As he seeks a third term this fall, Walker isn’t talking about any of that.

Touring meeting halls and dairy farms across the state, he touts his record cutting income and property taxes to the tune of roughly $8 billion. He insists he’ll keep felons sitting in jail longer than would his Democratic opponent, Tony Evers, the state superintendent of public instruction. Other than that, however, Walker often seems like he’s taking notes from the Democratic playbook, keeping his focus on education and health care. “Sometimes, I’ll hear from our capital press corps, those are Democrat issues,” Walker tells me between campaign stops. “That’s baloney. They’re issues that people care about.”

Despite his protests, it’s clear that Walker is trying to appeal to voters in the center. It’s a striking strategy for someone who has spent much of the past decade as a polarizing conservative ideologue. It also runs counter to this year’s trend of candidates from both parties doing all they can to rally their bases, counting on allegiance to President Trump, or revulsion to him, to be more of a motivating factor than any state-level issues. “He really is running as Mr. Moderate,” says Mordecai Lee, a former state legislator and a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “It’s not go big and go bold. It’s been go small and go moderate.”

Walker describes his most recent education budget as the largest investment in schools in Wisconsin history (although it came after deep cuts during his first term). The budget included the state’s first sales tax holiday for back-to-school shopping, as well as a tax credit for any parent with a child under 18. In August, he unveiled a plan to give college students who remain in the state after graduation a $1,000 tax credit per year, for up to five years. Democrats dismiss those items as “candy” meant to make it easier to swallow budget cuts elsewhere, but the not-so-accidental political timing means that parents across the state will be receiving $100 checks just as the election is approaching.

Walker unfailingly notes that while unemployment in the state topped 9 percent back when he first ran in 2010, it’s been under 3 percent for much of this year. College tuition doubled in the decade before he took office, but it’s been frozen now for six years straight. He inherited a budget shortfall of $3.6 billion, but the state is now running surpluses, despite all the tax cuts. Walker certainly benefits from the political equivalent of “buying low,” taking office in the teeth of the worst recession in generations, but there’s no question that, economically at least, the state is in better shape now than when he was first elected. “We have a habit of picking people who have a track record people can judge them on,” says Wisconsin Assembly Speaker Robin Vos. “If that’s the case, I don’t see how Gov. Walker doesn’t win reelection in a landslide, frankly.”

But Vos knows that, while Walker has a solid floor of support, he also bumps up against a constricting ceiling. Polls over the past couple of years have shown, on average, that roughly 48 percent of the voters in Wisconsin approve of the governor’s performance, while about 48 percent disapprove, most of them strongly. There aren’t many people who are neutral. The day before the August primary, Walker himself said Democrats could put Daffy Duck on the ballot and get 48 percent of the vote for governor. Walker has won three times -- two of them in the Republican wave years of 2010 and 2014, and the other in the recall election of 2012, launched in response to his union busting measure, known as Act 10. But each time, he’s taken only 52 or 53 percent of the vote. “He still has close to half the population who hates him with a passion,” says Mike McCabe, who ran unsuccessfully for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination.

Walker has not faced an electorate as hostile to his party as the one this year, and he knows it. In January, when Democrats flipped a state Senate district that had voted strongly for Trump, Walker took to Twitter to warn conservatives that the result should serve as a wake-up call. Democrats flipped another district in June, after winning an expensive and contentious state Supreme Court race in April. “In 2010 and 2014, nationally the wind was at our back,” Walker says. “In this election, the national wave is coming at us.”

A tougher political environment could be enough to bring his share of the vote down below 50 percent. Certainly both parties see this as a marquee election, with the Republican and Democratic governors associations collectively devoting upwards of $10 million to the race. Walker, as is his custom, is raising tons of money and has stuffed the state to the gills with campaign field offices. He’s one of the most disciplined politicians in recent memory, sticking resolutely to his message that Wisconsin is in better shape thanks to his policies, no matter what’s happening in Washington.

If he wins, Walker will be the last Republican governor from the so-called Tea Party Class of 2010 to remain in office. (New York Democrat Andrew Cuomo is the only other governor seeking a third term this year.) But he doesn’t concern himself with tending the flame for that particular strain of conservatism. Instead, he’s doing his best to put attention on state issues, seeking to remind people that they’re better off than they were eight years ago, while warning of the potential dangers of changing course. “It’s like amnesia,” he tells a group of supporters crammed into a small GOP party hall in Reedsburg. “People forget, before I was elected governor, Wisconsin was moving in a very different direction.”

Good economic news notwithstanding, Walker has to thread a needle. The state’s primary population centers, Milwaukee and Madison, will vote overwhelmingly for Evers (whose name rhymes with “weavers”). Walker needs to excite the conservative rural voters who came out and tipped the state narrowly for Trump and get them to turn out for this midterm, while not upsetting suburban Republican women who may have soured on Trump. When reporters ask Walker anything about Trump, the governor generally tries to insist that the issue at hand falls outside his jurisdiction.

Waukesha County, in suburban Milwaukee, is such an important source of Republican votes that The New Yorker ran a cartoon in 2016 showing Russian generals looking at a map of a divided red and blue America and being told, in a caption in Russian, “It’s all going to come down to Waukesha County.” There’s no way that Walker will lose Waukesha, but if voters there don’t turn out for him in the numbers he needs, in a year when Democrats in Madison and Milwaukee are highly motivated, Walker could well lose the state as a whole. “Democrats are going to get destroyed in Waukesha like they always do,” says Marquette University political scientist Paul Nolette. “But if the Republican numbers go just a bit down, Walker’s margin of error is so low that he needs those votes, and it’s plausible that those votes aren’t there.”

The Democratic candidate for governor, Tony Evers, says that Walker’s effort to adopt the mantle of “education governor” is an ridiculous assertion. (Alan Greenblatt)

It will be a considerable irony if Walker loses because a small percentage of his regular voters are put off by Trump. There’s still a plausible case to be made that, were it not for the rise of Trump, Walker would have been the Republican presidential nominee in 2016. He was almost uniquely acceptable back then to all major factions of the party. Walker, who will turn 51 four days before the election, combines the populist instincts of talk radio with the policy agenda of a free-market think tank. He initially polled well as a presidential candidate, particularly in Iowa, but ultimately his appeal as a Washington outsider was no match for Trump’s. Walker shut down his campaign in the fall of 2015, two months after its official launch.

He wasn’t a Trump guy. When he pulled the plug, Walker said he wanted to help clear the field so that a smaller number of candidates could “offer a positive conservative alternative to the current frontrunner.” Still, like nearly every Republican, Walker has been supportive of Trump as president, appearing regularly in Washington for working meetings and events. When Foxconn Technology Group announced its decision last year to build a $10 billion display panel plant in Wisconsin, the event was held at the White House. Trump later came to Wisconsin for the groundbreaking. “His connection to Trump represents his true colors as a right-wing politician, and that is not Wisconsin,” says Phil Neuenfeldt, president of the AFL-CIO in the state.

Walker himself concedes that “the left” is motivated this year by anger -- “more so at the president and others in Washington than me,” he says -- and notes that anger is a powerful motivator when it comes to increasing turnout. He wants his side to match that motivation, warning his followers at campaign stops that progressive forces from outside the state, such as a redistricting committee headed by Barack Obama and Eric Holder, as well as the leftist billionaires George Soros and Tom Steyer, would love nothing more than to defeat him. “The other side is angry,” says Brad Courtney, the state GOP chair, who believes this will be Walker’s toughest race.

For their part, Democrats have long complained that Walker is in the pocket of the Koch brothers and Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, pushing an agenda forged by big donors and the conservative American Legislative Exchange Council. They contend that Walker has decimated the state’s institutions. Spending on K-12 education is less than it was when the governor took office, despite his more generous recent budget. The university system has taken major financial hits, with several campuses cutting dozens of majors. The quality of Wisconsin’s roads ranks near the bottom nationally. It’s hard to find a state or county road that’s free of patches or potholes, which Democrats seek to rebrand as “Scott-holes.” That hasn’t caught on, but many voters, including lots of Republicans, complain that the highways are in bad shape. Walker adamantly refuses to raise the gas tax to pay for more maintenance or construction. With the incentive package that was offered to lure Foxconn topping $4 billion, plenty of people around the state say they’d rather use that money to pay for better roads.

The bulk of the new jobs and spending by Foxconn will happen in and around Mount Pleasant, which is located along Lake Michigan between Kenosha and Milwaukee. The company has made an effort to spread contracts around the state, and Foxconn has announced a $100 million gift to the University of Wisconsin’s main campus in Madison to start an engineering research project. Still, the farther you go from Mount Pleasant and southeast Wisconsin, the less popular the Foxconn deal seems to be. “Clearly, the economy should be an advantage for Walker, but complicating that for him is Foxconn,” says Nolette. “The deal he made remains quite unpopular.”

Despite the state’s low unemployment rate, it’s a Democratic talking point that too many people are having to work two or three minimum-wage or mediocre jobs to make ends meet. Job growth has plummeted, with the state ranking at the bottom for business startups for most of Walker’s current term. Democrats commonly use phrases such as “fed up” and “waking up” to describe voter reaction to Walker after so many years in office. No fewer than three former Walker cabinet secretaries have offered torrid criticism of the governor in recent weeks, accusing him of mismanagement and putting donors’ interests ahead of voters. All this leaves Democrats hopeful they can end what for them has been the nightmare of Walker’s regime. “It’s a different world this year,” says Ingrid Wadsworth, who chairs the Sauk County Democratic Party. “What’s happening at the national level has engaged so many people.”

But even some Democrats wonder if they have the right champion to unseat Walker. Evers has won the statewide post of superintendent of schools three times, taking 70 percent of the vote last year. He easily won the party’s gubernatorial nomination, aided by pre-primary polls that showed he could defeat Walker. Evers prevailed over a large field, but the candidates weren’t particularly well-known, even among Democratic voters. Evers wasn’t very well-known himself. A good number of primary voters declined to support him simply because they didn’t believe he would be a dynamic or charismatic enough alternative to Walker. “I just don’t think he has what it takes to beat Walker,” says Steve Sullivan, a small business owner in Janesville.

That sentiment is not uncommon. Evers, who will turn 67 the day before the election, is quiet, pale and mild. Even some of his supporters describe him as “bland” or “boring.” Walking along parade routes or past town festival tents, Evers is not the type of candidate who commands attention or grasps after every hand. He pushes back against descriptions of himself as placid, insisting that he’ll “fight like hell” for priorities such as increased education spending and expansion of Medicaid.

But if Evers is no glad-hander, he seems to get approached constantly for selfies by schoolteachers who say Walker has wrecked funding in their districts. Evers maintains that Walker’s effort to adopt the mantle of “education governor” is a ridiculous assertion. “He has done more to destroy public education in this state than any other governor,” Evers says.

Evers notes that education is an issue that concerns everyone, whether they tend to vote Democratic or Republican. While attacking Walker, he has tried to suggest that, even in a polarized era, it’s possible to find common ground on issues. He ran on a more moderate platform than his Democratic rivals, who veered left to endorse single-payer health care and free college tuition. Evers was the only candidate who didn’t pledge to cancel the deal with Foxconn (which, as a contract, would have to be renegotiated, Evers notes). Such stances might make Evers more acceptable to independents. He’ll certainly have no trouble attracting Democratic votes, simply by virtue of the fact that he’s not Scott Walker. “Fed up doesn’t even come close,” says Kiett Takkunen, an education consultant in Lake Nebagamon, describing her feelings about the governor. “It’s just deplorable that he is part of the whole Trump regime.”

Walker is seeking to turn the education issue against Evers. He says the Democrat’s complaints amount to posturing, since Evers himself described the governor’s last education package as “pro-kid.” As soon as Evers was nominated, Walker began attacking him over a case involving a science teacher who viewed pornographic material at school. The teacher was fired, but later reinstated. Evers says that state law made it impossible to revoke his license, and that he worked to persuade legislators to tighten sanctions. Walker counters that Evers should have gone after the teacher anyway and let the courts decide the matter.

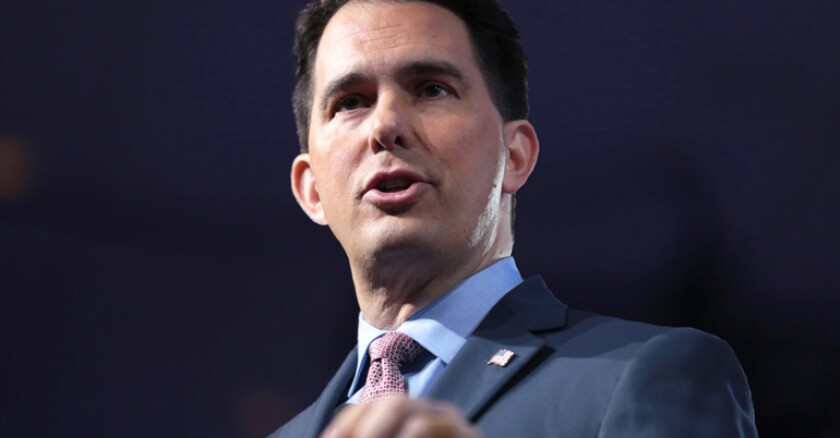

Touring meeting halls and dairy farms, Walker touts his record cutting income and property taxes to the tune of roughly $8 billion.(Alan Greenblatt)

To be hated by just under half the voters in the state is actually a positive accomplishment for Walker. After his failed presidential campaign, the governor’s approval ratings in Wisconsin sank into the mid-30s. Before running for president, Walker had governed as a conservative, but carefully stayed away from issuing pronouncements on divisive social issues. That changed as he sought to position himself for the Republican presidential nomination, decrying abortion and Planned Parenthood and publicly admitting he was flipping his position to take a harder line on immigration. Those moves cost him support within his own state.

After dropping out of the presidential race, Walker held listening sessions that eventually took him to every Wisconsin county. Education, health care and access to broadband came up repeatedly, helping to shape his agenda and campaign message this year and bring his poll numbers back up. “If we win again, it will really be a reminder that if you listen to what you hear from your constituents and you don’t nationalize everything, then that’s the winning recipe,” he says.

A centerpiece of Walker’s stump speech is talking about college students, how they had to leave the state to find jobs before his time in office, his own children included. Now his sons are back in the state and Walker says that the growth of employers such as Foxconn will keep more people around. Not just having a job but knowing your kids can get a job nearby -- and that you won’t have to get on a plane to visit grandchildren -- is “our ultimate American dream,” he says. He doesn’t tell voters much about specific policies he’d implement in a third term.

Walker may just be playing it safe. Or it’s possible that there simply aren’t too many mountains left to climb. As much as any state, Wisconsin under Walker has ticked off just about everything on the contemporary conservative checklist. Certainly, he will hunt for more regulations to eliminate, and he says there are plenty more taxes he can cut. But after eight years pursuing an aggressive agenda, there aren’t obvious big and splashy items such as right-to-work or voter ID laws left for him to tackle. “There are opportunities still,” says Paul Farrow, the county executive in Waukesha County and a former Republican legislator, “but, granted, we finished a lot of what are considered conservative goals.”

If austerity’s the policy, once it’s been achieved, there’s not a lot left to do. There certainly isn’t money for grand new initiatives, or even much for road repaving, which Walker’s fellow Republicans will press him to approve. But that may be the point. Wisconsin’s politics have long been a battle between progressives and a GOP faction once known as stalwarts, wealthy individuals and business interests who favored conservative policies. Progressives in Wisconsin had an impressive run, making the state a fountainhead for ideas such as workers’ compensation, unemployment insurance and Earth Day. Back in 1959, Wisconsin was the first state to pass a law allowing public workers to enter into collective bargaining. Walker has undone much of that.

In his new book, The Fall of Wisconsin, Dan Kaufman complains that Walker and his allies have decimated a state built on a Scandinavian sense of shared fortunes, turning it into “a laboratory for corporate interests and conservative activists.” What Kaufman views as a tragedy and a warning for the rest of the country, however, conservatives see as a triumph. And Kaufman concedes that rebuilding progressive institutions will be a lot harder than tearing them down. For all Evers’ promises to restore funding for schools and universities, the reality is that even if he’s elected, he will find it difficult to undo much of what Walker has done. The state Senate is in play this year, but the Assembly will remain in Republican hands. “This should be an incredibly easy win for the governor,” Farrow says, “but Wisconsin is a 48-48 state.”

If Walker does win, Farrow says he hopes that the governor’s third term will represent “continuance” and “steady governance.” That’s not an inspiring campaign slogan, but it may represent success. Walker has already refashioned the state in a much more conservative image. That will remain true even if he loses or, like many other third-term executives, has a hard time coming up with a grand new set of fresh and innovative ideas.