Well, that was then. Nearly all the resistance to COVID-19 vaccines is coming from Republicans. A Gallup poll released last week found that a small majority of Republicans – 56 percent – have received at least one dose of a coronavirus vaccine. That’s well below the 92 percent found among Democrats, and it’s a lower percentage among any subgroup defined by race, gender or region.

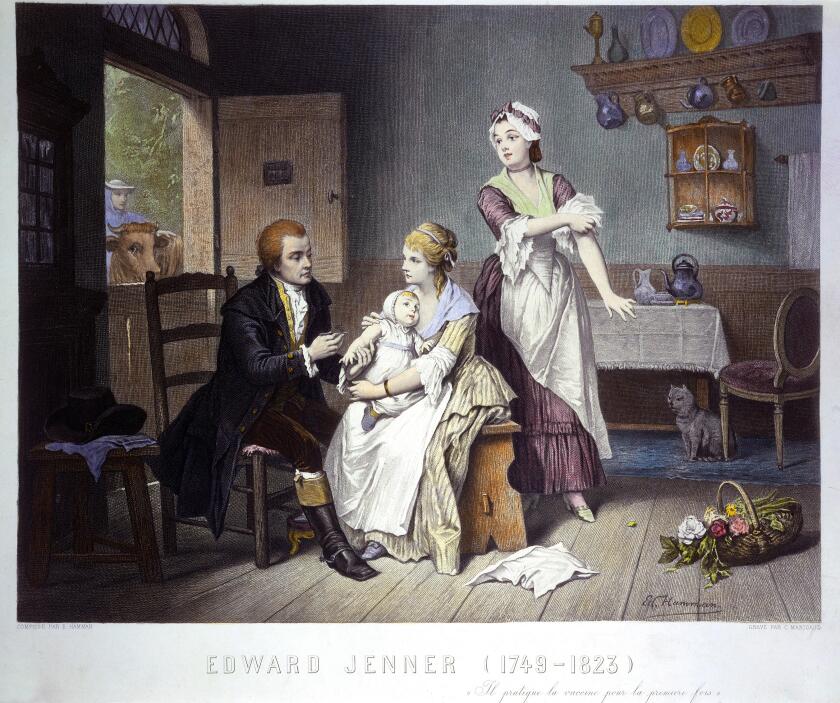

There has always been resistance to vaccines, starting with the earliest smallpox vaccines of the 18th century. In recent years, vaccine hesitancy occurred on both the left and right, with low rates of measles vaccination in liberal enclaves such as Boulder, Colo., and Marin County, Calif. One of the most prominent vaccine skeptics is Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a scion of the liberal dynasty. “Prior to the pandemic, anti-vaccine activists fell roughly evenly along political party lines,” says Jonathan Berman, author of the book Anti-vaxxers.

But as anti-vaccine activism has grown during the pandemic, Berman notes, it’s become more partisan in nature. Opposing mandates and insisting on individual freedom to choose are messages that have resonated strongly among conservatives, particularly libertarians and white evangelicals.

“Major advocates of vaccines are experts and government officials – two groups that the GOP base despises,” says Jack Pitney, a government professor at Claremont McKenna College. “So if these insiders are for vaccines, a lot of Republicans figure that they have to be against them.”

Governors and other elected Republican leaders generally encourage vaccines, but louder voices among conservatives, including Fox News, conservative talk radio hosts and activists, have cast doubts about vaccine safety. Being hesitant about vaccines at this point has become, along with masks, a symbol of partisan identity.

Last month, dozens of individuals staged a protest at a Staten Island mall, angered by New York City’s proof-of-vaccination requirement for indoor dining, chanting “Fuck Joe Biden.”

“There are no other diseases where people’s response to treatment is driven by their ideology, but COVID-19 has fallen into that trap,” says Joshua Sharfstein, vice dean of the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University.

Divisions and Distrust

Partisan divisions run deep. It’s not just that Republicans and Democrats disagree over issues such as taxes and health care. Many now view people on the other side more like enemies than misguided compatriots. A poll released last week by the University of Virginia Center for Politics found that 80 percent of Biden voters and 84 percent of Trump voters see elected officials from the opposing party as “a clear and present danger to American democracy.”

Distrust is especially strong among Republicans. Recent polling from Pew has found most Republicans distrust media, government and institutions such as K-12 education, higher ed, unions, technology companies and other corporations. The only major institution most Republicans trust at this point is churches. “There’s a demographic sort of low-trust people into the Republican Party in a way you hadn’t seen before,” says Sam Rosenfeld, author of The Polarizers: Postwar Architects of Our Partisan Era. “It’s a kind of disposition that can now be activated.”

People who are hesitant about vaccines don’t trust the systems we have in place, says Jennifer Reich, author of Calling the Shots: Why Parents Reject Vaccines. They’re wary, for instance, of the relationships between drug makers and federal regulators. They tout a pro-freedom message, rejecting the idea that the state should be able to compel you to do something you don’t want to do, including having your children vaccinated.

“What happened right away, when we had stay-at-home orders, is that it created an opportunity for those same claims to resonate in an apocalyptic way,” says Reich, a University of Colorado Denver sociologist. “It underscored that anti-government, personal freedom ethos: ‘See – we told you that you’d have no freedom.’”

The Importance of Messengers

From the very start of the pandemic, people’s willingness to change their behavior – for instance, by washing their hands more or staying home – has been determined more by partisanship than any other factor, including age, race or geography, according to Shana Kushner Gadarian, a Syracuse University political scientist who has been studying public responses to the pandemic.

“The partisanship subsumed everything else,” she says. “Across every dimension, not just of behavior but attitudes, partisanship stood out.”

If there was an opportunity for a Pearl Harbor or 9/11-style call to national unity, President Trump didn’t take it. Trump, who had amplified anti-vaccine messages prior to his election, openly feuded with Democratic governors over their stay-home policies and cast doubt on medical experts, including those serving his own administration.

His administration greatly sped the vaccine development and manufacturing process, spending billions on Operation Warp Speed, but Trump held an ambiguous relationship to vaccines – sometimes touting them, sometimes seeming to prefer the kind of untested treatments that are now widely touted in conservative media as alternatives to vaccination. Trump frequently downplayed the severity of COVID-19, saying it was nothing to be afraid of even after he caught it.

Numerous Republicans have underscored the importance of vaccination, including Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, a polio survivor. “It’s time to start blaming the unvaccinated folks, not the regular folks,” Alabama GOP Gov. Kay Ivey said in July. “It’s the unvaccinated folks that are letting us down.”

But such messages aren’t breaking through with everybody. Trump himself was booed at an Alabama rally when he recommended vaccination. Meanwhile, conservative activists – groups such as Turning Points USA and Eagle Forum and even individuals facing criminal charges for their roles in the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol – are helping lead the vaccine resistance.

“It is really the case that Republican elites are picking up the loud minority behavior and views of their base and shaping their own messages around that,” says Rosenfeld, a political scientist at Colgate University.

Consequences Over the Long Haul

When the COVID-19 pandemic first struck the U.S., its victims were mostly residents of blue states, notably New York and New Jersey, along with cities that tend to vote Democratic such as Chicago, Detroit and New Orleans.

At this point, with the vast majority of COVID-19 deaths occurring among the unvaccinated, it’s Republican areas that are having the worst problems. As of the middle of last month, 53 percent of people in counties that voted for President Biden were fully vaccinated, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, compared to 40 percent of Trump county residents. The death rate in counties that Trump carried by 70 percent or more has been nearly five times as high as counties where he carried less than a third of the vote, according to health analyst Charles Gaba.

The preponderance of COVID-19 deaths since the spring has occurred in the solidly Republican South, with Texas and Florida alone responsible for 30 percent of the deaths since June 15. People are twice as likely to die in rural areas, now Republican strongholds, than cities.

Although there was vaccine hesitancy prior to the pandemic, vaccines were broadly supported and mostly depoliticized. Now we have a situation where anti-vaccine sentiment has become a bedrock principle of a minority – but a substantial minority – of Republicans. “For a lot of Republicans, it has become a matter of identity,” says Claremont McKenna’s Pitney. “For them, opposing vaccines is like donning a MAGA hat or sporting a Trump campaign button.”

There’s now a tribal feeling about vaccines that’s hard for people to shake. Rather than sorting through the scientific truth, people are making a quick calculation that it’s more important to remain part of their partisan group. And there are sincere beliefs – encouraged by some conservatives – in the mistaken notions that vaccines are dangerous while COVID-19 itself is no big deal.

“This anti-vaccine sentiment has always been around, but a major difference is now you have a major party in a two-party system at least giving a little bit of a nod to people who are vaccine-hesitant, or in some cases more than a nod,” says Charles Allan McCoy, a sociologist who studies public health at the State University of New York Plattsburgh.

Once an issue becomes politicized, it’s difficult to put aside the partisan feelings triggered by it. Already, Republican state officials have limited the power of local health authorities in the midst of the pandemic. There’s now a concern that opposition to COVID-19 vaccines could spread to other vaccines.

“We’re battling this in the states right now,” says L.J. Tan, chief strategy officer for the Immunization Action Coalition. “They’re moving a lot of bills, playing exactly on the message of autonomy and personal freedom: ‘If you believe this is true for COVID vaccines, you should think it’s true for all vaccines.’”

Related Articles