Nutter was there to promote federal firearms legislation, including an assault rifle ban and a requirement that gun dealers conduct background checks to screen out criminals and mentally disturbed purchasers. But as he pointed out, most of the roughly 11,000 gun homicides in America in a given year aren’t mass killings perpetrated by deranged people using military-grade weapons. They usually involve only a few people at a time, often the product of gang feuding, personal quarrels or domestic disputes, carried out with ordinary handguns, not semi-automatic rifles. And even though gun murders have declined everywhere in recent years, the rates remain much higher in the urban cores of large metro areas.

Nationwide gun homicides have declined in recent years. But cities’ rates of gun deaths remain significantly higher than the rest of the country. The 63 counties that include the urban core of metro areas with a million or more people consistently record gun homicide rates about twice the rate of all other counties combined. The rate above represents the number of firearm-related homicides per 100,000 residents. (Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

The campaign for federal legislation died on the Senate floor that spring, and only a handful of states imposed major new limits on guns thereafter. That limited success by gun control advocates underscored a truth that Nutter and mayors all over the country understand perfectly well: Reducing the amount of gun violence in this country is now essentially a local issue, one that city leaders have to pursue on their home ground. But they have to pursue it carefully, avoiding outright bans on the possession or carrying of weapons. As a series of court decisions at various levels has made clear in the past few years, anything close to an outright gun ban is not going to survive judicial scrutiny.

In enacting new laws against gun violence, mayors and other civic leaders are challenging not only the courts but the strong pro-gun sentiment that exists in most state legislatures. In the past decade, Philadelphia alone has seen courts invalidate about a half-dozen local gun laws, including two bans on semi-automatic rifles, limits on the frequency of handgun purchases (one a month) and a requirement that gun owners be licensed before bringing a firearm into the city. Pennsylvania courts have held that only the legislature can pass laws pertaining to buying and owning a gun -- and the legislature has shown no interest in doing so.

As a result, anti-violence activists in Philadelphia and other cities in the country have had to get more creative in their push to reduce the number of guns on the streets. The approaches vary widely, from punishing reckless behavior by gun owners to rewarding businesses that take voluntary steps to prevent violent criminals from acquiring guns. What these approaches have in common, though, is a shift away from going after weapons themselves to a new focus on curtailing their unsafe use.

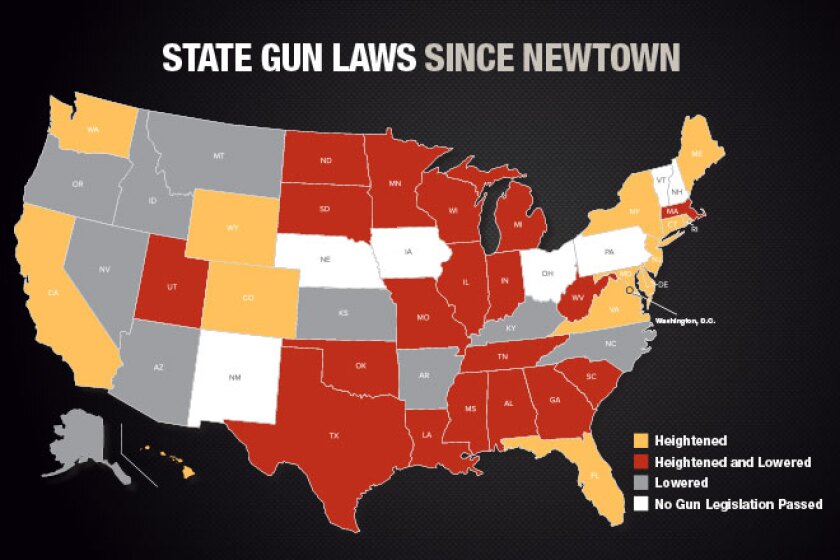

Forty-six states have passed more than 170 gun laws since the 2012 mass school shooting in Newtown, Conn. This map illustrates which states either heightened or lowered gun restrictions in that time. A handful of states pushed major gun control measures, banning rapid-fire rifles, limiting high-capacity magazines and expanding background checks on all gun sales. At the same time, some states sought to make gun ownership easier, preempting bans and other limits by cities and permitting people to carry guns in bars, churches and schools. Overall, 34 states heightened gun restrictions while 28 lowered them, with some passing a little of both. While the map treats all new gun laws as equal, some were broader in scope and more likely to affect gun owners.* (Source: Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence)

In Sunnyvale, Calif., for example, voters approved a measure designed to discourage straw gun purchases, in which one person buys a gun for someone else, by imposing reporting requirements on gun owners when their firearms are lost or stolen. Travis, Texas, decided to require that the only gun show in town make criminal background checks mandatory for all firearms sales. Dallas announced a new program -- already supported by state law, but not enforced -- that temporarily confiscates firearms from people on probation for domestic violence. And in Tucson, Ariz., the city council passed an ordinance that empowers police to request alcohol testing of anyone they suspect fired a gun while intoxicated.

The Tucson ordinance may invite legal challenges because Arizona has a state law preempting local measures against buying or owning guns. But that’s a debate welcomed by Councilman Steve Kozachik, sponsor of the alcohol-testing bill and another bill on reporting lost or stolen firearms. The state might have free rein on laws about purchase and ownership, he says, but the city ought to have some say on illegal and unsafe behavior. “If someone steals your gun, call the police. If you’re drunk, don’t use your weapon,” he says. “This is not anti-Second Amendment.”

While Tucson targets the behavior of gun owners, cities elsewhere want to change the behavior of gun businesses. Last year, the U.S. Conference of Mayors published a code of conduct for companies in municipal pension investment portfolios. Similarly, Philadelphia had about $15 million invested in businesses that sell guns and ammunition, including Smith and Wesson, Walmart and Sears. Its pension board required that those companies agree to conduct criminal background checks for all gun transactions and to ensure that their business partners -- mostly gun shows and gun dealers -- abide by the same stringent standard.

Two other public pension boards in Philadelphia adopted the same code of conduct for pension investing, and later last year mayors in Los Angeles and Chicago announced that they, too, would try to leverage their pension funds to force a change in the gun industry, focusing attention on gun manufacturers that still sold high-capacity magazines and semi-automatic rifles after mass shootings in 2012. Though the pension idea gained traction around the country, it may not yield the intended result. Last September, more than a dozen affected companies in Philadelphia’s portfolio refused to adopt the city’s gun principles, prompting its pension board to divest in all of them.

Nonetheless, the marketplace is an increasingly attractive arena for cities to apply gun policy without resorting to regulation. In January, Jersey City, N.J., Mayor Steven Fulop capitalized on his city police department’s need to buy roughly $350,000 in firearms and ammunition as a way to influence gun suppliers. To bid on the city police contract, the companies had to explain what they do with old weapons and how they comply with federal and state background check laws. As with local ordinances on lost or stolen firearms, Jersey City’s questions were meant to encourage the private sector to clamp down voluntarily on illegal and straw purchases, both of which are ways that criminals acquire guns.

Fulop wants the market-based approach to have ramifications beyond his own city, which is why he’s recruiting other mayors to ask the same questions. Nutter in Philadelphia and Seattle Mayor Ed Murray both say they may incorporate similar questions in their departments’ next big gun purchase. “We’ve got to build scale,” Fulop says. “The goal is by the end of this year to have enough cities involved that we could actually impact the dialogue through our pricing.”

Separate from Fulop’s efforts, 20 cities in Florida have formed a coalition that plans to impose new disclosure requirements in their bidding process for police contracts. Led by the nonprofit Arms with Ethics, the municipalities have committed to asking whether manufacturers run criminal background checks on their employees and what they do when they discover a retailer has been implicated in a gun crime. Members of the coalition can choose from a menu of suggested questions, but some say they’ll ask if gun businesses train their employees to identify straw purchasers so that they can avoid selling guns likely to end up at a crime scene. Others want to know if gun dealers maintain quarterly and annual inventories to see if any firearms are missing -- something that the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives can’t legally require. Taken together, says Casey Woods, the executive director of Arms with Ethics, the questions encourage “things that people think are already law, but aren’t.”

The market-based approach is too new to evaluate for impact, but critics question whether city police departments represent enough market share to change industry practices. Gun purchases by city police represent a small fraction of overall gun sales in a given year -- roughly 15 percent, according to IBISWorld, a market-research firm. Then again, police are disproportionately influential gun consumers, argues Gregory Gundlach, a marketing professor at the University of North Florida who first outlined the Jersey City-style approach in 2010. “The purchases are made in a static sense, but they’re also reoccurring,” Gundlach says. “Manufacturers realize that the lifetime economic value of law enforcement is pretty high because these sales aggregate over time.” Also, he adds, the guns that police choose to buy have spillover effects on the civilian market because average citizens often imitate police in their purchasing decisions.

Shortly after gun legislation stalled in Congress last year, a spate of local homicides prompted the city council in Richmond, Calif., to consider new municipal regulations. As recently as 2008, Richmond ranked as one of the nation’s 10 most violent cities of more than 100,000 residents. Almost all its homicides and half of its robberies involved guns. Nonetheless, Councilman Tom Butt, a self-described champion of gun control, voted against a resolution that would have studied options for new gun regulation. California already has some of the strictest gun laws in the country, he says, but “it’s not enough. Regardless of what kind of gun laws you have, people who really want to have a gun are going to find one.”

Seven years ago, Butt became an early supporter of a local anti-violence strategy that sidesteps guns entirely and focuses instead on the people who use them. “Illegal guns have always found their way into urban communities by some mechanism,” says DeVone Boggan, the director of neighborhood safety in the Richmond mayor’s office. “We need to find a way to get these young men not to pick these guns up, to develop the mindset that ‘I’m not going to deal with conflict by using a gun.’”

With the help of a data analyst from the police department and tips from street informants, Boggan’s office identifies young men who are suspected of being involved in a shooting -- but who have not been charged or convicted -- and invites them to join the city’s peace fellowship program. The perks of being a peace fellow include trips outside the city or even outside the country (destinations have included Cape Town and Dubai), plus financial rewards for participating longer than six months. While those benefits help recruit program participants, the real boon is the support services available to the city’s peace fellows. A team of older neighborhood residents -- often with a criminal past -- coaches the men on setting goals and mapping out the small, specific steps needed to accomplish everything from obtaining a driver’s license to applying for college. A caretaker accompanies the fellows through the maze of social services that they may need to stabilize their lives, from housing to drug addiction counseling. Finally, every fellow takes classes on anger management.

Boggan’s holistic approach to gun violence started in 2007. As of this past July, the program had recruited 68 peace fellows, with 25 completing the full 15 months. Fifty-seven had avoided being charged with a firearm assault since joining. All but three were still alive. The public image of the peace fellowship received a boost in January when the police department reported that 2013 saw the lowest number of annual homicides in three decades.

Since the program’s launch, other cities in California and around the country have called Boggan for advice on how to introduce a peace fellowship in their own jurisdictions. Public safety officials express excitement about the approach, he says, but by the end of the discussion they’re pessimistic about replicating the fellowship. “The challenge,” Boggan says, “is being able to go back home and sell this idea of providing positive resources to individuals who have often committed heinous crimes.”

Indeed, it’s an open question whether other cities will want to use a Richmond-style program as a road map for tackling gun violence. One of the model’s biggest assets, says Angela Wolf, a community psychologist studying the program, is long-term intensive mentoring that extends beyond the fellows’ graduation. At least two years later, former fellows still call their mentors for advice about how to handle a conflict or career decision. The model requires a major investment of time and money to turn around the lives of a small number of residents.

Nonetheless, Boggan argues that supporting a few violent residents with human resources might be the most efficient use of tax dollars. When the city hired Boggan in 2007, it faced a $24 million structural deficit, much of it driven by expenditures of $6 million per year for law enforcement. Like most cities, Richmond had responded to spikes in violent crime by hiring more officers and putting violent people in jail. That was expensive, and it wasn’t doing much to solve the problem. “If you look at most cities where the public safety budget is going through the roof, it’s justified by the actions of a relatively small group of men doing a lot of damage,”

Boggan says. “We have to identify alternative solutions that are much more responsive.”

Updated: After the above map was published, Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick signed a major gun law that heightened restrictions in several ways. The law gives police chiefs new discretion in deciding whether to issue firearm identification cards for people purchasing a shotgun or rifle. The law also expanded background checks to all private gun sales and increased penalties for gun crimes. The map was updated to reflect this change.