Thousands of protesters rallied outside the state capitol in frigid temperatures in February to express their anger before the state Senate voted. The Assembly held a heated all-night debate. But in the end, the Republican-dominated Wisconsin Legislature passed a right-to-work measure this session, making it the 25th state to enact such a law.

Wisconsin was this year’s poster child for labor-related warfare in state capitols. Gov. Scott Walker, who already had whacked collective bargaining rights for most public sector workers in 2011, has rocketed to the top tier of Republican presidential candidates largely because of his anti-labor efforts. His rise is a vivid illustration of how strongly Republicans feel about the issue.

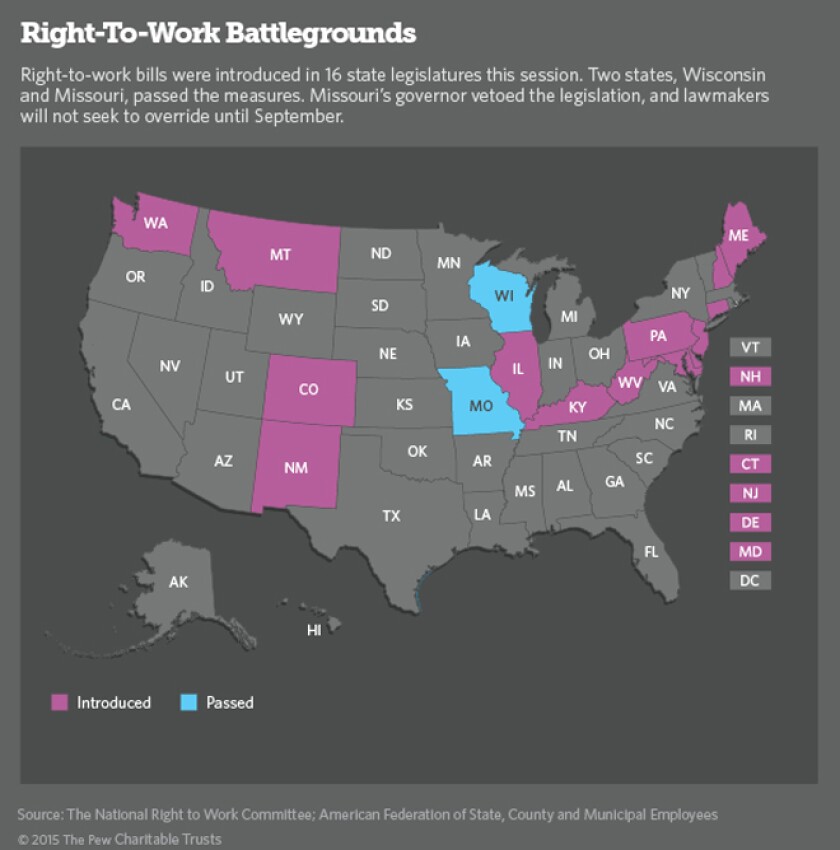

But Wisconsin was only one of about two dozen states where members of Republican-led majorities in one or both chambers introduced either right-to-work bills, aimed at preventing workers from being forced to pay union dues, or measures to roll back prevailing wage laws that establish workers’ pay on public projects.

In the end, right-to-work advocates scored some wins and suffered several defeats. Only two states — Wisconsin and Missouri — passed bills, although Democratic Gov. Jay Nixon vetoed Missouri’s. At least three states — Indiana, Nevada and West Virginia — repealed or scaled back prevailing wage laws.

The battles this year over the legislation — perceived as free-market initiatives by proponents and anti-union by foes — reflect the tremendous power that Republicans have gained in state capitols following November’s elections and the declining political clout of organized labor in many states.

“I think it’s part of a longer-run trend,” said David Macpherson, a labor economist who chairs the economics department at Trinity University in San Antonio. “Republicans have got more control of legislatures and governors than the Democrats do. That’s going to help these laws get passed. It’s the rise of Republicans and the decline of private unions.”

Thirty states have both legislative chambers controlled by Republicans. Twenty-three of them also have Republican governors.

“The growth and excitement we’ve seen on this issue is very positive,” said Patrick Semmens, a spokesman for the National Right to Work Committee. “Unions are a very powerful influence group. They spend a lot of money on politics and lobbying. We see Republicans more willing to take on the issue because they’re not worried about losing the political money support that unions often give to Democrats.”

Labor organizations that oppose such laws say that while a handful of states may have enacted some anti-union bills this session, many rejected them. And, they say, a growing number of Republicans are turning against legislation that would hurt union members.

In Missouri, for example, nearly two-dozen Republicans voted against a right-to-work measure that ultimately passed the legislature. In New Hampshire, 29 Republicans voted against a right-to-work bill that passed the House by a three-vote margin but was defeated in the Senate in a 12-12 deadlock (two Republicans voted no).

“I think there’s a growing awareness amongst many Republican legislators that passing right-to-work bills doesn’t help the struggling middle class. They do just the opposite,” said Brian Weeks, political director for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the largest public services employee union in the U.S. with 1.6 million active and retired members. “Attacking the institution of unions and working people is clearly not the answer to helping raise wages in this country.”

Right-to-Work Battles

Some of this legislative session’s most heated battles revolved around right-to-work laws, which prohibit workers from being compelled to pay union fees or dues as a condition of employment.The struggle over right-to-work has been politically polarizing and bitter. Both sides cite studies showing how such laws affect wages, job growth and state economies.

This session, right-to-work bills were introduced in 16 states, from Colorado to Maine. In some, the measures didn’t even get a hearing. In others, they were debated but couldn’t muster enough votes. In a few, they passed one chamber, but failed in the other.

In New Mexico, for example, a bill supported by Republican Gov. Susana Martinez passed the Republican-dominated House, but was blocked in a committee in the Senate, which is controlled by Democrats.

In Missouri, the Republican-controlled legislature passed a right-to-work measure, but it was vetoed by Nixon, who called it a threat to unionized workers and wages. Supporters will try to override the veto in September, but neither side thinks there will be enough votes.

A 17th state, Virginia, where both chambers have Republican majorities, already has a right-to-work statute. Legislators there went a step further, passing a resolution to add the language to the state constitution. It would need to be approved again by both chambers next session before it could appear on the November 2016 ballot.

Right-to-work proposals also cropped up in other states this year outside of legislatures.

In Ohio, a special commission of legislators and citizens that is reviewing the state’s constitution was asked to consider a proposal that would add right-to-work language. A committee and then the full commission would have to approve an amendment to be forwarded to the legislature, which could then put it on the ballot.

In Oregon, a petition drive to put right-to-work on a ballot initiative was launched but later withdrawn.

And in Illinois, where the legislature is under Democratic control, new Gov. Bruce Rauner, a Republican, has been pushing local governments to adopt “empowerment zones,” in which voters could decide whether workers in their area should have to join a union or pay dues. In Kentucky, not a right-to-work state, some counties have passed such measures. The actions are being challenged in court.

Right-to-work supporters, including business groups such as the Chamber of Commerce, say it’s unfair to workers who don’t want to be part of a union to force them to subsidize it through fees and dues.

“It’s an issue of individual freedom and choice for workers,” said Semmens, of the national right-to-work group. “They know best whether paying union dues is in their interest or not. They should make that decision for themselves.”

Right-to-work boosters, such as the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), a free-market think tank that drafts model legislation, argue that states that have such laws attract more businesses — improving wages and boosting the economy.

“The more states that pass right-to-work, the more pressure on the surrounding states to enact it,” said Michael Hough, a Maryland Republican state senator and director of ALEC’s Center to Restore the Balance of Government. “I think you’re going to see more of these bills. This is a trend.”

Labor organizations and their supporters strongly oppose right-to-work laws, saying that nonunion members benefit equally from negotiations with employers and that cutting off their dues and fees would threaten their very existence.

“Right-to-work just allows the freeloaders not to pay for their share,” said Wisconsin Democratic state Rep. Frederick Kessler, a labor arbitrator and staunch right-to-work opponent.

The groups also say that workers in right-to-work states earn lower wages and have declining incomes, which in turn weakens the economy. “Stronger unions mean a stronger middle class with better pay and better benefits,” said AFSCME’s Weeks.

Union membership has been declining in the U.S. over the years. In 2014, 11 percent of wage and salary workers were union members, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 1983, the rate was 20 percent.

“Those who propose these laws are doing it more out of anti-union sentiment than out of their concern for the rights of workers to join or not in general,” said Gary N. Chaison, a professor of industrial relations at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, who believes that workers should be free to make their own decisions about whether to pay union fees. “The attitude is, let’s kick them while they’re down and let’s not let them bounce back now that they’ve fallen so much on their own.”

Wisconsin Fight

In Wisconsin, the road to right-to-work legislation was bitterly partisan. In the Assembly, all 62 Republicans voted for the bill and 35 Democrats voted against. In the Senate, all 14 Democrats voted no, as did one Republican — a former union member.Democratic state Rep. Chris Taylor, who strongly opposed the measure, said that what happened in her state emanated from a national anti-union agenda being pushed by groups such as ALEC.

“You have a very empowered far-right contingent that has captured the Republican Party in Wisconsin,” Taylor said. “They are on a mission to really gut unions and decimate their political power.

“But we have a wage crisis in our state. We have flat wages,” she added. “The last thing you do is make it harder for people to be part of unions.”

Wisconsin Republican state Rep. Chris Kapenga, who co-authored the right-to-work measure, disagrees, saying it’s not a matter of being pro- or anti-union, but of individual choice.

“Some people love their unions. Others don’t like how things are handled in their unions, how they deal with their employer,” Kapenga said. “This [law] allows them freedom to choose.”

Kapenga said the law makes good economic sense for Wisconsin, as it will attract businesses that, because of union issues, stay out of states that do not have right-to-work.

Those are the same arguments Republican state Rep. Eric Burlison used when he sponsored right-to-work legislation in the Missouri House.

“We are surrounded by states that do have this freedom for employees,” Burlison said. “We’ve watched businesses leave and when they do leave, it has lasting impact. It’s clear that the grass is clearly greener on the other side of the border.”

Prevailing Wage Changes

The other hotly contested labor issue was whether to repeal or restrict prevailing wage laws. These laws require that workers on certain types of publicly funded construction projects be paid the going rate in a given area. The rate-setting method varies by state. In some, the numbers are determined through an annual survey of both union and nonunion contractors.As of January, 32 states had prevailing wage laws, according to the U.S. Department of Labor.

Bills to repeal or scale back prevailing wages were introduced in more than a dozen states. Virginia, in addition to Indiana, Nevada and West Virginia, passed legislation. But Democratic Gov. Terry McAuliffe vetoed the Virginia bill, and the GOP-led Senate couldn’t muster enough votes to override. In Wisconsin, a repeal measure squeaked out of an Assembly committee but did not make it into a budget bill. A bill to pare back the prevailing wage may be taken up separately on the Assembly floor this week.

Supporters say these measures are a sensible way for states to save money.

“Prevailing wage dramatically increases the cost of public construction, whether schools or roads,” said ALEC’s Hough. “Obviously, unions have benefited from it, but it’s been at a great cost to taxpayers.”

Opponents say prevailing wage repeal is just a way to chip away at unions and assail workers’ rights.

In some states, legislators are getting pushback against repeal from contractors who have been paying prevailing wage and don’t want it to disappear.

“The building trades’ employers have highly trained workers — plumbers, ironworkers — who have been getting paid the prevailing wage,” said Wisconsin Democrat Kessler, a prevailing wage supporter. “Companies look at that and say, we don’t want to have somebody whose skills are lacking.”

West Virginia state Senate Minority Leader Jeff Kessler (no relation), a Democrat, said that when his state took up the prevailing wage issue this session, he received an inch-thick stack of letters from businesses urging legislators not to eliminate or change the law.

“They’re getting a skilled workforce, not unskilled laborers who can end up causing cost overruns,” Kessler said. “It was the first time I saw labor and business line up together.”

Rather than repealing the law, the West Virginia Legislature, with a Republican majority in both chambers, passed a compromise that was signed by Democratic Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin. It exempts any publicly funded construction job that is $500,000 or less from the prevailing wage. It also requires that a new methodology be created to calculate the prevailing wage formula.

Republican state Sen. Craig Blair, who sponsored the measure, said that the new legislation will save taxpayers money, create jobs and allow government to do more projects and employ more people.

“The prevailing wage law was unfair to taxpayers. It was an absolute racket,” Blair said. “Someone who works construction six months out of the year makes $40 an hour and benefits under prevailing wage. Someone doing the same job in the private sector makes $20 an hour and works 12 months out of the year. It’s a pretty good gig if you can get it.”

West Virginia is temporarily without a prevailing wage for work on big projects because Republicans didn’t agree with the way a new rate was calculated under the new methodology that the legislature required by July 1.

Blair said that if Republicans were to vote now, they’d go for a full repeal. But Kessler said eliminating the prevailing wage would hurt both workers and businesses.

“It provides employers an opportunity to make a profit and pay our skilled laborers a decent wage and build quality projects on time and on or under budget,” Kessler said.

Kessler, who is running for governor in 2016, said this year’s prevailing wage battle in West Virginia has been a “real wake-up call to the labor unions.”

“Labor has its ears pinned up, and the radar’s on and they’re watching,” he said. “They know there’s an absolute distinction between the policies of the two parties on labor issues. I think you’ll see things will be very different in 2016 when it’s time for the elections.”