Johns Hopkins Hospital anchors an expanding network of medical facilities on Baltimore’s east side. To the north, the Johns Hopkins University campus covers some 140 acres. Nearby, the grounds of Loyola University Maryland stretch out over 80 acres. In all directions of the city, a large roster of governments, universities and nonprofits own parcels of land. Yet the one place where most of these plots are noticeably absent is on the city’s property tax rolls.

In all, the value of property owned by governments, nonprofits and other tax-exempt organizations totals $15.1 billion -- 30 percent of Baltimore’s entire assessed value. Six years ago, exempt properties accounted for only 25 percent of the total value. But since Baltimore relies on property taxes for half its revenue, the increase is a significant hit to the city’s pocketbook. In 2007, Baltimore’s tax bill for all exempt properties would have totaled $202.4 million if they were taxable at the current rate. This year, the city would have collected $343.2 million. “It’s a long-term issue that we can’t ignore,” says Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. “Doing nothing isn’t an option.”

Baltimore is hardly alone. A pattern of property disappearing from tax rolls has developed across many of the nation’s urban cores as cities grapple with dwindling tax bases. In 16 of the 20 most populous cities with available data, tax-exempt properties today account for a higher share of the total assessed value then they did five years ago, according to a Governing analysis of assessment rolls. Nearly 29 percent of Jacksonville, Fla., property, for instance, was not taxable in 2011, up from 21 percent of the assessed value in 2006. Similarly, the assessed value of exempt Phoenix properties swelled from $2.5 billion in fiscal year 2007 to $3.8 billion in fiscal 2012, even as the city’s total taxable assessed value remained about the same.

The tax base is under siege from many quarters. In most cities, it has deteriorated with the recession and the bursting of the housing bubble. The degree to which newly exempt property has cut into revenues or caused tax rate hikes varies greatly across the country, with some cities far more reliant on property taxes than others. The bulk of exempt property in Baltimore and most other large cities belongs to governments. Accordingly, local governments buying up vacant parcels for redevelopment or states acquiring additional land are contributing factors to more property coming off tax rolls.

Part of some cities’ jump in exempt property can also be traced to hospitals, universities and other nonprofits occupying valuable real estate. Baltimore’s total property exemptions for religious and nonprofit institutions climbed approximately 76 percent from fiscal year 2006 to 2012, while taxable values increased 35 percent. Nationwide, the number of nonprofits grew by 25 percent between 2001 and 2011. It isn’t just the sheer number of them that’s impressive. It’s that these nonprofits are also economic engines for cities. The National Center for Charitable Statistics at the Urban Institute reports the nonprofit sector is expanding faster both in terms of employees and wages than business and government, and the industry’s share of GDP rose from 4.86 percent in 2000 to 5.4 percent in 2010.

As the problem compounds, state and local governments have embarked on a serious search for answers. Their approaches range from stepped-up efforts to collect voluntary payments in lieu of taxes (PILOTs) to targeting the definition and basis for a nonprofit’s tax exemption. But a comprehensive solution to replenish municipal coffers and shift the tax burden away from residents has yet to emerge.

Property tax exemptions are most prevalent in capital cities and college towns, where the top employers -- governments and universities -- are also tax-exempt property owners.

Some cities in financial turmoil are home to particularly high numbers of exempt properties. In Harrisburg, Pa., the state capital whose bankruptcy filing was rejected last year, nearly half the total assessed property value is exempt. Much of that property belongs to the state. If Pennsylvania paid taxes on its holdings, its annual bill would total $4.1 million, according to the city. Pennsylvania does, however, appropriate money to cover fire protection costs. It contributed $496,000 last year and boosted the allocation for the current fiscal year to $2.5 million as part of the city’s fiscal recovery plan.

Other cities increasingly feel the same pain as more public entities and nonprofits cross property off tax rolls. Of the few localities Governing analyzed where the exempt share of total property value did not increase, only Fort Worth, Texas, showed a decline exceeding 1 percent.

Many cities respond by negotiating PILOT agreements with nonprofits, typically taking the form of long-term contracts. In a recent survey of jurisdictions throughout the country, the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy found at least 218 localities in 28 states initiating PILOTs since 2000. The survey also reported educational and medical institutions fund 90 percent of all PILOT revenue, with much of the total from hospitals and universities in the Northeast.

However, PILOT revenue hardly registers on most city budgets, generating only 0.13 percent of a typical locality’s general revenue, according to the study. “It just isn’t really a game changer for most municipalities,” says Adam Langley, a research analyst who co-authored the report. For instance, Boston’s PILOT program is the nation’s largest -- collecting $19.4 million from 34 educational, medical and cultural institutions last fiscal year. Still, the total only accounts for 1.5 percent of its property taxes.

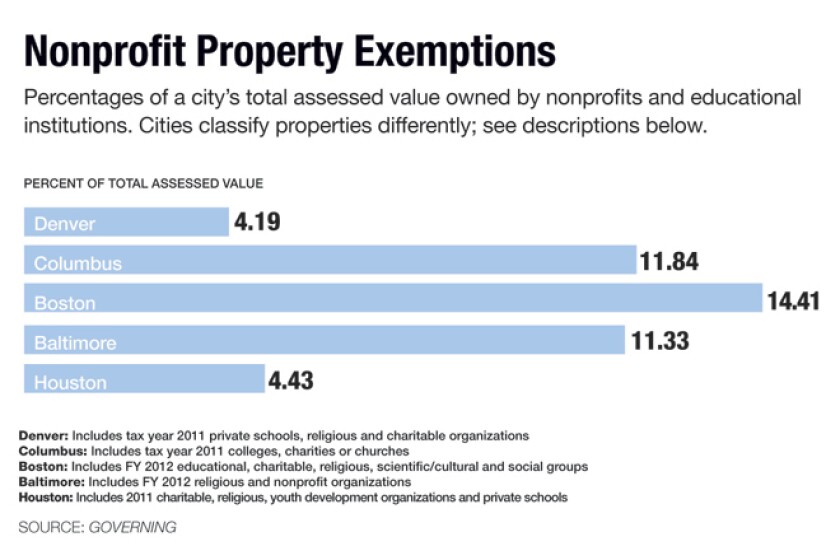

Baltimore’s experience is typical of the tricky balancing act cities face. In 2010, Baltimore formed a six-year PILOT agreement with state hospital and university associations totaling $20.4 million through fiscal year 2016. Rawlings-Blake acknowledges the PILOT is only a temporary revenue stream and one dwarfed by nonprofits’ property tax exemptions. But she notes that nonprofits, which own approximately 11 percent of the total property value, remain key to the city’s economy. “We have to figure out a way to balance the contributions these nonprofits are making,” she says, “while at the same time acknowledging the fact that there is a shared burden for the core services the city provides.”

The nonprofits felt pressure in 2010 after a bill introduced in the City Council proposed a bed tax for exempt institutions. Joseph L. Smith, director of local government affairs for Johns Hopkins Medicine and Johns Hopkins University, says the institutions already pay utility fees and provide numerous benefits to the community. “We don’t think it’s good public policy to have our real estate taxed,” he says. “Having said that, we recognized at the time the city had a budget deficit.” The hospital system and university contributed $5.4 million this fiscal year, an amount set to decline over the length of the agreement. It’s too early to know whether Hopkins will enter into another PILOT after 2016, but Smith says a decision likely hinges on the economy and the city’s financial situation.

In fashioning PILOTs, there is no cookie-cutter formula applicable to all cities, says G. Reynolds Clark, a vice chancellor at the University of Pittsburgh, who co-chairs the Pittsburgh Public Service Fund. In his talks with other nonprofits, Clark is careful to avoid using the terms “PILOT” and “taxes.” “There’s a concern that if you acknowledge making a payment in lieu of taxes, you’re admitting you should be paying taxes,” he says. It’s more important, Clark suggests, for city officials to initiate an open dialogue with nonprofits instead of simply demanding they pay up. “I believe a common denominator can be found that everyone can work with,” he says.

Woods Bowman, a DePaul University professor who has studied exemptions, says PILOTs are often unpredictable and not transparent. When a city is about to lose property from the tax rolls, he suggests it could assess a one-time impact fee. Such fees are on more solid ground legally, he says, and they would allow groups to count payments against project development costs.

A different type of deal was struck earlier this year when University of Pittsburgh Medical Center bought a parcel of land from a Pennsylvania township for a new hospital, agreeing to annually pay 50 percent of the assessed value in property taxes. The arrangement led some officials in the region to speculate about forging similar agreements with other exempt institutions.

Apart from PILOTs, more officials are questioning the definitions used to qualify nonprofits for tax-exempt status. Most state laws list a myriad of qualifying group types. There’s typically a catch-all term, such as “charity,” that’s open for varying interpretations, leading to court challenges, many of which reach state supreme courts. “People are identifying the issues and learning how to bring these challenges or at least talk about them,” says Evelyn Brody, a professor at the Chicago-Kent College of Law. Although variations in state laws are relevant, Brody says what’s happening on the ground in each area is more important.

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court raised eyebrows in April when it ruled a Brooklyn-based Orthodox Jewish summer camp did not qualify as a purely public charity. In the case, the court asserted supremacy of its 1985 decision establishing a five-point test granting charities tax-exempt status. At issue was one requirement to “relieve the government of some of its burden,” which the camp failed to satisfy.

Some jurisdictions are looking into modifying their definitions. But, Brody says, about half of states outline exemptions in their constitutions, meaning such changes would be difficult.

The exempt status of nonprofit health-care facilities, in particular, is receiving far greater scrutiny. Some states set mandates for amounts of free or discounted care tax-exempt hospitals must provide low-income patients. Texas nonprofit hospitals, for example, must devote at least 4 percent of net patient revenue to charity care. Illinois Gov. Pat Quinn provided clarity to state rules this summer when he signed a bill setting clear guidelines. A tax-exempt hospital can retain its exemption by providing charity care or health services equal to or exceeding its estimated property tax liability, which would be determined by a third party.

California Senate Majority Leader Ellen Corbett also called for tightening of rules for nonprofit hospitals in her state. The impetus was a state audit in August that found exempt hospitals were not required to provide specific amounts of uncompensated care or community benefits. At the four nonprofit hospitals auditors looked at, each one used a different method of calculating uncompensated expenses.

Nonprofit hospitals are fighting back, arguing that charity care is not the best or only measure of actual community benefit. Anne McLeod, the California Hospital Association’s senior vice president of health policy, says affluent communities demand different services than low-income areas where there is more of a need for charity care. “By painting broad brush strokes on everyone, you run the risk of putting unfair demands on some hospitals,” McLeod says. The association opposes narrowing the state’s exemption requirements, arguing they’re already shortchanged in Medicare and Medicaid payments. And in theory, once the Affordable Care Act is implemented, demand for charity care will be minimized since more people will be insured.

No one is suggesting churches or soup kitchens lose tax exemptions. Brody suspects that nonprofit hospitals are eyed because they compete with for-profit facilities. Moreover, the high salaries of hospital executives likely draw the ire of some officials. “You see these pressure points that make the states ask questions that they might not have asked before,” Brody says.

Most exempt nonprofits already pay sales tax and utility fees. It’s also important to note that many nonprofits own no property. An analysis by Joseph Cordes, a George Washington University economics professor, found only half of nonprofits reported owning real property on their 2009 IRS 990 forms. Some assessment offices don’t expend much resources reassigning values to the properties nonprofits own. The Cook County, Ill., Assessor’s Office and three others contacted for this story could not provide exempt property value totals.

In employment hubs, workers living outside city limits exacerbate property tax woes. As Michael Pagano, dean of the College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois at Chicago, points out, these workers converge on downtowns during the day, requiring public safety and transportation services, but typically don’t contribute property or income taxes.

In Baltimore, officials have responded with a balance of new taxes and credits. William Voorhees, director of revenue and tax analysis for the city’s finance department, says it wants to tax commuters who work there and don’t pay any local taxes. So far, this approach has been limited to taxes on parking and beverage containers. Meanwhile, the property tax rate remains one of the region’s highest, so the city implemented a homeowner’s tax credit this summer. Baltimore property owners subsidize an average of $1,575 in annual tax liability for exempt properties, including public buildings, before credits. Long term, Voorhees says, the city plans to diversify revenues and continue to push down property taxes.

Some local governments lean heavily on property taxes, particularly in the South, Northwest and New England. Property taxes accounted for 65 percent of Boston’s fiscal year 2012 revenue, compared to less than 10 percent for Columbus, Ohio.

Other localities have addressed revenue losses by attaching fees for water and other services. “Cities are being very intelligent in trying to figure out how to charge for the demand for services in a way that doesn’t violate the tax-exempt status of the property owner,” Pagano says. In Ohio and Kentucky, workers pay some income tax to their place of employment. But in other areas, the tax structure often doesn’t link the user of a service to its cost.

This has to change, Pagano says. “What we’re facing is one of those once-in-a-many generation opportunities to fundamentally revisit the social compact between a city and a region.”

View tax exempt property assessment data for U.S. cities