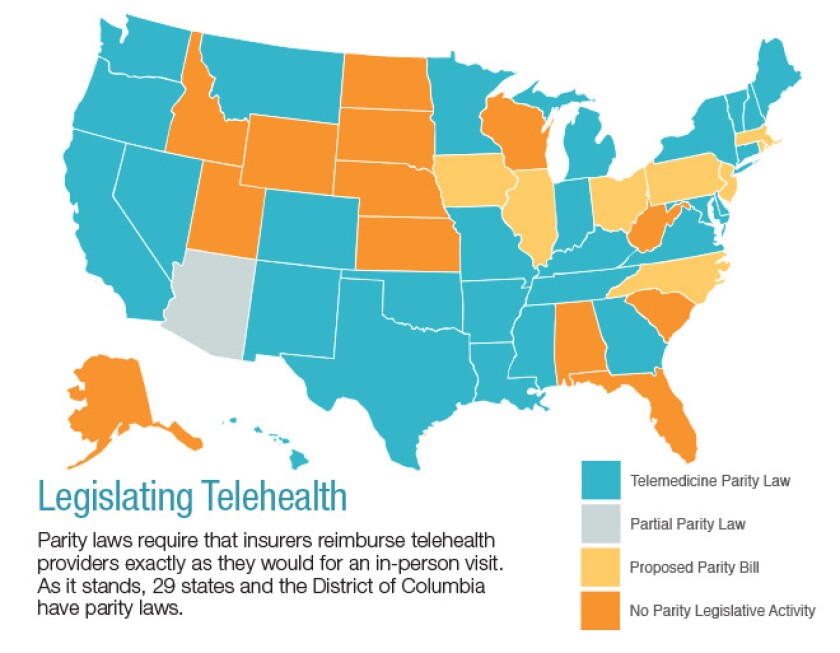

States have been playing catch-up. As recently as 2011, only 11 states had telehealth parity laws, which require that insurers reimburse telehealth providers exactly as they would for an in-person visit. Today, 29 states and the District of Columbia have parity laws. In those jurisdictions, if a patient with a sore throat wants to confirm she has a strep infection and receive a prescription for antibiotics, it makes no difference to insurance companies whether the visit occurs over the computer or in an office. Forty-eight state Medicaid programs (every state but Connecticut and Rhode Island) offer some form of coverage for telemedicine. Congress is expected to take up legislation this year that would expand telehealth coverage for Medicare enrollees.

More than 200 telemedicine bills were introduced in state legislatures in 2015. Not all of them passed, but it has “given an indication that the time has come to have [the telemedicine] conversation,” says Jonathan Linkous, CEO of the American Telemedicine Association.

Despite the momentum, there are still plenty of gaps and question marks when it comes to telehealth policy. The 21 states without a parity law aren’t uniformly liberal or conservative. Kansas, South Carolina and Utah don’t have one, but neither do Illinois or Pennsylvania. Massachusetts, a state known for progressive health-care policies, doesn’t have a parity law. It currently only covers telemedicine under Medicaid with certain managed care plans, and not for fee-for-service payments.

Even among states that do have parity laws, the patchwork of policies can vary widely from one state to the next. Texas, for example, requires insurers to cover telehealth, but it mandates that a patient’s first appointment with a new doctor must be an in-person visit. Within Medicaid programs, about half of the states require that a patient be in a medical facility for telehealth appointments, rather than at home. The differences among states can be frustrating for telemedicine providers. Kofi Jones, vice president of public relations and government affairs for the telehealth company American Well, says she has 30 binders in her office filled with state-by-state regulations and legislation. “I’m waiting for the day when parity laws are uniform across the country,” she says. “I suspect it’ll continue to be a slog, but when that day comes, I’m having a binder-burning party.”

Traditional health-care providers can be slow to integrate new technology. After all, almost half of doctor’s offices polled in 2013 still used paper records, according to a survey from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Other recent surveys have found that only 2 percent of patients nationwide have access to video visits with their primary care physician. Less than half -- 45 percent -- even receive a traditional phone appointment reminder.

But the explosion of born-online health-care services is fueling a rising consumer demand for more telehealth options. Telemedicine advocates see it as a way to cut down emergency room visits and increase health-care access for rural patients. Many in the medical community, however, maintain strong concerns about patient privacy and overall quality of care. As states move toward more inclusive telehealth policies, they must confront those issues along with a more basic question: Just how good is the medical care you get over the phone?

Florida is the nation’s third most populous state. And with its large population of seasonal snowbirds and transplanted retirees, Florida presumably has a lot of people who would like to seek medical help from their doctor back home. But the state, which doesn’t have a parity law, is like “the Wild West” when it comes to telehealth, says Christian Caballero of the Telehealth Association of Florida, a trade group formed last year to push for parity legislation in the state. The association in July received a planning grant from the state Health Resources and Services Administration to implement telehealth options in north Florida, which is more rural and underserved than other parts of the state. “When you give people health care on the front end, that just drives down the overall costs of health care,” says Caballero. “Now it’s up to us to give people in underserved areas those options.”

Florida lawmakers have considered telehealth bills in recent years, but none of the measures have become law. Advocates were optimistic about a proposed telemedicine bill last year, because unlike previous proposals, it stripped out language that would have required Medicaid to reimburse providers at the same rate as for in-person visits. But the bill died in committee.

The difficulty in passing legislation in Florida echoes broader conversations about telemedicine across the country. In many cases, doctors have urged caution when it comes to adopting new technologies. The American Optometric Association, for instance, has come out hard against online eye exams, calling them a “substandard model of care.” The American Medical Association (AMA) is more open to telemedicine but has taken a cautious approach. The group released recommended guidelines for telehealth coverage and payment in 2014, but held off on releasing an ethics policy in November after concerns were raised that the draft proposed wasn’t thorough enough. “This is something I’m passionate about, and I’ve been engaged with it for a while,” says AMA board member Jack Resnick. “But we need to make sure that we’re doing it right -- telehealth can’t just become another silo in health care. It’s important to us that a physician using telehealth practices understands a patient’s full medical history and is able to coordinate that care with their other providers.”

The problem, Resnick says, is that telehealth appointments are often “one-off visits, where information isn’t relayed back to that person’s primary care provider.” Mobile telemedicine apps may or may not catalog a patient’s health data from one session to the next; regardless, it’s up to the patient whether she chooses to share that information with her primary physician. “That’s bad care,” says Resnick, “and a potential hazard of telemedicine.”

SOURCE: American Telemedicine Association

There’s also the issue of privacy when it comes to patient data. Many medical professionals worry about the potential for hackers to access and expose patients’ sensitive medical information. Some private companies, including American Well, Doxy.me and Teladoc, offer HIPAA-compliant interfaces for physicians to use -- at no cost, in some cases -- which the companies say are safe and reliable ways to protect information. The concern over hackers is legitimate but overblown, says Robert Pearl, chairman of the Council of Accountable Physician Practices. And patients aren’t likely to care anyway: “If someone were to hack into your health and financial information, most people would be more freaked out over financial information,” he says. “Yet that possibility doesn’t stop people from online banking and ordering from Amazon.”

Cross-state licensure is another big issue that has stymied telehealth expansion in the past: How can a physician licensed in Virginia treat a patient who lives in New Mexico? But that, too, is changing rapidly. The Interstate Medical Licensure Compact, an agreement initiated by the Federation of State Medical Boards, provides an expedited way for doctors to have their licenses recognized by multiple states. Since the compact was introduced in late 2014, a dozen states have signed on -- Wisconsin became the 12th in December -- and bills are pending in at least nine more states. It’s easy to imagine that in a very short time, a doctor who’s licensed to practice anywhere in the country will be licensed to practice everywhere in the country.

Telehealth advocates don’t imagine e-health ever fully replacing face-to-face interactions between patients and physicians. Instead, the idea is for video chats, texts and phone calls to become more seamlessly integrated into the existing health-care system. Linkous, the American Telemedicine Association CEO, has been with the group since it was founded in 1993, when telemedicine mostly involved primary care physicians in rural areas communicating in real-time with a specialist in the next big city. As technology has advanced over the past 20 years, attitudes and expectations have changed too. That will continue to happen, Linkous says. “Who nowadays would ever use a bank that makes you come in to a branch to access your money? Five years from now the question will be, ‘Who is going to go to a doctor’s office that makes you come in every single time you have the sniffles?’”