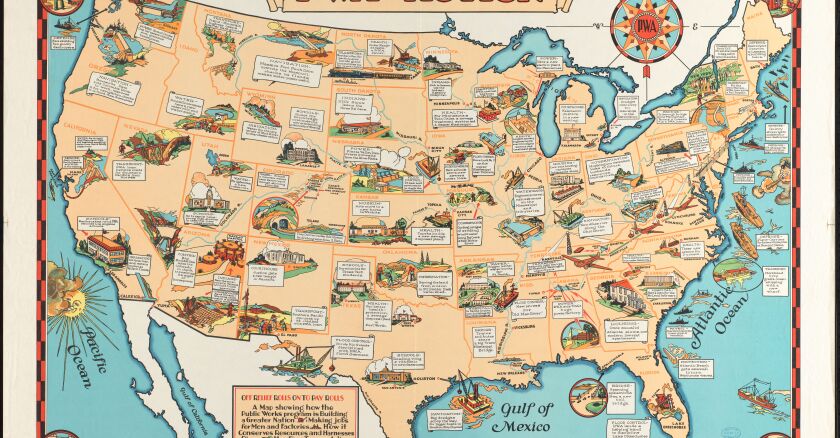

But the comparison with Joe Biden is perhaps more apt, in both his willingness to break with economic precedent and his desire to spend big on infrastructure. As the vicissitudes of a polarized and undemocratic Senate pull at his legislative program, it remains unclear if he will be able to match the efforts of the 1930s, where Public Works Administration (PWA) funds were spent in 3,068 of the 3,071 counties in America.

But Biden at least appears to have learned from both Roosevelt’s and Obama’s efforts to use public works to fight unemployment. As University of New Mexico professor Jason Scott Smith explores in his book Building New Deal Liberalism, infrastructure spending may be a poor cure for mass unemployment but it is essential for long-term economic development. (That’s why Biden decoupled the two, with separate stimulus and infrastructure bills.)

Governing talked with Smith about Biden’s American Jobs Plan, the role of state and local officials in national infrastructure efforts, and whether all these analogies to the New Deal are overdrawn.

Governing: There’s a narrative that’s dominated our understanding of the New Deal which argues that it failed to quell the Great Depression and only World War II brought an end to mass unemployment. Your work centers the history of the New Deal on government-funded construction and argues that it actually succeeded on those terms. How does looking at the New Deal through that lens alter our understanding of the period?

Smith: A lot of the historical interpretations depend on what you are judging the New Deal against. If you’re judging it against the goal of eliminating mass unemployment, well, it fell short of that. But it did cut mass unemployment in half during Roosevelt’s first term of office, from what he inherited from Hoover.

If you shift your metrics for assessing the impact of the New Deal to include not just the jobs created, but the infrastructure that was built, then you see a more wide-ranging impact. The New Deal’s investment in infrastructure makes America’s postwar productivity possible, makes a postwar national marketplace possible, and positions the United States to be the first among the two superpowers at the close of World War II.

There’s a whole host of ways that this set of investments in infrastructure had massive Cold War implications. But it also just had everyday community applications from the schools, to the swimming pools, to the roads, to the sewers, to the courthouses that are built in all but three counties across the nation.

Governing: There is an argument that World War II was essentially the largest public works program in American history, and that’s why it definitively ended the Great Depression. But even before World War II, you document that a lot of New Deal public works dollars were spent on the military. Between 1933 and 1935, 45 percent of PWA funds were spent on military installations. Why is it apparently so much easier to muster the political will to spend big on national security, as opposed to civilian infrastructure?

Smith: I’m going to shy away from giving you a global answer, but I can give you a context-specific answer in terms of the early ’30s. It’s because the New Deal was facing critiques for all the delays and logistical difficulties in reviewing and approving plans, funding them, executing the projects, getting things started, getting things built. It’s an unwieldy, long, tedious process to get public works spending and construction started. The New Deal is essentially setting up entire federal bureaucracies over the first 100 days and beyond, facing such granular questions as do we have enough typewriter ribbon and typewriters to process forms? Where are the filing cabinets?

In the quotidian nature of setting up new bureaucracy to execute public works projects, it is a huge help to have an already existing department, like the War Department, that has infrastructural needs and clear line items that can be funded. In the context of the Great Depression and needing to address the crisis of mass unemployment, it was pretty straightforward to say, we can build aircraft carriers, we can improve and expand military bases. On the one hand, military officials were eager and vocal about wanting funds and on the other you had a New Deal public works program, a growing bureaucracy that wanted to show that they were trying to address the crisis.

Governing: What role did state and local governments play in the success of the New Deal, which is often seen as the moment when the federal government rose to its current prominence and became the expansive state we saw during the second half of the 20th century.

Smith: This is an origin point for the increasing centralization and increasing powers of the federal government. But what’s missed if you stop there is all of the ways the New Deal works in a partnership with states and localities. You really see this with the public works programs. The federal government was not dictating to states and cities what they should build; rather, the states and localities proposed projects and sent their plans into Washington, D.C.

Their proposals and plans were reviewed by the New Deal’s engineers, construction experts, people from the Army Corps of Engineers that were working for the Public Works Administration. They reviewed these plans, they evaluated them for their soundness, their ability to generate employment, their worth in the society that was proposing them, and then they made funding decisions. States and localities often pledged, in the case of the Public Works Administration, their own matching funds in order to secure federal loans and grants.

States and cities were voting in a sense with their own dollars for these public works projects that were created by the New Deal. This is not the federal government reaching its tentacles into the states, communities and localities and telling them what to do. Rather, this is the federal government responding to states and localities and building what they are proposing.

Governing: What effect did all this spending have politically? You cite a study that found that the amount of relief money spent was not directly reflected in Roosevelt’s popularity, and that instead the performance of the overall economy was more directly related to his poll numbers. How should Biden administration policymakers consider the political dynamics of public works spending as they face midterm elections in 2022 with a closely divided Congress? I’m sure they’re hoping that they can pull off a win like 1934, where Roosevelt bucked the trend that the president’s party loses midterm elections.

Smith: I think the only president to do it after that was George W. Bush and the midterms after 9/11, for very different reasons. It’s difficult to measure voter intention, and the reasons that people decide to vote for candidate X or candidate Y, because of policy A, B, or C. From what we can see from the historical record about the intentions and thoughts of Roosevelt and his advisers, there was a belief that good policy would ultimately make for good politics.

The Biden administration is already thinking about the midterms and about how to represent their undertakings, their policies to the American people. They’re taking their cue from the Obama administration, and how the Obama administration could have been much more active and vocal in telling their story about the stimulus act that was passed in response to the financial crisis of 2008. This was a huge missed opportunity. Michael Grunwald’s bookThe New New Deal is very persuasive that that was a federal policy that had a lot of beneficial impacts, but that no one told that story in a way that got traction. Biden doesn’t want to make that mistake.

Governing: Obama stood in stark contrast to FDR in his messaging, or his lack of it.

Smith: Look at the speeches Roosevelt gave in the 1936 election campaign, when he’s running for re-election the first time. It’s noteworthy that FDR goes, in many cases, to visit public works projects that have been built by his administration during his first term. He talks about the very American nature of this federal spending. He’s not presenting it as a dramatic departure, but rather describes it as in spirit with what the nation has always done to respond to crises, to invest in its people. He carries on an electoral campaign that points to the concrete achievements of his first term and the American people chose to go with the new dealer who was delivering, rather than the person who was critiquing the New Deal.

Governing: How useful are these New Deal analogies? They were made a lot during the Obama years and now, again, during the Biden years. But we are a very different country today. In the 1930s, the American state was not very well developed. There was a lot of room to grow, basic capacity building that had to happen. So how useful are these kinds of analogies for analyzing policy and politics today?

Smith: History never tells us what to do, but it can offer us a great storehouse of perspective. We can’t expect that we can look back at the granular policy measures, the alphabet agencies created during the 1930s, and make a one-to-one Venn diagram overlap of what to do in our present moment. And I don’t think anyone is saying that. But the widespread interest in making this comparison indicates a hunger for national leadership to create effective and dramatic change.

I think it also indicates something that we often forget about the New Deal. The New Deal was hugely popular, but it was also tremendously controversial at the time. In 1939, Gallup did a public opinion poll and asked Americans, what’s the best thing Roosevelt has done and what’s the worst thing that Roosevelt has done? The No. 1 answer to each question was the same thing, the Works Progress Administration. It was tremendously popular for putting people back to work and building infrastructure. And it was tremendously controversial for exactly those reasons.

They were employing people at a time when unemployment was seen as a personal fault. Many people thought, why should the government help you, if you can’t even help yourself? The government intervening in society to provide infrastructure and jobs, that was a controversial thing to do back then. It’s still controversial today.