But new research shows that if more seniors take advantage of that benefit, the federal and state governments could cut their health-care costs because seniors who receive food stamps are less likely to end up in a nursing home or hospital, and if they do get admitted, their stays are shorter.

A four-year study examined a group of seniors 65 and older enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid in Maryland. Benefits Data Trust, a nonprofit that works with social services agencies in seven states, conducted the study in partnership with state agencies and researchers from the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing and the Hilltop Institute at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

In the study's population, nearly everyone qualified for food stamps, officially known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), but only 47 percent participated. Giving food stamps to those eligible-but-not-enrolled seniors would translate to $2,120 in annual medical cost savings per SNAP participant, according to the report.

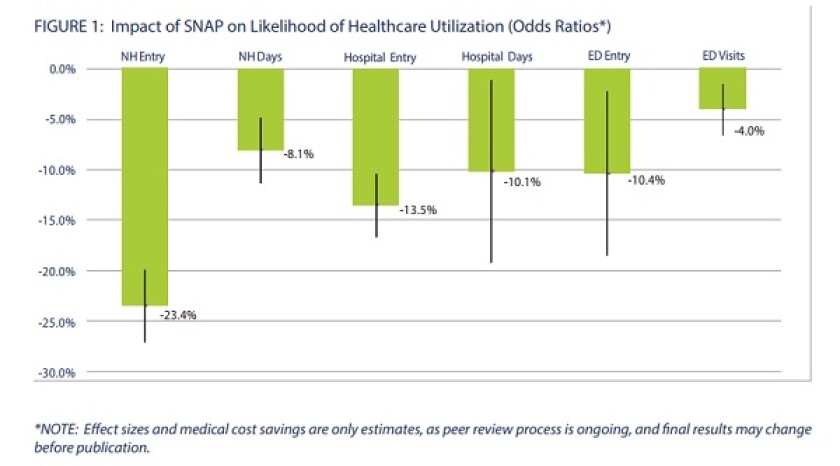

Receiving SNAP reduced the odds of being admitted to a hospital by 13.5 percent, an emergency department by 10.4 percent or a nursing home by 23.4 percent, and reduced the likely length of stay in all three settings.

Benefits Data Trust helps people enroll in public assistance programs, but the organization didn't have information on whether people's lives improved because they were enrolled in a program.

"We wanted to make sure that we weren't just increasing the rolls to increase the rolls," says DeAnna Minus-Vincent, the chief engagement officer at Benefits Data Trust.

Source: Benefits Data Trust

"It corroborates much of what we've known about the relationship between SNAP and well-being, particularly for older people," says Ellen Vollinger, a legal director at the Food Research and Action Center.

Past research collected by her organization shows food insecurity -- a lack of access to affordable and nutritious food -- among seniors is linked with a variety of health problems, including diabetes, anemia and depression.

The research findings illustrate the interdependence of public assistance programs, says Marlo Nash, a senior vice president at the Alliance for Strong Families and Communities. Poverty, unstable housing and hunger are all conditions that affect a person's health, even if they are not directly treated in a hospital or nursing home. Improving those so-called "social determinants of health" can make people healthier and less dependent on medical care.

Typically, government agencies running programs like SNAP or housing vouchers don't try to estimate the potential cost savings for the health-care system. That's a mistake, Nash says.

"There is a siloed approach to how programs are funded," he says. "This paper pulls that out."

Benefits Data Trust also wants the enrollment process for government programs to be more interconnected. When seniors enroll in Medicare and Medicaid, for example, they want seniors to be enrolled in SNAP at the same time.

Some states are already taking steps toward that goal. More than a dozen states have simplified the process for enrolling seniors in SNAP if they already receive Social Security Insurance. In the 1990s, South Carolina, the first state to participate in a so-called "Combined Application Project," increased SNAP participation among Social Security recipients from 38 percent to 50 percent in four years.

Putting more seniors on food stamps isn't the only way to keep them out of nursing homes and hospitals. That same goal can be achieved by increasing the average monthly SNAP benefit by $10, reports Benefits Data Trust. Doing so would reduce seniors' odds of entering a nursing home by 7 percent or hospital by 2 percent.

In March, North Carolina Congresswoman Alma Adams, a Democrat, proposed raising the minimum monthly allotment of SNAP benefits from $16 to $25 across the country -- but the bill lacks Republican support and isn't likely to pass this year.

Some communities, however, aren't waiting for congressional action. Last year, the District of Columbia used local funding to raise its minimum monthly SNAP amount from $16 to $30 per household.

An extra $10 or $15 per month might not sound like a lot, says Vollinger, but it would make a big difference for a low-income senior on SNAP. The annual income among people in the Benefits Data Trust study was $5,864. While the U.S. Department of Agriculture spent more than $70 billion on the SNAP program last year, that money went to feeding roughly 44 million households each month.

"Often the public is startled by how severe folks' circumstances are," Vollinger says. "They hear about SNAP as a very large program -- and it certainly is -- but it's serving a lot of people."

*Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Congresswoman Alma Adams represented Alabama. She represents North Carolina.