As a former Paralympian, it brings me great pride and joy to see these people not only compete at the highest level but also celebrate their abilities, which help to motivate those who live with a disability while inspiring millions of others. However, it would be remiss of us to ignore the challenges that people with disabilities have here in the U.S., particularly when it comes to the equipment needs of those who wish to accomplish the terrific feats Paralympic athletes do.

Racing wheelchairs and other mobility technologies specific to sports are expensive, and the costs aren’t typically covered by health insurance. Standard racing chairs can cost over $2,500. While standard bicycles for casual cyclists rarely exceed $1,000, handcycles, which are great for people with impaired legs, are commonly sold for over $2,000. But many people with disabilities must pool their finances toward the health care they need on a daily basis, and the high costs of such adaptive sports technology limit the number of aspiring athletes.

The technology used to propel these athletes, as well as everyone in the disability community, has come a long way since the first Paralympic Games were held in 1960, at a time when it was commonly questioned whether these people could compete in adaptive sports at all. In those days, athletes typically used clunky, heavy hospital-issued wheelchairs.

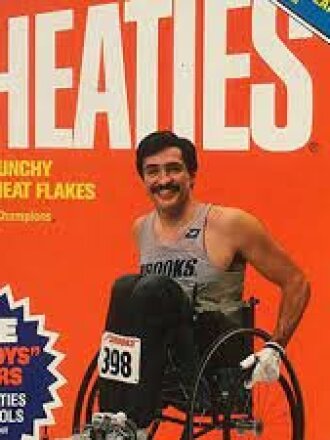

It was only until the 1980s that chairs began to incorporate lightweight materials customized for individual athletes, which made for better overall performance in competitions. You may remember George Murray from your Wheaties box back then: In 1988, he became the first wheelchair racer to break the four-minute mile.

It’s up not only to companies but also to policymakers to increase access to sports for people with disabilities, and not just at the world-class level. Our local communities should provide easy access and inclusivity for athletes with disabilities. If we can get equipment to schools, local clubs, municipal facilities and universities where people can try it, we can create more Paralympians and promote increased health. Sports courts and complexes can also have equipment tailored for these athletes. City governments’ parks and recreation departments can help create and expand these opportunities.

Sports and recreation should be accessible for all. If you enjoy watching the Olympics or Paralympics, we need to create more opportunities for people to get there.

Many great strides have been taken in the effort to increase visibility and inclusivity for the disability community since the signing of the Americans With Disabilities Act of 1990. But it’s clear, looking at the struggles disabled people have with not just access to adaptive sports equipment but also to everyday transportation, shopping, or employment, that there are still many strides to go.

Rory Cooper is director of the Human Engineering Research Laboratories at the University of Pittsburgh. He won the bronze medal in the 4x400-meter wheelchair racing relay in the 1988 Paralympic Games in Seoul. He can be reached at rcooper@pitt.edu.

Governing's opinion columns reflect the views of their authors and not necessarily those of Governing's editors or management.