Over the years, however, CDBG funding has sharply declined and the number of places taking from the shrinking pot has risen. The result, critics say, is a weakened program that makes little impact and sometimes aids wealthier communities that don't need the help. President Obama tried to shrink and redesign the program. Now President Trump wants to eliminate it altogether.

But a new report argues the program could boost its impact by adopting a simple mantra: less is more.

In a policy brief published last week, the Urban Institute recommends changing the eligibility rules so that CDBG funding would be spread across fewer communities, providing greater assistance to low- and moderate-income neighborhoods. Overall funding should go up as well, the group argues, but only if the money is better targeted.

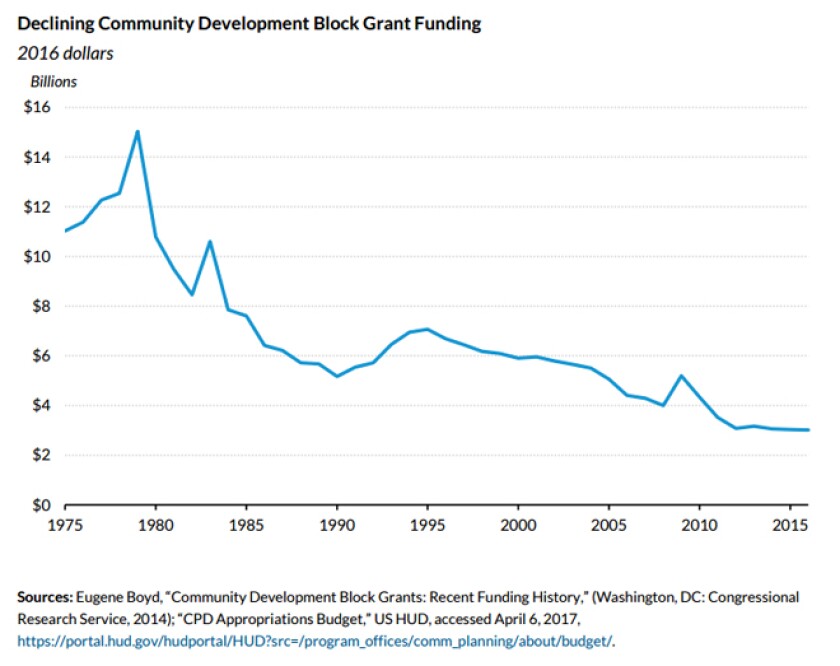

When adjusting for inflation, CDBG once provided as much as $15 billion a year to local governments. Today, the amount hovers around $3 billion.

Meanwhile, the number of communities that meet the program's eligibility criteria has also increased, by 86 percent since 1980.

(Source: The Urban Institute)

To a large extent, the Urban Institute's recommendations echo the Obama administration's budget proposals. After a review of CDBG in 2013, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development called for legislative changes to reduce the number of small grantees and to better target funding to areas with the greatest need. Congress largely ignored the proposals, but they always riled up mayors and county officials.

The national groups that represent CDBG recipients disagreed with the Obama-era suggestions and won't back the recommendations outlined by the Urban Institute either.

"We at this point are not supportive of any proposal to limit the amount of grantees," says Daria Daniel, a lobbyist with the National Association of Counties (NACo). "Our goal is to increase the funding so that it can increase for all."

For its part, the Urban Institute is advocating for more CDBG funding along with its recommended reforms. The authors also argue that the federal government should set aside some money for studying the program's impact.

Trump’s budget director, Mick Mulvaney, told reporters in March it was time to eliminate CDBG because there's no proof that it has met its original goals of helping lower-income residents, reducing blight and addressing imminent health and safety threats.

“We can't spend money on programs just because they sound good,” Mulvaney said.

But Brett Theodos, a co-author of the Urban Institute report, points out that the program hasn't been formally studied in almost two decades.

“It does seem a little odd when someone in the current administration has said there’s no evidence that the program is working. There’s no evidence it’s not working, either,” he says.

In one sense, the block grants already produce visible results. Many communities use the money to pay for building and maintaining infrastructure, from hospitals to homeless shelters to sewer lines. They also report the estimated number of people served by a specific project or service. But critics question whether the money is spent as efficiently and effectively as it could be, and that's where better measurement and independent evaluations could help.

NACo's Daniel says the beauty of CDBG is its flexibility, both in terms of potential uses and the kind of community that receives funding.

"It doesn’t focus on just one area. It benefits urban, suburban and rural counties," she says. "We think it is working. We just need to get that story out more."