Councilman Russell Betts keeps track of the town’s economic health through informal barometers. When times are good, the roads are crowded. For quite a while, he says, “there wasn’t a traffic jam. People were just sitting at home, having a real hard time, not making money.”

For years, officials in Desert Hot Springs have looked for ways to increase the city’s median income -- about $34,000 for a three-person household in 2016, roughly $20,000 less than the national average. They have pursued better-paying jobs not only to reduce poverty, but also to revive spending at local businesses around town. About four years ago, Betts and fellow Councilman Joe McKee proposed a solution: Walmart had bought a parcel of land and planned to open a store in town. Why not require it and other big-box retailers to pay workers a “good wage”? At the time, the minimum wage in California was $9. Betts and McKee introduced a bill that would inch up the lowest hourly wage at big-box retailers incrementally until it reached $12.20. After that, pay would be tied to the consumer price index and would rise automatically with inflation.

Both Betts and McKee had concerns about the arrival of Walmart. They were aware of studies that found the company ultimately eliminated more retail jobs than it created. They knew Walmart often relied on part-time workers who got by on a mix of government benefits and near-minimum wage pay. Of course, many residents said they didn’t want to be forced to drive 10 miles to the nearest Walmart to go shopping. Having a store in town would save them grocery and gas money. “That may be true,” says McKee, “but there are economic consequences for other people, for people who own the small businesses, for the people working for the small businesses.”

The first time the council voted on the wage bill, in 2014, the result was a tie. The mayor at the time, Adam Sanchez, supported the bill but recused himself because he had received campaign contributions from a local union. The rest of the council was split. But a year later, another vote was scheduled at the first meeting after a new election.

Walmart bought a full-page ad in the local newspaper opposing the bill. A company spokeswoman charged that the proposal was aimed at blocking the store from coming to Desert Hot Springs. The company also got involved in the local council elections, paying for mailers that criticized candidates supporting a higher wage and praising candidates who agreed that it would scare away new businesses. Two pro-Walmart candidates won their elections, and at the next council meeting, the proposal was tabled. It was one of at least three occasions in the last 15 years in which a city came close to enacting a minimum-wage law for Walmart and other large retailers, but ultimately backed off.

Desert Hot Springs backed off its "good wage" ordinance after Walmart opposed it. (Flickr/Mrisasha)

Those fights about Walmart’s pay are emblematic of larger debates about the nature of low-wage jobs today, especially in the retail sector. Retail employees work about 31 hours per week, on average, according to recent data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. They have seen their hours decline steadily since the mid-1960s, when the average was 37 hours. Large employers in the retail industry use scheduling software to call in workers when business picks up and send them home early when it slows down. The workforce has to be available with little advance notice when these impromptu shifts open up. That may be a more profitable and efficient management practice, but it presents problems for workers who need predictable schedules for child care, doctors’ appointments or adult education.

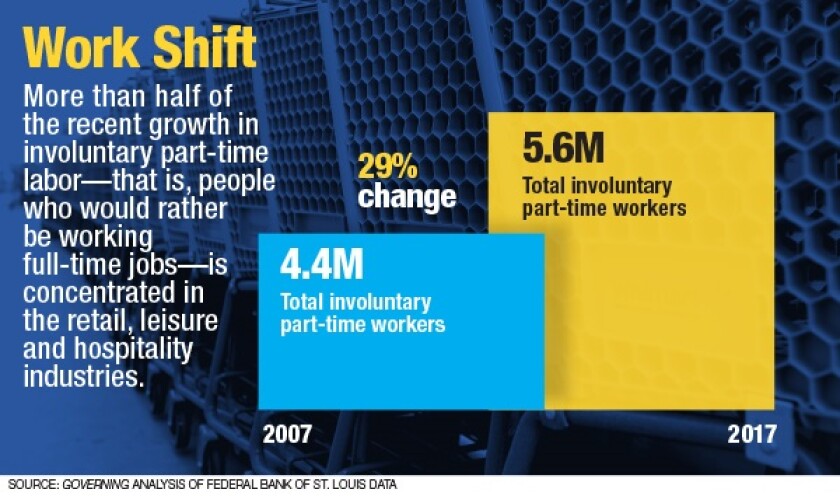

Economists call schedules like these “involuntary” part-time work, meaning that the employee would like to work full-time but can’t get the hours. Between 2007 and 2017, the number of people working involuntarily increased almost 30 percent, according to Lonnie Golden, an economist at Penn State University. While involuntary part-time labor is present in a range of sectors, more than half of the recent growth is concentrated in the retail, leisure and hospitality industries. The prevalence of involuntary part-time work could reflect lingering effects of the recession and a slow economic recovery, but Golden thinks it also represents a “structural shift” in the market. In other words, some of the missing hours might never come back.

“That is now a permanent feature of our economy,” says Zach Schiller, research director at Policy Matters Ohio, a think tank focused on reducing poverty. “In Ohio, we have a million part-time workers. It’s not as if all of those folks -- or a giant share of them -- are simply casual workers who are doing a part-time job because they’re moonlighting or something.”

As more workers have had to rely on low-wage, part-time jobs, the labor movement has pushed for state and local laws that require employers to pay higher wages, offer better benefits and provide more predictable schedules. Desert Hot Springs was one of the few places that tried to single out a specific big-box retailer like Walmart to provide higher pay. In both Chicago and the District of Columbia, slim majorities on the city councils passed ordinances requiring large retailers to pay more than the existing minimum wage. But in both cases, the mayor vetoed the legislation and the issue died.

It makes some sense that Walmart would be a target of these laws, given that it is the nation’s largest employer. Walmart occupies a special symbolic status, both because of its size and because critics have painted the Walton family that founded it as the face of growing income inequality in the United States. Most of the wage growth in the past four decades has been concentrated among the top 20 percent of wage earners, who saw real wages increase from $38 per hour to $48 per hour. By comparison, the bottom fifth of earners saw their real wages fall slightly over the same period. In 2016, the Waltons were wealthier than the bottom 40 percent of Americans combined.

But there are additional reasons why officials might scrutinize the company more than others. “They do set the standard in a lot of places,” says David Cooper of the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute. “If Walmart is raising pay, every other employer in the rural area where Walmart dominates is also going to have to respond. It does have outsize significance in that respect.”

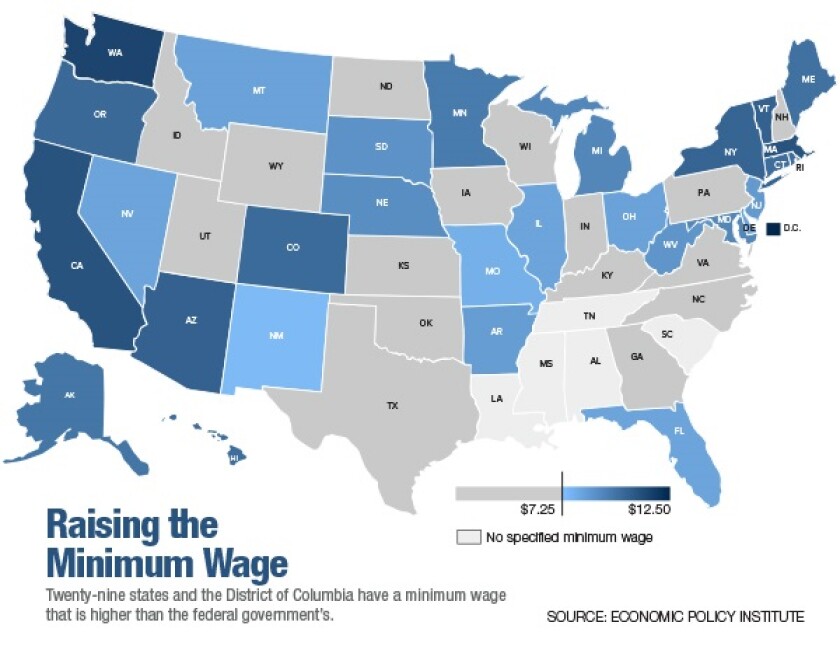

Nonetheless, most places haven’t tried to hold Walmart or other large retailers to a higher standard. Instead, states and localities have enacted across-the-board minimum-wage increases. Since 2014, at least 21 states and the District of Columbia have raised their minimum wage. Dozens of cities and counties have passed laws requiring an even higher local minimum wage. (While those state and local laws do not explicitly target big-box retailers, some do set a higher minimum pay for the largest employers.)

During the same period, nine states and nearly 30 localities have mandated that employers provide paid sick days. This year, both the state of Maryland and the city of Austin, Texas, enacted laws requiring paid time off for illness. In January, New York became the fourth state to establish a family leave program for parents of newborns, funded through employee payroll deductions. D.C. passed a similar law at the local level and plans to begin providing up to eight weeks of parental leave by 2020.

While city halls and state legislatures continue to consider wage and benefit laws, unpredictable schedules and the insufficient hours that often come with them are becoming the next area of focus for labor advocates. So far, Oregon and a handful of cities, including San Francisco and Seattle, have enacted laws requiring employers to post schedules two weeks in advance. Many of these laws also mandate that employers offer additional hours to current part-time workers before they bring on new hires. “All of these issues work together and they’re all different parts of the same story,” says Andrea Johnson, an attorney who oversees state policy at the National Women’s Law Center. “If you’re not getting anywhere near full-time hours, then a $15 wage doesn’t really mean much to you.”

Feeling pressure from organized labor and public opinion, some large retailers are starting to raise wages voluntarily. Target, for example, plans to raise its minimum hourly pay to $15 by 2020 and has announced two pay bumps since last fall. Walmart has also raised wages, though not at the same rate. When Doug McMillon became CEO of Walmart in 2014, he addressed criticism about the company’s low pay and promised to raise wages in the future. “In the world, there is a debate over inequity,” he told a television interviewer. “Sometimes we get caught up in that and retail does in general.”

The TV interview was significant because it was the rare moment when company leadership even acknowledged concerns about pay. McMillon was “giving a nod to all of the campaign work out there that was raising all of the issues around inequality and the damage that that was having on our economy,” says Daniel Schlademan, co-director of OUR Walmart, a group that has organized protests at company stores across the country with help from the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union.

Walmart and other big retail companies say critics ignore the fact that low-wage workers often start with gaps in the foundational skills of reading, writing and working with numbers. “Walmart in particular and retail in general has always been a great access point for people into the workforce,” Walmart Foundation President Kathleen McLaughlin told an audience of governors recently. “Very low barriers to entry, people can come in, get a good start, they can acquire skills on the job, learn what they need to do to move up,” she said.

For many, those first jobs are opportunities to advance within the organization. McMillon began his career at Walmart by unloading trucks, and three-quarters of the company’s store managers started as hourly workers. “But it may not be the experience of every person who came and showed up for a job at Walmart,” McLaughlin conceded. “We said to ourselves, ‘How can we make that more systematic?’”

(Shutterstock)

As a result, Walmart has invested more than $2.7 billion in higher wages and training for employees since 2016. The company has opened more than 200 academies and trained more than 250,000 workers in skills necessary to move up in their careers, such as inventory management and customer service. The Walmart Foundation has donated $100 million to workforce development programs aimed at “upskilling” workers in the retail and service sector more broadly.

Although those investments came after unions rallied around wages and benefits at Walmart, the company does not credit outside pressure for the changes. “I don’t know that it was in response to a particular criticism,” says Tricia Moriarty, a spokeswoman for the company. Instead, she says, the company saw a business case for investing in employee training. “It’s such a return on investment because associates are more engaged. We’re seeing higher retention among our academy graduates and the people they lead. It’s pretty transformational.”

Walmart’s most recent wage boost lifted the pay of all hourly associates from $10 to $11. At the same time, the company liberalized its parental leave policy and provided up to $1,000 in one-time bonuses for some employees. The company says it already had plans to increase wages and parental leave, but credited corporate tax cuts in the 2017 federal tax law for accelerating those plans. Another reason may be that big-box retailers are competing to attract and retain workers at a time when unemployment is at its lowest point nationally in more than a decade.

Walmart critics note that even after the increase, a full-time employee at one of the company’s stores making $11 an hour would still be below the national poverty line for a family of three. “We’re making progress, but we still have a ways to go,” says Schlademan. “Our belief is still that the minimum wage at Walmart should be $15.”

More than two years after the “good wage” ordinance died in Desert Hot Springs, Councilman Betts is more optimistic about the local economy. “The town is really busy right now,” he says. He notices more customers at restaurants and the UPS Store, more people getting haircuts at the local salon and more commuters leaving for work in the morning.

One thing hasn’t changed, though. The city still doesn’t have a Walmart. After the company won its campaign against the wage bill, it gathered petition signatures to bypass the regular development approval process, which would have let the city require Walmart to change its site plans to lessen the negative impacts on traffic and the environment. Before the question could go on the ballot, the city council voted to approve Walmart’s initial application without the typical negotiation and impact fees.

But then Walmart announced that it wouldn’t be building in Desert Hot Springs after all. “It showed how large organizations could bully small towns,” says Councilman McKee. “There are people in town who continually ask why isn’t Walmart here and blame the city council. We’ve passed something saying they can come. What more can we do?”

The pullback from Walmart is consistent with a nationwide strategy in which the company isn’t trying to expand its physical presence the way it was a couple of years ago. When it announced wage increases for associates in January, it also closed 63 of its Sam’s Club stores. In recent years, it has backed off plans to open stores in New York City and add locations in Washington, D.C. “It does feel like many of the battles over Walmart coming into cities have not been as front and center as in the past,” says Schlademan. “Their focus now is on trying to compete with Amazon online and [go] where retail is heading.”

Even without Walmart, new economic development in Desert Hot Springs is taking place. In 2014, it became the first California city to permit large-scale commercial cultivation of medical and recreational marijuana. The industry is expected to bring in 2,000 jobs and $4 million in tax revenue a year. (The city’s entire annual budget is $16 million.) Betts is quick to manage expectations -- it’s not as if the city’s poverty has been alleviated -- but he’s happy to see more white-collar jobs, including opportunities for bookkeepers and human resources professionals, being created as a result. And even though a big-box wage bill never passed, the local marijuana businesses have voluntarily offered a base pay above the state or federal minimum wage. New hires at some of the grow facilities start at about $15 an hour.