But in the following months, many of those laid-off teachers were recalled, thanks in part to a timely injection of stimulus funds. In all, the U.S. Department of Education reports the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) funded about 4,400 education jobs throughout the state in the 2009-2010 school year.

ARRA played a large role in propping up schools and some other public sector payrolls for a few years as state and local tax revenues plummeted and agencies sought to stave off job cuts. Where these positions stand today, though, varies greatly. Some governments eliminated ARRA-backed jobs when funding expired, while others managed to hold onto the positions.

The degree to which remaining positions funded by ARRA could soon be on the chopping block depends on a range of factors, from how agencies originally applied grant dollars to, of course, the degree of fiscal strain that municipalities or states are under.

To understand the extent to which ARRA upheld government payrolls, it’s important to first consider the goals of the program.

The administration viewed stimulus dollars as a stop-gap measure, not a long-term effort to sustain employment, said Edward DeSeve, former special adviser to the president for Recovery Act Implementation. And while the money helped plug holes in state and local budgets, DeSeve said the White House didn’t necessarily target money specifically for government employees.

Want more management & labor news? Click here.

ARRA funds did more to preserve existing public sector jobs vulnerable to cuts than create new slots, DeSeve said, mostly because of the poor fiscal health of recipient governments at the time.

“It was absolutely critical in being able to maintain employment levels, especially in education,” DeSeve said.

It’s unclear exactly how many government jobs ARRA ended up saving. Officials with the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board could not provide any estimates, and ARRA jobs data does not distinguish between public and private sector jobs.

But during the peak period in 2010, ARRA directly funded between 582,000 and 750,000 total jobs per quarter, according to Recovery.gov.

For the public sector, teaching positions accounted for the bulk of jobs ARRA sustained, largely by a massive, one-time allocation known as the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (SFSF) program. States collectively received $53.6 billion in SFSF funds, which they then distributed to localities using their own formulas. The federal government required states to route 81.8 percent of SFSF funds directly to schools; the remainder supported other areas of government, with much of the money going to public safety agencies.

The Department of Education tallied nearly 370,000 total ARRA-funded education jobs and 53,000 other positions during the 2009-2010 school year.

A survey conducted by the Center on Education Policy illustrates just how much ARRA bolstered the sector. About 69 percent of surveyed school districts reported stimulus funds saved or created jobs in 2010. Of those with funding declines, SFSF funds made up for a majority of the decrease in 52 percent of districts. But ARRA money still wasn’t enough to bridge funding shortfalls in many of these districts, with 85 percent of those still seeing overall funding declines that required cutting staff for the 2010-2011 school year.

Part of how payrolls fared post-ARRA is explained by strategies governments employed in utilizing their funds.

Some initially hoped ARRA funding would set a new baseline for federal education aid, but districts soon realized this wouldn’t be the case. "When it was clear this was a one-time infusion of funds, it shifted the conversation," said Noelle Ellerson, assistant director of policy analysis and advocacy for the American Association of School Administrators.

This conversation included making tough staffing decisions. On the one hand, accepting ARRA funds meant keeping student-to-faculty ratios down, at least temporarily. But by doing so, districts faced the prospect of layoffs once federal funds expired.

As a result, DeSeve said, some school districts were hesitant to accept funds.

Public safety agencies found themselves in a similar predicament.

Because law enforcement officers typically require several months of training after they’re brought on board, departments would reap little benefits from short-term help.

Managers interviewed for a 2010 GAO study examining the Recovery Act expressed concern of a potential “chill effect” of laying off workers hired with ARRA funds.

Officials in New York localities and North Carolina state government indicated they did not want to hire employees and later trim payrolls once federal funds were depleted. One Georgia service provider opted to instead hire contractors with stimulus funds, avoiding potential layoffs.

Whether agencies held onto ARRA positions can also be traced back, in part, to the strings attached with the various stimulus programs.

The COPS Hiring Recovery Program, for example, provided three years of entry-level salaries and benefits for 4,699 sworn officers stationed in more than 1,000 local police agencies. Upon completion of the three-year term, the grant required agencies to retain officer positions for an additional year or lose eligibility for future COPS grants.

The Justice Department awarded many of the COPS grants in late 2009, and those recipient agencies are now nearing the end of the additional fourth year.

Governing contacted a few agencies to check on the status of COPS grant-funded positions.

The Cleveland Police Department has retained 50 officer positions previously slated for layoffs that were averted with a grant. In California, the Los Angeles Police Department received a $16 million COPS award funding 50 positions. The agency said it was confident it could retain the jobs well into the future. Similarly, the Orlando (Fla.) Police Department reported it continues to employ its 15 COPS grant-funded officers.

But other localities, particularly school districts, already cut jobs when their ARRA funding expired.

The Philadelphia School District created approximately 1,900 new jobs with stimulus dollars, only to eliminate all the positions in 2012.

Joe D'Alessandro, the district’s chief grant development and compliance officer, said the district was limited in how it spent funds by the federal government’s mandate requiring money to be spent quickly.

The district made another round of painful cuts earlier this summer, when schools laid off 3,800 employees to help plug a $300 million budget shortfall.

“We wanted to adopt a budget with the resources we had, not what we wanted or needed,” D'Alessandro said.

Meanwhile, Chicago Public Schools recently laid off more than 2,100 teachers and support staff on top of 850 earlier cuts. Mayor Rahm Emanuel attributed the layoffs to an approximately $1 billion deficit, lower enrollment and ballooning pension expenses.

AASA’s Ellerson expressed concern that further cuts stemming from federal sequestration could trickle down to school districts, depending on whether states step up to fill the fiscal gaps.

While Arizona school districts haven’t incurred a sudden wave of layoffs, they’re reeling from gradual cuts that compounded over the past five years, said Andrew Morrill, the Arizona Education Association’s president. Education support professionals – coaches, maintenance workers, and others – were often first to receive pink slips when schools needed to trim budgets.

Between fiscal years 2008 and 2013, Arizona cut per pupil spending by 22 percent -- more than another other state, according to a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report.

ARRA did help to bridge state spending reductions temporarily. But Morrill fears further cuts to school payrolls could be on the horizon absent any additional funding from the state.

“They’ve got to make an increase in funding or we’re going to be vulnerable to cyclical recessions,” he said.

Education Employment

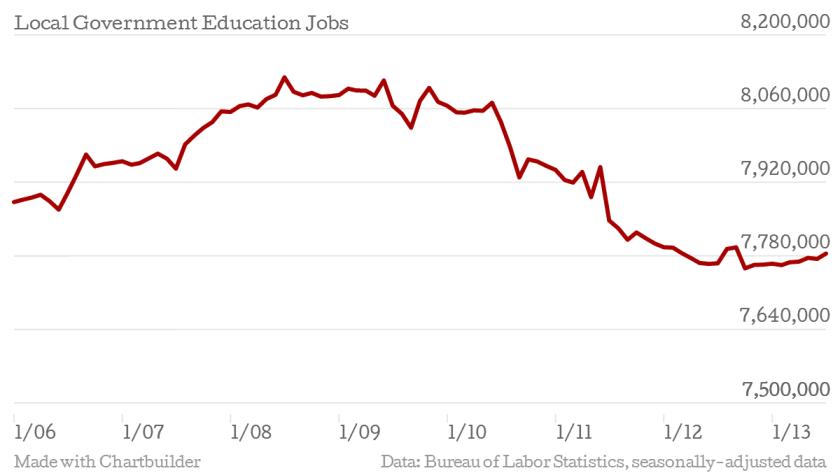

Teaching and related positions accounted for the majority of public sector jobs ARRA funded. Local education jobs fell sharply in the first few years of the recovery, as shown by the chart below. Last month, the Labor Department estimated localities employed about 7,780,000 education employees nationwide.