Every year, millions of American workers enter a gray zone between unemployment and a traditional, stable 9-to-5 job. Wingham Rowan calls them “irregular workers.” In a recent report for the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Rowan defined irregulars as those who work outside the home with no contractual expectation of regular hours or income. “This is still an under-the-radar issue,” he says. “It’s not reflected in the official data, but indicator after indicator says [more] people are beginning to work irregularly.”

Though irregular work has implications across all levels of government, state and local workforce development boards may be the most affected. These boards, which receive federal, state and local funding, match job seekers with employers and training. But the boards are oriented around full-time positions with a single employer. If a large number of employment opportunities don’t fit that paradigm, workforce boards can have a hard time functioning.

Several years ago, a workforce board director in Long Beach, Calif., Nick Schultz, commissioned a local labor market study. Schultz was worried about the impact of a Boeing plant closure that would affect nearly 2,000 employees; he hoped the study would provide a road map for matching in-demand jobs with recently laid-off residents. But the study’s most significant finding wasn’t in the official data on occupations and wages. “It became apparent to us,” Schultz says, “that there were just a lot of folks, based on cost of living, who couldn’t possibly be making it with their payroll job on the record.” His agency concluded that more than a quarter of local workers earned money from temporary part-time jobs -- often multiple arrangements simultaneously -- that weren’t captured in the official employment data. In some cases, people were also earning unreported income.

Just knowing that information makes Long Beach an exception. Most places have no idea how big a chunk of their local workforce is participating in irregular work. At the moment, analysts such as Rowan are cobbling together statistics from government and nonprofit surveys that point to a rapidly growing nontraditional workforce, even if the exact labels and figures don’t always line up.

About one-third of U.S. workers are not in permanent jobs with a traditional employer-employee relationship, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office. The Rand Corp. estimates the number of “contingent” workers to be lower, at about 16 percent, but that’s up from 10 percent in 2005. Perhaps most provocatively, Rand’s research suggests that all of the net growth in the nation’s jobs during the previous decade came from contingent work arrangements.

Those contingent jobs often involve schedules that change from week to week, or day to day, but “the irregularity is creeping into a lot of regular jobs, too,” says Lonnie Golden, an economist at Penn State University. “If you’re a restaurant worker, you used to be able to get a week or two of advance notice. Now you might get a day or two.” In a report for the Economic Policy Institute, Golden found that about 17 percent of hourly workers have “unstable work shift schedules,” which includes rotating, on-call and irregular shifts. Even more people, roughly 41 percent of hourly workers, receive their schedules no more than a week in advance, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The gig economy, based on Uber, TaskRabbit, Postmates and countless other platforms, represents one small slice of the new irregular marketplace. But legacy retail and fast-food companies are a bigger source of these unpredictable part-time positions. Using ever-smarter computer systems, managers can now schedule and summon workers based on fluctuating demand for staffing on a daily, if not hourly, basis. Though proponents of irregular work tout its flexibility and potential to maximize staffing efficiency, it’s hard to deny the cost to workers. Three years ago, The New York Times profiled a single mother working at Starbucks who had to juggle child care, bus travel and unpredictable shifts, which never reached 40 hours and fluctuated on a weekly basis. Starbucks wasn’t alone. The Times coverage pointed to a more widespread problem across many U.S. chains. Companies send workers home when sales are slow and ask workers to be on-call or have “open availability” in case they’re needed to come in unexpectedly.

Besides unpredictable schedules, irregular work usually comes without the benefits typically associated with a traditional job. At tech startups, workers are often subject to arbitrary and unexpected pay cuts to boost the company profits. Investors can also bring the company’s existence to an abrupt end, creating an even more traumatic situation for part-time workers.

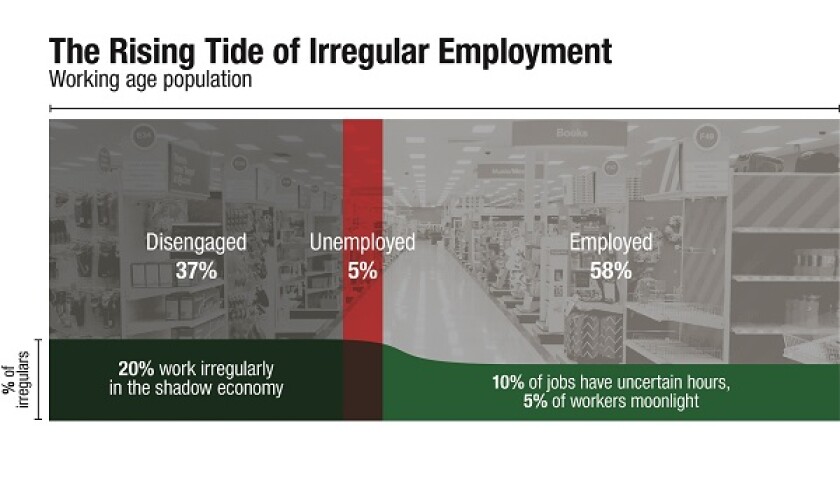

Millions of Americans work in a gray zone between unemployment and a traditional 9-to-5 job. SOURCE: Annie E. Casey Foundation

Rowan’s report on irregular work, which gathered data from 25 workforce boards across the U.S., suggests that workforce directors aren’t sure what role they should play, if any, in matching job seekers with these kinds of jobs. Federal law sets performance targets for state and local boards based on job placement, job retention and gains in both skills and earnings. Their data collection systems are equipped to handle a laid-off manufacturing worker looking to change careers, but not an Uber driver who just got kicked off the app. “Most of our policies are not applicable to a gig economy conversation,” says Sarah Blusiewicz, an assistant director in Rhode Island’s Division of Workforce Development Services. “It is something that everyone is grappling with at a national level.”

One proponent of government matching job seekers with irregular work is Lael Brainard, a member of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. At a conference last year on the evolution of work, Brainard said that the wide availability of nontraditional jobs might soften the blow of a future recession, giving laid-off workers temporary ways to make money. Even now, with unemployment at its lowest point in more than a decade, she believes remaining job seekers could benefit from temporary, part-time work that doesn’t require advanced skills or an extensive work history. At the same time, Brainard says, policymakers have to find ways of protecting the irregulars, either through financial savings vehicles or portable benefits, when the companies fail to provide them.

Labor rights advocates insist that low-skill job seekers are taking irregular jobs not because they want them, but because they lack access to stable, higher-paying positions. One recent study found that 37 percent of freelancers pursued contingent work out of necessity, not choice. That’s a concern for Maria Flynn, CEO of Jobs for the Future, a national nonprofit focused on the economic opportunities of low-income young people. “As the nature of work continues to change,” Flynn says, “how do we ensure that workers who are already being left behind don’t become even more left behind?”

Some governments are beginning to protect the welfare of irregular workers. One way to do that is to pass so-called fair scheduling acts, laws requiring employers to provide more predictable hours for part-time employees, or foot the bill when they don’t. One of the latest cities to do so is Seattle. Last year, about 30 percent of surveyed workers in Seattle indicated that scheduling created hardships for them. About the same percentage said they worked exhausting “clopening” shifts, where they would close and then open the store, often because it was the only way to get enough hours at their primary job.

Based on the survey’s findings, the city passed a “Secure Scheduling” ordinance, which requires retail and fast-food establishments above a certain size to post schedules two weeks in advance and pay workers extra if they have to pick up or lose hours after the schedule has been set. The measure still lets employees pick up hours and swap shifts, but in those situations, they initiate the schedule changes, not the employer. City Councilmember Lisa Herbold, a co-sponsor, says her concern is that innovations in scheduling technology might worsen working conditions in the absence of regulation. “I don’t want the brave new world of the gig economy to turn into a dystopian future,” she says, “where a large portion of our workforce is sitting at computers, competing against hundreds of people for the privilege of getting an hour-long shift.”

In recent years, a dozen states and a few cities have passed some kind of worker protections around scheduling. In June, the Oregon Legislature enacted what is considered the most comprehensive statewide fair scheduling law. The law affects retail, food service and hospitality companies with at least 500 employees worldwide. In addition to requiring two weeks of advanced notice on schedules, Oregon now requires “reporting pay,” meaning companies have to pay employees who report to work as scheduled but get sent home before completing their shifts. The law provides a right to rest between consecutive shifts and a right to express scheduling preferences without retaliation from the employer.

Fair scheduling is one of a series of recent worker protection ideas embraced by the political left. Since the recession, states and localities controlled by Democratic administrations have enacted higher minimum wages, guaranteed paid sick days and penalties for refusing to compensate overtime work. “At its core, it’s about pay not keeping up with aspirations, with expectations, with inflation,” says Golden, the Penn State economist. Irregular scheduling also means irregular pay, which is something labor advocates are trying to address through the scheduling acts. But the laws are also about giving workers more control over their time. Or, as Golden puts it, “who gets to determine when you work?”

Localities are looking to enact other kinds of labor protections for people engaged in nontraditional work. In May, for example, New York City passed the Freelance Isn’t Free Act, which requires hiring parties to pay freelancers within 30 days of when work is completed. The law is supposed to address late payments and nonpayments, which -- along with unpredictable hours -- are common complaints among contingent workers.

As scheduling technology has improved, employers like Target can summon or dismiss employees based on fluctuating demand. (Flickr/Stephen Downes)

But increased regulation is the wrong policy response, say Rowan and others. Some economists theorize that many American workers migrated to an underground economy during the last recession and, thanks to the weak recovery, are still resorting to off-the-books work. Strict schedule rules might accelerate that trend. “The danger,” Rowan says, “is that you make hiring for cash under the table more and more attractive by putting these constraints on employers.”

At the same time that fair scheduling is being advanced in some states, others are rolling protections back. Georgia, Iowa, Arkansas and Tennessee already have laws on the books blocking any attempt by their local governments to pass rules around predictable scheduling. Allison Gerber, a senior associate with the Casey Foundation, worries that a new wave of local regulations around scheduling will only invite a backlash of state preemption laws, as has happened with minimum wage laws in recent years.

One alternative to fair scheduling laws is the creation of a new public online marketplace, an idea put forward in the Casey Foundation report. Online job banks run by workforce development boards already exist in most states, but they generally lack the capacity to respond to immediate demands for short-term work. More sophisticated marketplaces could empower job seekers by giving them a single place to look for work across many irregular, part-time opportunities. Workers could quickly compare their options at a given time and pick what’s best for them. Employers could select the best candidates based on when workers were available and what skills or credentials they have. While workforce board counselors wouldn’t want to send everybody to jobs with unpredictable hours and no benefits, “the answer is about fit,” Gerber says. “Some folks need to build a work history, so this might be the right opportunity now.”

Workforce boards are not getting much encouragement from the federal government. Two years ago, when Congress replaced the law that funds workforce boards across the country, it tied funding to performance targets designed around traditional full-time work with a single employer. When local boards match more job seekers with a steady flow of irregular positions, even if the aggregate work reaches 40 hours a week, they’re unlikely to get credit under federal reporting requirements.

Nonetheless, one place has decided to take the plunge: Long Beach. The city’s workforce board this month will launch a year-long effort to collect information on irregular workers and their employers. Schultz, the director in Long Beach, hopes it will help him establish the first local public marketplace for irregular and gig work in the United States. Several philanthropic groups, including the Casey Foundation, are funding the experiment. A handful of workforce directors in other parts of California, as well as several states, are in regular conversations with Long Beach about the project, and how it might provide a template for other public marketplaces. “We’re not the only people thinking about it,” Schultz says. “They’re watching closely.”

*CORRECTION: A previous version of this story misstated Maria Flynn and Allison Gerber's job titles.