But most of the state’s other counties haven’t been as lucky, sustaining slight retail job losses over the decade. A geographic divide is emerging in Indiana, as in most parts of the country, as the retail industry shifts more of its business online. The bulk of the growth is taking place in relatively few areas.

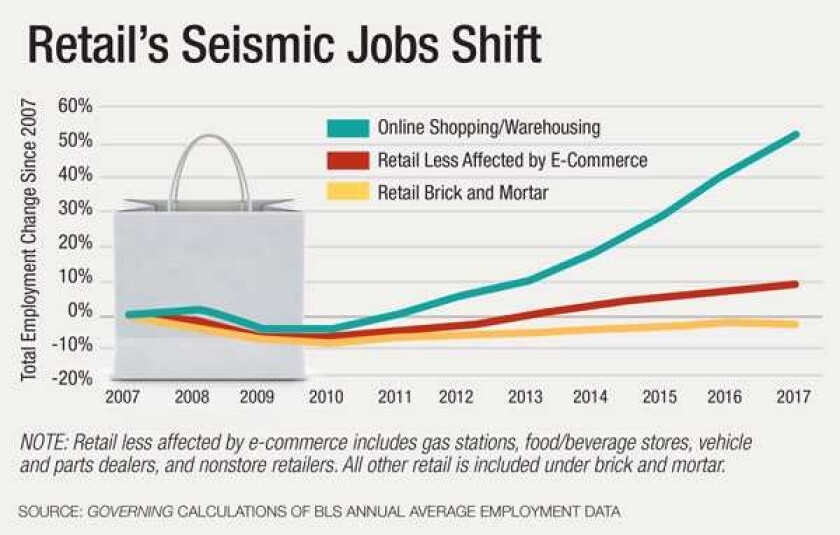

Contrary to what many believe, overall retail-sector employment continues to climb, albeit at a slower pace. But a look at Labor Department data shows different segments of the industry are headed in very different directions. While several types of brick-and-mortar establishments have stagnated, fulfillment facilities and call centers are rapidly proliferating.

To assess how the evolution of retail is playing out, we analyzed quarterly employment data for all U.S. counties over the 10-year period ending in the third quarter of last year. Jobs in two industries the Labor Department tracks that best reflect new e-commerce positions -- electronic shopping and warehousing/storage -- rose more than 50 percent. What’s really striking is how concentrated the growth was. Half of the 528,000 jobs created in these categories nationally occurred in just 31 of the nation’s more than 3,000 counties.

At the same time, traditional brick-and-mortar retail experienced a slight net job loss when excluding food stores, gas stations and auto dealers. In the past decade, nearly 60 percent of U.S. counties lost jobs in stores upended by online shopping.

While brick-and-mortar jobs can be found in every community, the same can’t be said of those tied to e-commerce. “Where the geography is lopsided, it’s a problem,” says Mark Cohen, director of retail studies at Columbia University Business School. “Someone who lives in a community and drives six or seven miles to a mall for employment is maybe not able to drive 30 miles to alternative employment in a distribution center.”

It’s an issue officials are already confronting in Plainfield. The Indianapolis bus transit system doesn’t extend to Plainfield, so officials there established two connector services for commuters that industrial property owners now fund via a self-assessed property tax.

The jurisdiction adding the most jobs in online shopping and warehousing over the decade was, not surprisingly, King County, Wash., where Amazon’s Seattle headquarters drove gains totaling 36,000. Other large urban areas, including Riverside and San Bernardino counties in California, also saw significant growth.

A lot of the other localities with large expansions, though, aren’t as recognizable. Kenosha County, Wis., and Lexington County, S.C., both of which landed large Amazon facilities, recorded the largest percentage employment increases. If there’s a common denominator in places where large fulfillment centers are opening, it’s that they’re strategically located near transportation hubs. Lexington County offers close proximity to three interstate highways and UPS air cargo shipping. And jobs at two Amazon facilities, while not high-paying, provide flexible hours for a large contingent of Lexington’s college students and military personnel.

Traditional retail is thriving in the nation’s fastest-growing large counties, many of them in Florida and Texas. Meanwhile, local economies tied to legacy industries and those incurring population losses continue to be vulnerable. DuPage County, Ill., and Orange County, Calif., both older suburban jurisdictions, sustained sizable employment declines in the traditional retail industries most affected by e-commerce. Each lost approximately 12,000 such jobs over the decade, behind only Los Angeles, the nation’s largest county.

While huge regional shopping centers are holding up well, Cohen of Columbia University foresees problems for smaller to mid-sized malls and their surrounding strip malls. “They are in increasingly deep trouble as their anchor tenants close and many of their specialty tenants that fill the concourses go bankrupt or consolidate their store fleet,” he says. “There were hundreds of malls that should not have been built.” Some developers have succeeded in reviving malls by adding gyms, restaurants or entertainment venues. But these are more the exception than the rule, as such renovations are expensive.

A Deloitte study found consumer behavior was more closely linked to income than to generational differences, with high-earners most likely to shop online. Discount stores and luxury retailers, which often don’t sell goods online, are still reporting strong revenue growth. It’s the “balanced” retailers in between that aren’t performing nearly as well. By our calculations, home furnishing stores (down 17 percent) and electronics and appliance stores (down 13 percent) incurred the steepest annual employment declines nationally over the last decade.

Rather than replacing jobs, the National Retail Federation’s Mark Mathews sees e-commerce as generating a shift in skill requirements. For sales associates, there’s a greater emphasis on troubleshooting customers’ concerns or assisting with online ordering, while online order fulfillment and longer store hours have supported additional positions. Mathews’ research indicates that the actual number of employees per store increased in recent years.

Retail store employees, who are disproportionately female, often don’t transition to fulfillment centers. LinkedIn examined the profiles of retail associates who took on new job titles in the past five years. The largest share of them became administrative employees or customer service specialists, with a sizable number also going back to school.

The explosion of e-commerce isn’t the retail industry’s first period of upheaval -- the introduction of the Sears catalog in the late 1800s and the shift from downtown retail to suburbs in the mid-20th century brought profound changes. There’s no way to be certain what the current move toward e-commerce and automation will mean for the workforce going forward. But industry observers expect the transition to occur more rapidly than prior shifts.

A recent report from the Investor Responsibility Research Center Institute estimates 7.5 million retail jobs are at high risk of computerization. Robots are already found in Amazon’s warehouses, and Lowe’s is piloting a robot that leads customers around and answers questions. “Retail may not look like it does today 20 years from now,” Mathews says. “But from our perspective, it will still be retail.”

Read Governing's full analysis.

View county-level retail and e-commerce data.