This and other factors have contributed to an alarmingly high number of residents taking their own lives. The area of approximately 8,000 people recorded a staggering 49 suicide deaths between 2012 and 2016 -- the highest rate of any county-level jurisdiction in the country.

Suicide is a perennial problem throughout the nation. The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data shows the 2016 national age-adjusted suicide rate reached the highest level seen in decades.

A review of the federal data, however, shows that it's rural America that is sustaining the largest increases. The aggregate suicide rate for counties outside of metropolitan areas climbed about 14 percent over the five-year period ending in 2016. By comparison, the rate within metro areas also increased -- but only by 8 percent. The largest metro areas, in particular, experienced relatively small increases compared to everywhere else.

The suicide rate is highest in the Western U.S., with Montana (26 deaths per 100,000), Alaska (25.4 deaths per 100,000) and Wyoming (25.2 deaths per 100,000) recording the highest rates. Rates were about three times lower in the more urban states of Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York.

Regional differences are largely a function of demographics.

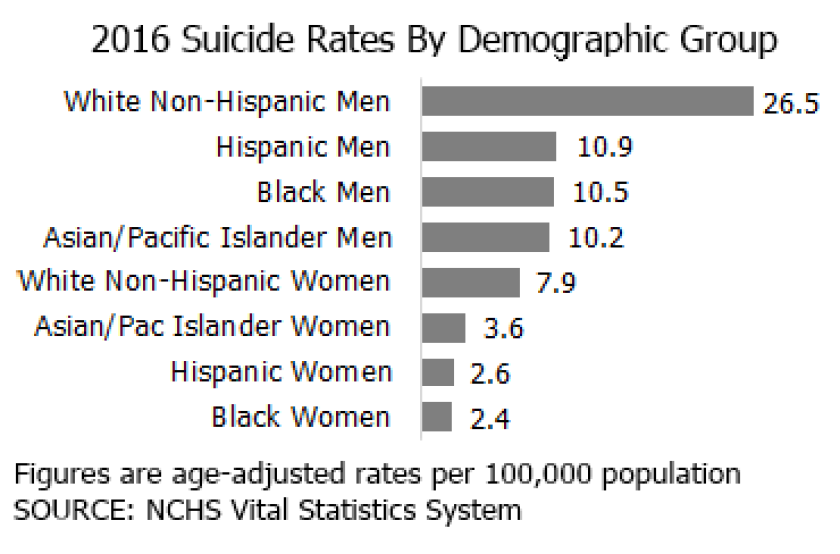

White men die at the highest rates -- roughly 10 times that of Hispanic women and black women -- because they tend to have greater access to firearms. Women, on the other hand, carry out more suicide attempts but generally do so using less lethal means.

Gun ownership, which is more prevalent in rural areas, also explains why certain regions have higher suicide rates. Firearms account for about half of all suicide deaths. Research has found that mandating waiting periods, gun locks and other gun control laws are associated with fewer deaths.

Alaska's Statewide Suicide Prevention Council recently published a five-year plan outlining problem areas and strategies. Like other rural parts of the country, many of the state's communities are without access to mental health care. Cultural attitudes can pose challenges, too: The stigma associated with mental health may dissuade individuals from seeking care.

Among Alaska's indigenous villages, Eric Morrison of the council says a loss of culture or language, as well as the trauma associated with decades of colonization, may also be affecting older natives and their descendants. “The web of causality differs from place to place,” he says. “If there was one simple answer, we would have solved this years ago.”

The fact that suicides occur more frequently in rural areas isn’t new. Recent CDC data, though, shows the disparity between rural and urban areas has slowly widened in recent years.

Reasons Behind Rising Suicide Rates

What’s actually driving up overall suicide rates isn’t fully understood. But there’s general consensus that it's a range of things. One often-cited factor is the economy.For a few years, some assumed that higher suicides were largely a consequence of the Great Recession. But even after several years of economic growth, mounting death tolls haven’t subsided. The national rate has now increased for 11 consecutive years.

Still, not all parts of the country have experienced the same economic growth, and it’s many of these struggling regions that are experiencing larger losses to suicide.

Princeton University professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton have conducted extensive research around what they call “deaths by despair” -- suicides, drug overdoses and alcohol-related fatalities. They found mortality among non-Hispanic whites to be rising for those without college degrees, and improving for more educated whites, blacks and Hispanics. The cumulative effects of few labor market opportunities and weakening social structures have largely contributed to worsening mortality for less-educated whites, although the authors note that economics alone don’t fully explain increasing suicide rates.

“It’s not the economics itself but the associated stress that leads to physical or mental effects on health,” says Jill Harkavy-Friedman of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The unemployed may lose health insurance or be unable to pay for treatment. More Americans are also likely, Harkavy-Friedman adds, to be living with chronic pain or other conditions today that influence mood or behavior.

Studies have singled out other issues compounding the problem. Marriage rates, for instance, have declined, and unmarried middle-aged men have been shown to be at particularly high risks of suicide.

Alternatively, part of the longer-term increase may simply have to do with how suicides are reported. Advocates say state reporting has improved, and suicide deaths are now better counted in state and federal data.

Seeking Solutions

West Virginia’s suicide rate -- historically one of the nation’s highest -- has continued its slow upward ascent in recent years. About two-thirds of the state’s fatalities involve firearms, so Barri Faucett, director of Prevent Suicide West Virginia, says her group is working to distribute gun locks and promote the idea that those suffering from mental health problems shouldn’t have immediate access to firearms. “We’re not telling people to get rid of their guns,” she says. “We’re just wanting to ensure that they’re kept safe during a critical time.”Alaska's five-year plan seeks to prevent suicides through several layers: promoting wellness to lessen suicide risks, improving awareness and understanding of suicide, and strengthening the services and supports provided to a person who is experiencing a mental or emotional crisis.

In Wyoming, Gov. Matt Mead hosts an annual symposium on suicide prevention.

And the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention is pushing an approach known as “Zero Suicide” that aims to improve care and outcomes for individuals at risk of suicide in health-care systems. The group is also focusing its efforts on emergency rooms and correctional facilities, two other places where people are at higher risk. The vast majority of suicide victims, in fact, suffer from a diagnosable mental health issue.

“By increasing public awareness of risk factors and warning signs, we can do something to stave off some of the deaths,” says Harkavy-Friedman of the foundation.

Suicide Rates by County

An interactive map shows 2012-2016 annual average age-adjusted suicide rates for all counties with reported data.suicidesbycountymap.png