In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, conservationists worked to create national, state, and local parks to protect parcels of nature. An often overlooked element of this movement is the active role that women played in leading conservation efforts throughout the United States.

One of the earliest and most successful of these conservation movements spearheaded by women was the creation of Franconia Notch State Park in New Hampshire. Nestled in the White Mountains, Franconia Notch became a popular tourist site in the 19th century. Middle-class tourists would stay at one of the local hotels and participate in hiking, camping, and other scenic activities.

Authors and artists further popularized the region by depicting the landscape in paintings and literature. Nathaniel Hawthorne, for example, published a popular short story about the Old Man of the Mountain (also known as the Great Stone Face), an anthropomorphic cliff in the Notch that quickly became a New Hampshire icon.

(Digital Commonwealth)

The state government agreed to provide a portion of the funds needed to purchase the Notch. However, they asked SPNHF to raise the remaining $100,000 required for purchase. To achieve this fundraising goal, SPNHF turned to a prominent group of local women activists.

The New Hampshire Federation of Women’s Clubs (NHFWC) was a social reform group focused largely on conservation issues. Their self-identified mission was to preserve “God’s gift of exceeding beauty to our hills and valleys,” and they even adopted the Old Man of the Mountain as their club symbol.

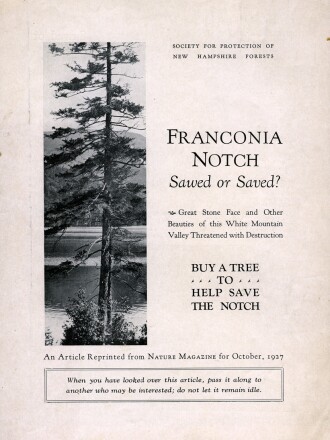

NHFWC quickly endorsed the cause of conserving Franconia Notch and collaborated with SPNHF to raise $100,000 through a multi-pronged fundraising effort. First, the organizations began a “Buy a Tree” campaign in which donors could give a dollar to symbolically own a tree in Franconia Notch. The organizations promoted the campaign as a way to memorialize a family member lost in World War I. They advertised the campaign in local, state, and national publications, including outdoor publications such as Field and Stream and Nature magazine, as well as New England newspapers like the Boston Globe.

(White Mountain Art & Artists)

Second, the organizations collaborated with New Hampshire school leadership to develop a K-12 curriculum focused on Franconia Notch cultural history. Students read folklore about the Notch and performed songs and plays about the region’s beauty. While the primary goal of this curriculum was to encourage children’s parents to donate to the campaign, many children also donated what little funds they had. Ultimately, school children gave over $1,000 to the campaign.

While the women of NHFWC participated in all of these efforts, perhaps their most critical contribution to the fundraising effort was their success in rallying women across the country to donate and to participate in the “Buy a Tree” campaign. They shared information on the campaign with the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, a national organization that united women’s clubs across the country. They also closely collaborated with women’s clubs around New England.

(New Hampshire Historical Society)

New England club members argued that preserving Franconia Notch was a way to highlight the natural beauty of the entire Northeast region. As one Massachusetts club leader wrote in a fundraising letter, “Every nature lover everywhere should become a center of influence in selling as many trees as possible.” Ultimately, the campaign received $7,000 in contributions from women’s clubs outside of the state.

By late 1928, the campaign had reached its $100,000 goal. The NHFWC raised $65,000 of those funds themselves. With over 15,000 contributors to the campaign, the Notch fundraiser was truly a grassroots effort that relied on small donations from ordinary people across the state and nation.

When Franconia Notch was dedicated as a state Forest Reservation and Memorial Park on Sept. 15, 1928, women had only been eligible to vote for eight years. The success of this grass-roots campaign demonstrates the unique ways that women participated actively in politics both before and after the enactment of the 19th amendment. Through a combination of creative fundraising efforts and alliances across organizations, women ensured their voices were heard in local, state, and federal government.

(Library of Congress)

Related Articles