Voter turnout for local elections, typically held in off-cycle years, has historically lagged behind state and federal races set to take place in November, but recent results suggest it’s slowly becoming even worse.

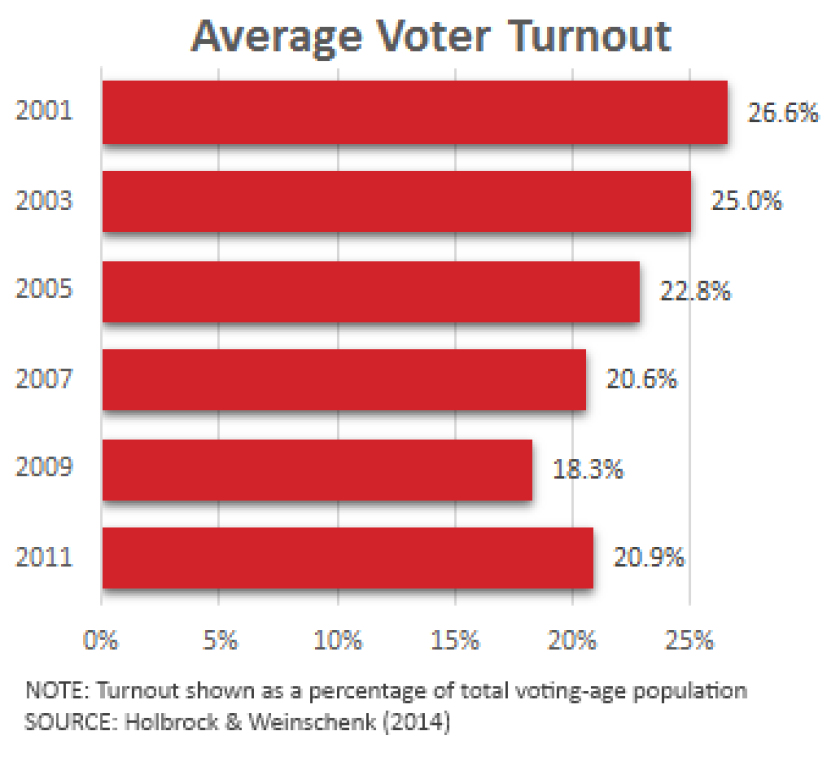

University of Wisconsin researchers provided Governing with elections data covering 144 larger U.S. cities, depicting a decline in voter turnout in odd-numbered years over the previous decade. In 2001, an average of 26.6 percent of cities’ voting-age population cast ballots, while less than 21 percent did so in 2011. Turnout for primary and general local elections fluctuate from year to year, but long-term trends in many larger cities suggest voter interest has waned.

If local turnout doesn’t improve, the implications could extend much further than the ballot box. Low-turnout elections typically aren’t representative of the electorate as a whole, dominated by whiter, more-affluent and older voters. Recent research published by a UC San Diego professor found such elections contribute to poorer outcomes for minorities, including uneven prioritization of public spending.

Long ago, political machines routinely mobilized a healthy cadre of big city voters with often predictable results. Later, during the 1960s and 70s, more than two-thirds of registered voters cast ballots in New York, Los Angeles and elsewhere when power shifted to racial and ethnic minorities. But now, voter participation in big cities is typically low, prompting officials to explore ways to get more people out to the polls.

In Los Angeles, officials formed an elections reform commission after the city’s dismal turnout in 2013. Commission Chairman Fernando Guerra, who directs a research center at Loyola Marymount University, attributes the city’s declining turnout rates to a lack of partisan competition from Republican candidates and a diminishing racial divide. “No longer is a Latino running for mayor a major challenge to the status quo,” he said. Municipal candidates may hold different views on a few issues, but when they’re of similar backgrounds and political leanings, the differences appear less stark to voters.

Of all proposals to boost voter turnout, moving the election date to coincide with state or federal elections has, by far, the greatest effect. That’s what the commission in Los Angeles has proposed to do. Weinschenk’s research indicates that shifting mayoral elections to presidential years results in an 18.5 percentage point jump in turnout, while changing to November of a midterm election yields an 8.7-point average increase.

Even-year elections can also save taxpayers money. The Maryland General Assembly voted to delay Baltimore’s next local election by one year, lining it up with the 2016 presidential election to save the city an estimated $3.7 million.

So why haven’t more localities moved their municipal elections? The top concern often cited is that local races receive less voter and media attention when they appear on crowded ballots. Holding elections in off-years also allows elections offices to try out new procedures and better train staff.

Guerra doesn’t think those are good enough reasons not to make the shift. “It’s not right to define voters as informed or uninformed,” he said. “Whatever system leads to the greatest number of voters participating is the one we should implement.” The lower the turnout, the less Guerra said voters resemble the entire electorate. In cities like Los Angeles and Houston, it’s often the Hispanic precincts that vote at the lowest rates.

Other recommendations of the Los Angeles commission include improving voter registration outreach, creating a network of early voting locations, promoting voting by mail and using shopping centers and other non-traditional locations as polling places. A separate panel also recently proposed that the City Council study offering cash prizes to randomly-selected voters, the legality of which is a bit murky.

Some argue merely getting more people to the polls won't inevitably yield the best government. “We naturally assume more turnout is better, but that’s not necessarily always the case,” said Eric Oliver, a University of Chicago professor who has written a book on local elections. This thinking suggests voters can't just head to the ballot box without being informed as well.

While generally low, big cities’ turnout rates vary greatly. Many on the low end are in Texas -- only about 11 percent of registered voters cast ballots in the most recent mayoral elections in Fort Worth and Dallas, both of which held competitive open-seat contests. By comparison, 44 percent of registered voters came out for San Diego’s special mayoral election earlier this year.

Research suggests partisan local elections experience higher turnout rates, in part because nonpartisan contests lack cues that motivate voters to turn out. Localities in which mayors have more power also see higher turnout rates. Differences in voter turnout in local and higher-level races aren’t nearly as apparent in many other countries. In fact, voters typically participate at greater rates in municipal elections than national races in Japan and France.

According to Oliver, barring a scandal or major initiative, local politics mostly functions in an “equilibrium state” that isn’t conducive to generating voter interest. Interestingly, although Americans aren’t apt to vote in municipal elections, Gallup surveys indicate they trust local government more than the state or federal levels.

Motivating more voters to participate in local elections is difficult. But while governments can’t instill voters with enthusiasm, Oliver said they can make it easier for citizens to find information and remove barriers preventing people from voting to make for a stronger, more representative government.

Voter Turnout Declines in Largest U.S. Cities

SOURCE: Chicago Board of Election Commissioners, Los Angeles City Clerk, New York Board of Elections, Office of the Philadelphia City Commissioners

NOTE: Turnout shown for general mayoral elections and special elections in Chicago, New York and Philadelphia. Los Angeles holds nonpartisan mayoral primary elections; results also include runoff elections.