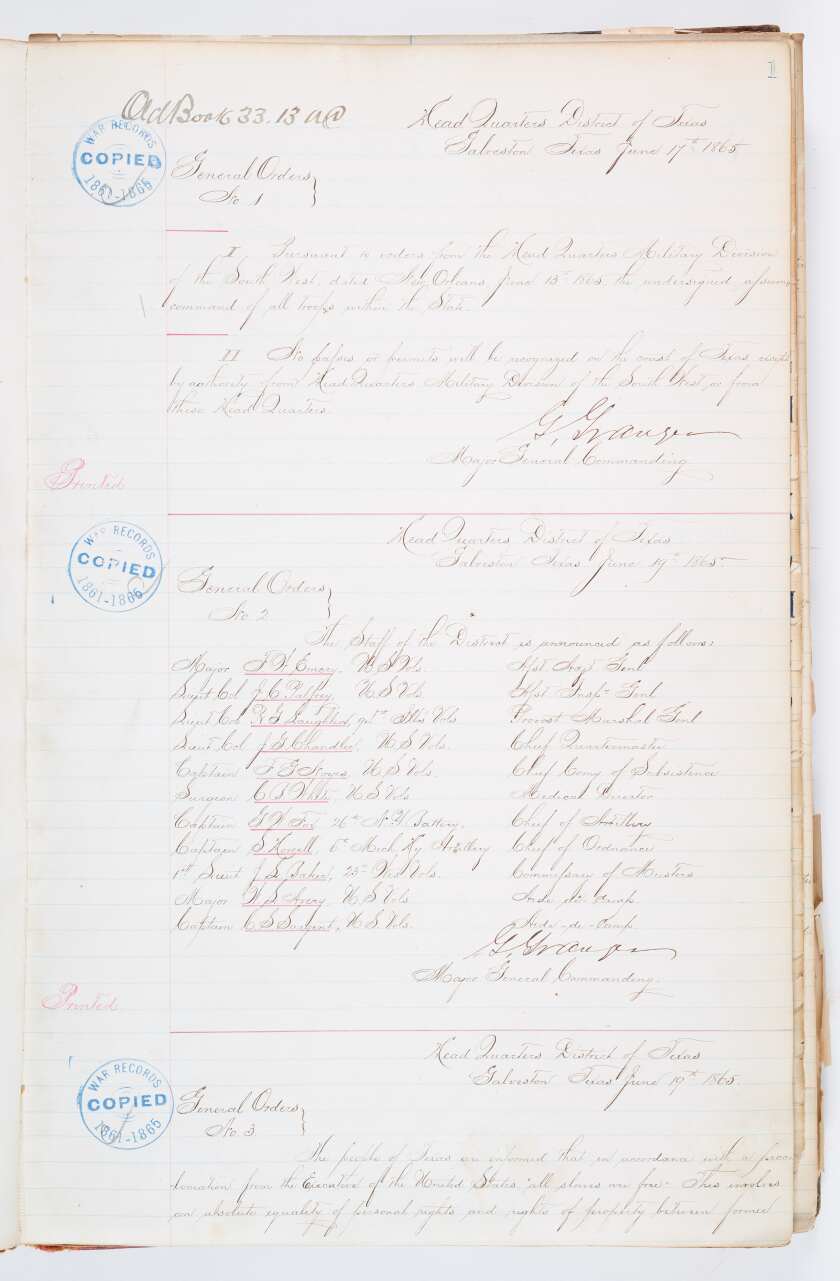

But word of the proclamation during the war traveled slowly, especially in a remote state like Texas. Many slaveowners simply defied the proclamation, forcing thousands of enslaved people into continual bondage. But on that June day in 1865, the reality that slavery had ended officially reached what had been the westernmost state in the Confederacy.

For over 150 years, Juneteenth – also known as Liberation Day, Emancipation Day or Jubilee Day – has been celebrated by Black men and women in Texas since Granger’s proclamation. Former slaves within the state developed grassroots-level commemorations and celebrated throughout the 19th century by hosting religious services, reciting the Emancipation Proclamation, and singing songs and hymns. Some Juneteenth events were overtly political, as organizers held events to teach Black citizens about their newfound voting rights. But the celebrations were also festive, social gatherings: people would play games, share food and drink, and attend rodeos and dances. Towns and cities held ornate parades replete with floats representing the ideals of liberty and freedom.

Some white Texans sought to suppress these celebrations, as Juneteenth countered the Southern Lost Cause narrative that romanticized slaveholding culture and the Confederacy. They employed segregationist laws to prevent Black locals from hosting celebrations in state parks and other public spaces.

During World War I, thousands of Black Texans began moving north and west to find industrial jobs and escape the segregationist laws and economic difficulties plaguing them in the South. This period became known as the Great Migration, with Black people taking the Juneteenth holiday with them to cities across the country.

By the 1920s, the now nationally known holiday had become increasingly commercialized and associated with mass entertainment. Department stores sold festive outfits specifically for Juneteenth, and commemorative carnivals held countless rides and games. But these celebrations slowly receded by World War II, in part because Black Americans became disillusioned by continued inequalities and were less inclined to celebrate their holiday.

By the late 1970s, Texas became the first state to make June 19 an official state holiday, although they simultaneously recommitted to celebrating Jan. 19 as Confederate Heroes Day. Dozens of other states eventually declared Juneteenth a state holiday, and various figures advocated for the federal government to nationalize the holiday.

This advocacy reached a crescendo in 2020, when Juneteenth celebrations included protests for police reform, particularly after the death of former Texas resident George Floyd. The following year, the federal government made the date the newest national holiday.

June 19, 1865 did not, of course, lead to immediate equality for Black Americans, and the 2020 protests demonstrate that social justice remains an unfulfilled ideal for many. The unique ways that the holiday has been celebrated over time, as well as the varied iterations of the holiday at the local, state and national level, reflect the evolving meanings of freedom and equality in America.

You can also hear more of Clay Jenkinson’s views on American history and the humanities on his long-running nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. He is also a frequent contributor to the Governing podcast, The Future in Context. Clay’s most recent book, The Language of Cottonwoods: Essays on the Future of North Dakota, is available through Amazon, Barnes and Noble and your local independent book seller. Clay welcomes your comments and critiques of his essays and interviews. You can reach him directly by writing cjenkinson@governing.com or tweeting @ClayJenkinson.