Arturo Carrillo, the mental health program manager at Saint Anthony, says there’s been a near-constant waiting list since he started as an intern in 2005. The list is longer in 2018 than it’s ever been. This is despite a widespread belief that Hispanics and African-Americans are less likely than other groups to seek out mental health treatment because of a widely felt stigma against it.

Despite its name and size, the 151-bed facility feels more like a community health clinic than a sprawling city hospital. Spanish is often spoken when people check in at the front desk. On one recent morning, a child played with an adult in the waiting area, while a couple in the reception room waited for medication-assisted treatment, an FDA-described “whole person” approach to weaning people off substance abuse.

Two waves appear to have contributed to the exceptionally long waiting list for mental health services at Saint Anthony. The most recent came in the aftermath of the 2016 presidential election, when Spanish-speaking communities reported growing anxiety as a result of the new zero-tolerance immigration policies. But the much bigger wave came a few years earlier, in 2012, after Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s administration shuttered half a dozen city-run mental health clinics. Two of those clinics were in the low-income areas that Saint Anthony serves. “The Woodlawn clinic was a crucial clinic for the African-American community in need,” Carrillo says. “The Back of the Yards clinic had Spanish-speaking psychiatry services. It’s the degradation of many layers of the social safety net. That’s not just a Chicago problem, but in Chicago there’s been an intentional disregard for investment in these areas.”

In 2011, Chicago had 12 community mental health clinics. Now it has five. Local officials cite both cuts in state funding and a consolidation plan from the city that aimed at shifting patients to private mental health centers. Protesters sat vigil day and night outside the clinics in the months leading up to their closure, arguing that the patients wouldn’t have anywhere to go. It didn’t make a difference: By the spring of 2012, Chicago was down to six city-run clinics. That number was reduced to five after one was privatized in 2016.

Five years after the closure decision, mental health advocates and activists say traditionally underserved areas are still reeling from the double budget cuts from the city and state. “It was devastating and frankly unnecessary,” says Jaleel Abdul-Adil, co-director of the Urban Youth Trauma Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “I know Chicago has money it could have spent on more mental health resources, and ironically we’re more than happy to spend that money on policing and prisons. It shows a real lack of vision for what wellness looks like for urban youth and families.”

City officials dispute the argument that the 2012 decisions had a cascading impact on the city’s treatment of mental illness. Health Commissioner Julie Morita says the city was responding to state action in the best way possible. The reduction in state assistance, she says, “resulted in us closing clinics that we knew had skeletal crews and not that many people using them. People look to those closures to have a reason to blame Chicago’s problems on, but it’s a bit of a scapegoat.”

These are arguments that have been going on for half a century, and in many places besides Chicago. In the early 1960s, the Kennedy administration advocated closing most large public mental hospitals in the hope that patients would be better served by community clinics, including private ones. Within a short time, this policy drastically reduced the number of inmates in residential treatment throughout the country. Critics have argued ever since that private and nonprofit facilities aren’t publicly accountable like publicly funded clinics, and that they constantly have to battle crippling budget and capacity restraints.

In any case, the goal of expanded community-based treatment never came close to being fulfilled, in Chicago or anywhere else. The nonprofit Community Counseling Centers of Chicago (C4) was seen as the primary partner to absorb patients dismissed from hospitals, but by 2015 C4 was on the verge of closing. An 11th-hour deal with Cook County allowed its centers to remain open, but at less than full capability.

There isn’t data showing where patients went after the Chicago clinics closed in 2012 -- whether they were able to find care elsewhere or simply fell off the radar. Mental health advocates in Chicago insist many of them stopped receiving care entirely. “No one has been able to argue that they reinvested comparable dollars into a better system,” says Paul Gionfriddo, CEO of Mental Health America, a nonprofit focused on community-based mental health care. “Illinois usually ranks around middle of the pack for mental health access, and I believe what’s pulling it down is Chicago.”

The Chicago chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reported in 2015 that the use of hospital emergency rooms for mental health needs had already been increasing in the city prior to the 2012 cutbacks. Chicago Public Radio reported that from 2009 to 2013, there was a 37 percent jump in the number of people discharged from emergency rooms who had gone there for psychiatric treatment. The biggest jump came in 2012. “These cuts,” NAMI has claimed, “have made it impossible for service providers to build the infrastructure required to support the need of those living with mental health conditions.”

NAMI Chicago’s executive director, Alexa James, puts things a little more bluntly. “We are a very sick city,” she says. “We are in an absolute crisis. The people we’re interfacing with today are sicker than we’ve ever seen, and younger.”

Saint Anthony Hospital on Chicago’s West Side has a yearlong waiting list for mental health services. (AP)

All over the United States, mental health providers are struggling to find new ways to make treatment more accessible. The Affordable Care Act made a commitment to cover mental health on par with other forms of care, but the provision has not been enforced. Still, with more Americans insured than ever before -- and more stakeholders shifting from a fee-for-service model to one that incentivizes healthy behavior -- the health-care industry is moving toward a system that treats people more holistically, taking social determinants of health into account. But it is far from achieving that goal. And money continues to be an intractable problem.

These strains are present in Chicago. In addition to the cuts from the city, Illinois has recently emerged from a two-year-long budget impasse, in which state-funded Medicaid mental health services were a primary casualty, with some mental health services going unfunded for months. At the height of the state’s budget crisis, Screening, Assessment and Support Services (SASS), a state-funded crisis response program, was able to offer its services only one day a week. Thresholds, a nonprofit institution that is one of the largest mental health providers in the state, found in 2013, before the worst of the budget impasse, that emergency mental health hospitalizations due to state spending budget cuts had already cost Illinois $18 million.

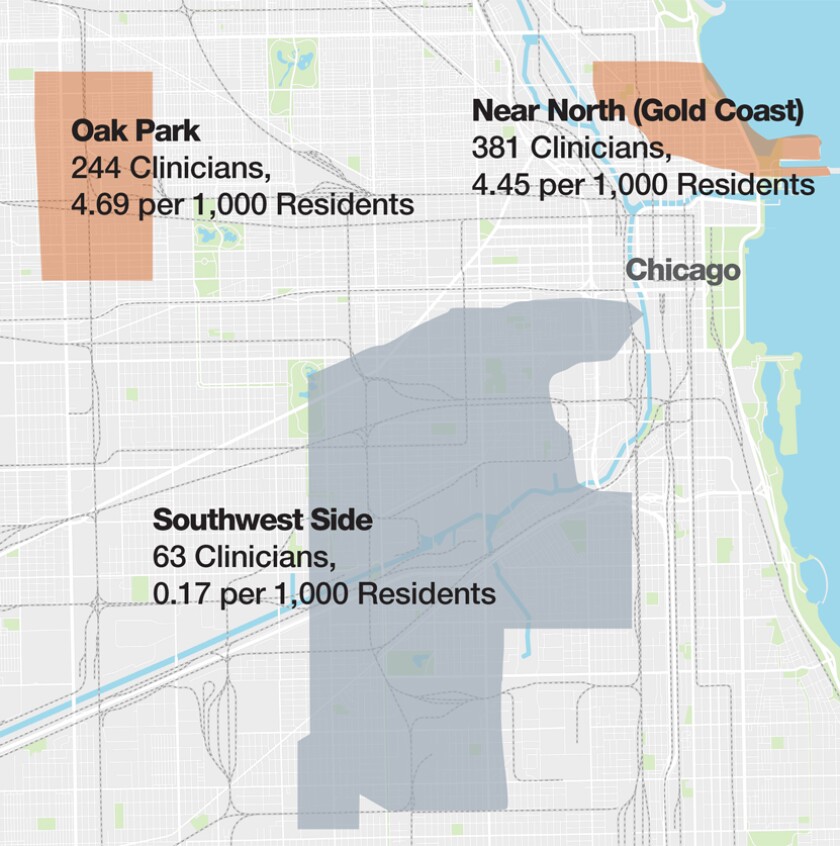

This year, Carrillo of Saint Anthony was the lead researcher on a report by the Collaborative for Community Wellness, a group of 22 community organizations that came together to mine mental health data for Chicago’s Southwest Side. The report paints a picture of great need and seriously inadequate resources. Half of the respondents to the group’s survey reported depressive symptoms. Thirty-six percent showed symptoms of anxiety, and nearly that many were diagnosed with trauma. Eighty percent of respondents said they were interested in some form of counseling. To serve those populations, there are currently 63 mental health clinicians on the entire Southwest Side of Chicago, which works out to 0.17 therapists per 1,000 residents. On the Gold Coast, an affluent Near North Side neighborhood, there are 381 mental health care providers, or 4.45 per 1,000 residents.

Treatment options are limited for low-income and uninsured residents on Chicago’s Southwest Side. Meanwhile, there are plenty of clinicians available in more affluent neighborhoods in the Chicago area. (Collaborative for Community Wellness)

It is not easy to compare mental health access in different cities, but some available data suggests Chicago has a worse-than-average problem. There are 15 publicly funded mental health clinics in East Los Angeles, a low-income area of that city. The state of New York lists 73 mental health programs in the Bronx alone.

The only consistently funded mental health center in the Chicago area is the Cook County Jail. Sheriff Tom Dart has implemented numerous measures making it easier for people in the jail to get mental health care. Dart believes about half of the women who enter the jail are mentally ill, as are about a third of the men. Inmates diagnosed with mental illness are separated out and offered care on par with what they’d get in a hospital. When those with mental illnesses are released from the jail, a nearby clinic run by the University of Chicago offers them a soft landing for a few days before they return to outside life.

Though mental health advocates in the city are grateful for Dart’s efforts, there is a sense of frustration that so much of the responsibility for taking care of Chicago’s most vulnerable has fallen to a jail. “We should never accept the premise that a jail is a mental health facility,” says Heather O’Donnell, senior vice president of advocacy and public policy at Thresholds.

Despite the budget turmoil throughout the city and state, Thresholds has been able to grow in recent years, in part because of an increase in federal funding, as well as private donors. Still, says CEO Mark Ishaug, “there are not many other places harder than Illinois to do this work.” During the worst of the budget impasse, the organization had to depend on a local bank to provide a line of credit so it wouldn’t miss its payroll. “There is all of this lost opportunity to serve people before they become so sick,” he says. “It’s not just the state, because it feels like the private insurance system has colluded on this. They do not provide coverage for the kinds of services that the people who we serve need.”

Surprisingly, though, Ishaug insists he’s optimistic. He points to recent wins in the statehouse that may show a changing attitude in policy. There’s a newly created mental health committee in the legislature. During the last session, Gov. Bruce Rauner signed several mental health bills, including one that would seek federal approval for Medicaid to cover community-based screenings and interventions for youth and adolescents.

Earlier this year, the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved a waiver for Illinois that gives the state authority to use $2 billion over five years for 10 pilot programs. The waiver is meant to treat opioid addiction, but there will be a large behavioral health component as well.

In the meantime, Health Commissioner Morita says the city has been working and is continuing to work with other health-care providers to expand care where it’s needed. “By not just focusing on the delivery of care,” she says, “we’re able to work as gap-fillers in the city,” by which she means that they now focus on helping clinics expand care where it is lacking. “I want to go to a clinic that offers comprehensive, whole person health.”

Though there is a bit of momentum, particularly on the state level, advocates worry that the staying power necessary to create genuine change does not exist. “I’m hopeful that we’re fed up with current systems,” NAMI’s James says. “But what I’m frustrated with is that it’s not meaningful reform and it’s mostly sparkly press conferences. Creating reform within mental health has to get messy. It really stems from reimbursement issues and capacity building and non-sexy things like that.”