This practice is called psychiatric boarding, and it happens all over the country. It’s often the only option for emergency room staff; they can’t turn away mentally ill patients, even though they’re not trained to deal with them. Essentially, all they can do is stabilize the patients and keep them in bed, often in seclusion or strapped down for days or weeks at a time.

Psychiatric boarding is an ugly reality that patients and physicians reluctantly accept. But that wasn’t the case with the 10 patients in Pierce County. Their families sued the state.

Last year, the Pierce County case made its way up to the Washington state Supreme Court, where the justices ruled unanimously that psychiatric boarding was unlawful. Washington is still the only state with a law banning the practice, but in the wake of the court decision a surprisingly diverse coalition of physicians, mental health advocates and government health-care officials have begun calling for solutions to boarding. They say the practice is unethical and warrants a nationwide effort to provide more humane and medically effective alternatives to long, unnecessary ER stays. “Evidence all around us demonstrates the mental health care system is in crisis,” said Dr. LaMarr Edgerson, director-at-large of the American Mental Health Counselors Association, at a U.S. House committee hearing last year. The broken system, Edgerson explained, “is generating increased demand for inpatient psychiatric beds while simultaneously decreasing their supply.”

What the Pierce County patients experienced is the rule, not the exception. In a survey last year, the American College of Emergency Physicians found that 84 percent of emergency rooms said they board psychiatric patients, and it’s getting worse. More than 50 percent said they spend increasing time and energy trying to transfer those patients to appropriate psychiatric facilities.

In Washington state, emergency room physicians joined an amicus brief in support of the Pierce County patients, agreeing that psychiatric boarding resembled warehousing more than it did medical care. They painted a picture of hurried, chaotic emergency rooms that were adding to the patients’ agitation and anxiety. The physicians laid blame on the Washington Legislature, which cut mental health funding by more than $90 million between 2009 and 2012.

Physicians don’t want psychiatric patients waiting for weeks in the emergency room, and they’re searching for other options, says Stephen Anderson, who lives in Pierce County and sits on the board of directors of the American College of Emergency Physicians. So far, no court outside Washington state has weighed in on the issue, but emergency room physicians in half a dozen states have invited Anderson to talk to them about the Pierce County case. “Everybody is looking at it and saying, ‘Do we need to get to this point?’” Anderson says. “I don’t know a colleague anywhere in the nation who doesn’t have psychiatric boarding in their ER.”

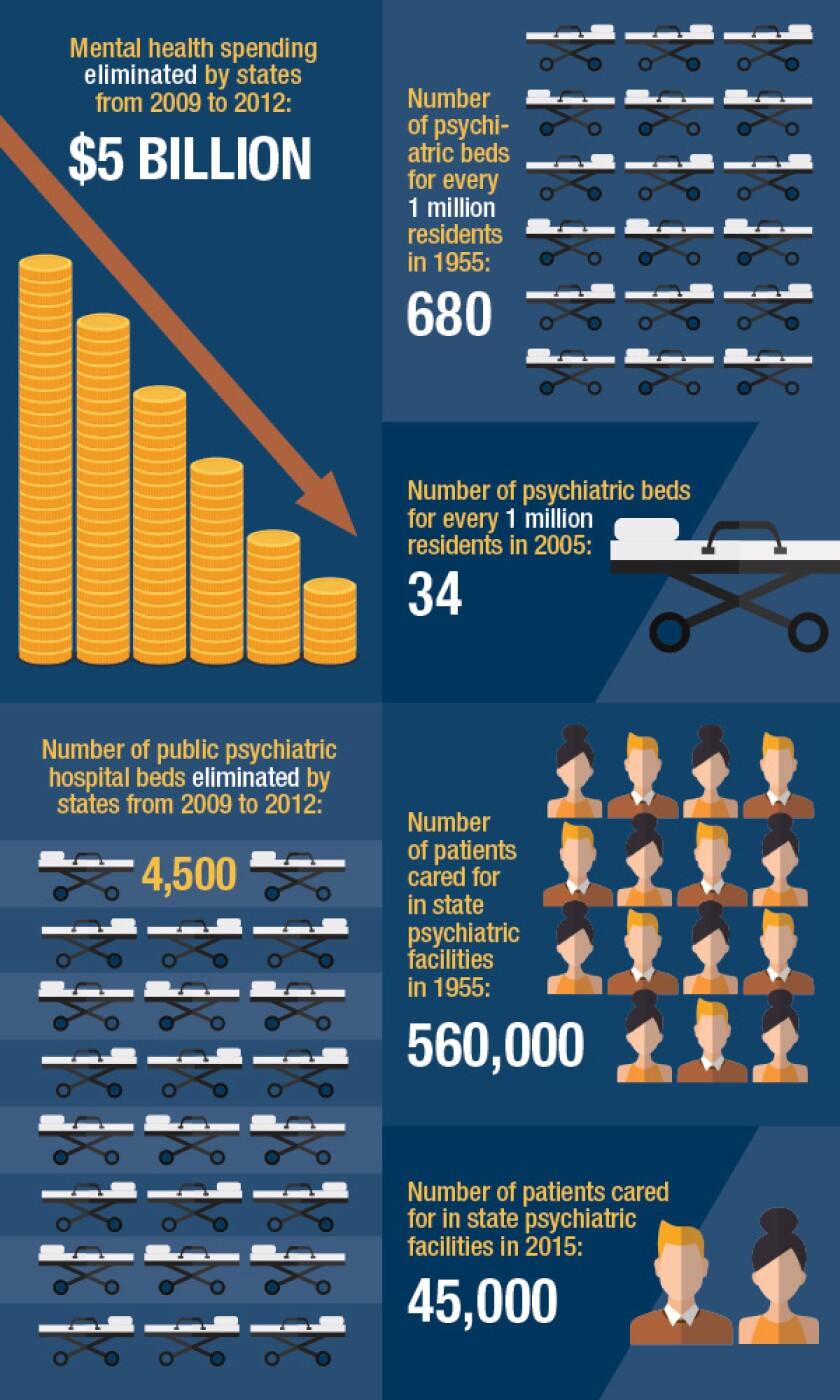

The fundamental reason boarding occurs is that there are more people with severe mental illness than there are psychiatric beds to house them. The gap is widening. Over a period of 50 years, starting in the mid-1950s, the per capita number of such beds in the United States decreased by 95 percent, from 680 beds per million residents in 1955 to 34 per million in 2005. Much of that decline is due to the closing of state asylums. In 1955, state psychiatric facilities cared for 560,000 patients. Today, they care for 45,000.

[click_to_tweet]The number of psychiatric beds in America has declined 95% since the mid-1950s.[/click_to_tweet]

The bed shortage is also the result of a provision in the 1965 federal Medicaid law that allows Medicaid reimbursements for psychiatric care only in small facilities. Up until that law took effect, states bore the responsibility of paying for psychiatric care, usually offered at large public mental hospitals. But those hospitals had earned a negative reputation as poorly maintained warehouses that made patients worse. So the law excluded psychiatric hospitals with more than 16 beds. The expectation was that smaller community-based facilities would take over much of the job of mental health treatment, and that these would be able to tap into Medicaid funding.

The exclusion of funds for large mental institutions was a political victory for a bipartisan coalition of fiscal conservatives who wanted to cut mental health spending and liberals who saw state hospitals as sites of human rights abuses. But the exclusion had an unintended consequence. For the first time, states could collect partial reimbursements from the federal government for psychiatric care as long as they shifted treatment away from the old public mental hospitals. What followed was the natural consequence of that financial incentive: a national movement not just to de-emphasize large state psychiatric hospitals but to close them altogether, a process better known today as deinstitutionalization.

The theory was that fewer patients would need the state hospitals because of advances in psychotropic drugs that could stabilize their conditions; any care they still required could be met by the smaller outpatient clinics and other community-based facilities. But very few of these smaller facilities were actually created. When states closed the older hospitals, they simply cut back mental health funding rather than switching to the new model. The minimum ratio of psychiatric beds to patients should be about 50 beds per 100,000 residents, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit dedicated to helping patients with severe mental illness. No state meets that standard.

Today, because there aren’t enough beds, a majority of the nation’s mentally ill end up homeless, incarcerated or as chronic visitors to emergency rooms. An estimated 16 percent of the prisoners in jails and state prisons have a serious mental illness. Anyone who has such an illness is about three times more likely to be in a jail or in a state prison than in a psychiatric facility. That’s why the Treatment Advocacy Center calls deinstitutionalization “the greatest social disaster of the 20th century.”

Federal health officials have been trying to undo some of the damage that the defunding of large mental hospitals has caused. In fact, a section of the Affordable Care Act calls for research to see what would happen if Medicaid went back to reimbursing these institutions for treating patients. In 2012, 11 states and the District of Columbia agreed to participate in a demonstration project to test whether a change in the Medicaid payment model would result in better access to psychiatric care while also lowering Medicaid costs. If the demonstration worked as proposed, mentally ill patients would spend less time in emergency rooms and psychiatric boarding might begin to fade away.

Both state Medicaid officials and their federal counterparts have reason to believe the experiment will be a success. In Maryland, for example, the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reported that the daily cost of care for a mental patient at an acute care hospital is $2,965. At a private psychiatric facility, the cost is $864. “Not only do we know that it is cost-effective, but we know that this is what they do: It’s their specialty,” says Shannon McMahon, Maryland’s deputy secretary of health-care financing. While a general hospital might have staff with behavioral health expertise, she says, “you want to go to the place that does it the most -- a center of excellence.”

Up until now, in many states, these centers of excellence have primarily been available to people with private health insurance through their employer. Thus, the demonstration is also testing what would happen if low-income patients covered by public health insurance had better access to private facilities that specialize in psychiatric care. Would their health outcomes be better? Would they spend less time in emergency rooms? Medicaid patients have a right to find out, says Andrew Sperling, director of federal affairs for the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “We ought not to say that just because you’re on Medicaid and poor, you can’t go to those places.”

The demonstration finished last summer, but a third-party evaluation by Mathematica Policy Research, a private contractor, won’t be completed until September of next year. That didn’t stop U.S. Sen. Ben Cardin of Maryland from ushering a bill through the Senate that would extend the project for an additional year and expand it to large public psychiatric facilities in the 11 states, so long as it didn’t increase net spending in the overall Medicaid program. (The Congressional Budget Office scored the bill as costing $100,000 in direct spending over the next 10 years.) As of November, a companion bill in the House was in committee but hadn’t received a hearing.

A parallel effort with similar goals is also garnering attention. Earlier this year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released a proposed rule that would affect more private hospitals and could open access to more beds. The rule would grant a waiver for large private psychiatric facilities to receive Medicaid managed care payments for short-term stays of less than 15 days. Unlike the demonstration, it would apply nationwide.

But the demonstration project and the federal waiver in no way constitute a solution to the problem. Under the demonstration, Medicaid reimbursements are available to only a subset of patients with serious mental illness: adults between the ages of 21 and 65 who have expressed suicidal or homicidal thoughts or gestures, or patients deemed dangerous to themselves or others. In its interim report, Mathematica notes that children under 21, adults older than 65 and patients with many common mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia, don’t qualify.

The same interim report notes that the average length of stay for a patient was 8.2 days. At first blush, that seems like good news, since it suggests that making Medicaid payments available for 15-day stays would cover the average patient. But the demonstration only looked at a narrow subset of potential patients. Other data suggest the median length of stay for all psychiatric patients well exceeds 30 days. Even with high-quality specialty care, many aren’t ready to return to the community in two weeks.

And even if the federal government unlocked Medicaid as an insurer for private psychiatric care, the overall system would still have far too few beds to meet demand. The Treatment Advocacy Center estimates that to reach a minimum level of psychiatric care, as many as 95,000 new beds would be necessary.

Given all these problems, some health-care advocates have proposed a remedy that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago: returning to the traditional mental hospital, the very institution that reformers fought so hard to abolish in the 1960s. Last January, Dominic Sisti and two co-authors from the University of Pennsylvania medical school called for the return of long-term psychiatric care in a journal article titled, “Bring Back the Asylum.” They wrote that “for persons with severe and treatment-resistant psychotic disorders, who are too unstable or unsafe for community-based treatment, the choice is between the prison-homelessness-acute hospitalization-prison cycle or long-term psychiatric institutionalization.” They left no doubt that they considered institutionalization to be the best option.

Shortly after the article ran, Sisti says, “I was deluged with cranky and almost angry emails.” Some critics accused him of advocating a return to the inhumane treatments and overcrowded conditions portrayed in Ken Kesey’s famous book, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Sisti and his co-authors responded that they were asking readers to imagine a new type of institution, one that would be a safe and caring refuge for mentally ill patients who were unsuited for community-based care. They wouldn’t be the asylums of the 1950s and wouldn’t have to be called asylums, despite the perhaps unfortunate title of the article. “We have this hole in our spectrum of health care for mentally ill individuals,” Sisti says. “We were looking to inject ourselves into the conversation.”

The Washington state Supreme Court ruled last year that psychiatric boarding is unlawful. (Flickr/Harvey Barrison)

Last year, when the Washington Supreme Court ruled that psychiatric boarding was unlawful, it didn’t spell out a remedy. In practice, that meant people could still end up in the emergency room during a psychotic episode. The court directed that hospitals have a psychiatrist available to screen the patients and then return every day to make evaluations and prescribe medication. “It was not an unreasonable thing to have asked for,” says Anderson, the emergency room physician in Pierce County. But smaller general hospitals don’t have the personnel to comply with the decision. As Anderson puts it, “you had to turn them loose after 72 hours, or you had to hope that nobody was going to arrest you.”

The court put a four-month stay on its ruling, giving Gov. Jay Inslee and the legislature time to make changes that would relieve some of the pressure on emergency rooms. He found $30 million for new mental health funding, and he prevented the elimination of almost 40 state psychiatric beds across the state. Inslee also converted 140 psychiatric beds previously set aside for voluntary-commitment patients and repurposed them for patients committed involuntarily.

In addition, the legislature passed a law this year that allows emergency rooms to use telepsychiatry to conduct an initial patient evaluation. Staff bring a screen to the patient’s bed and a psychiatrist consults remotely. Because the consultation is taking place in an emergency room, not a large psychiatric facility, Medicaid pays for it.

Telemedicine is a modest fix for some of the smaller general hospitals in rural and small-town Washington, where too few psychiatrists are available to work in emergency rooms. With telemedicine, a psychiatrist anywhere in the country can reach an initial diagnosis, prescribe medication and help the emergency room physicians decide whether the patient requires long-term psychiatric care somewhere else, or can return to the community in a few days.

But the mental health system in Washington doesn’t just need psychiatrists, it needs beds, and they will remain hard to come by for the foreseeable future, despite the court decision and its aftermath. “The state moved it from the back burner to the front burner and it has helped us,” Anderson says. “It’s a whole lot further than we were two years ago, but the need for inpatient psychiatric care is not going away.”