Rather than a single revenue department, California uses three separate agencies to manage different taxes. One of those agencies, the Board of Equalization (BOE), collects sales and property taxes, along with many smaller revenue sources such as levies on jet fuel. Now it’s taking on the new role of collecting marijuana taxes. But even as its mission continues to expand, the BOE appears to be badly mismanaged.

A recent audit from the state Finance Department found that the BOE’s elected board members have been directing civil servants to work on pet political projects. It also found that those board members, who aren’t supposed to receive political contributions exceeding $250, have been known to accept thousands in bundled donations of $249 from companies who have business before them. And although the BOE is supposed to meet in open, quasi-judicial hearings, recent legislative testimony revealed members have met privately with parties who were appealing their tax assessments, never reporting the content of those conversations. “The testimony indicated that board members were inappropriately influencing staff members in the performance of their duties,” says state Sen. Steven Glazer.

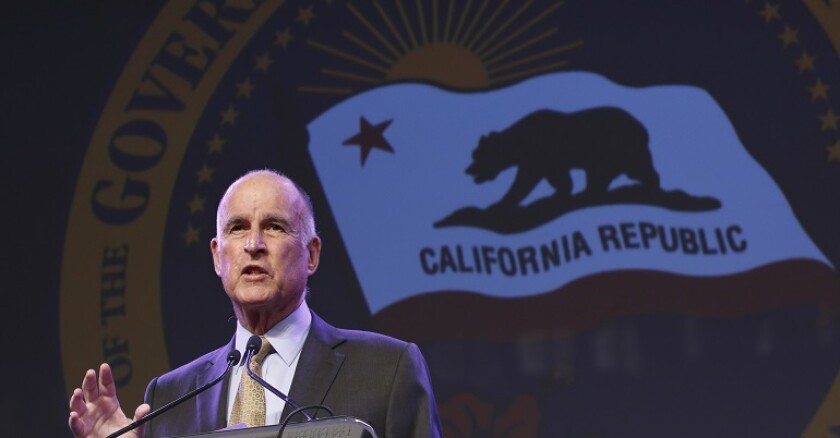

The audit prompted Gov. Jerry Brown to temporarily block the board’s ability to hire or make large purchases. He’s also requested a fresh investigation from the state’s Justice Department, and called on legislators to find a way to overhaul the BOE. Meanwhile, members of the board have joined with outsiders in putting forward their own proposals to revamp parts of the agency. “Clearly it needs to be run significantly better,” says state Rep. Phil Ting. “They have trouble answering even the most basic budget and systems questions.”

For all its faults, however, no one in Sacramento is convinced that big changes are about to hit the agency. Many powerful interests in the state like things the way they are. Those with inroads to the board are able to wheedle favorable opinions on behalf of their clients. Board members enjoy pretty good perks, including sizable staffs. The state controller sits on the board, but other members, who are elected directly by voters in four separate districts, include ex-legislators who have chummy relations with their former colleagues. “It’s those relationships, I believe, that have kept reforms from happening,” says state Sen. Jerry Hill.

The Board of Equalization was set up back in the 19th century as a way of dealing with problems caused by county assessors. Back in those days, taxes were proportionately higher in mining counties than grazing counties. Hence the need to “equalize” taxes.

That function long ago ceased to be important, but the board kept taking on more work. Collection of income taxes, for example, falls under the Franchise Tax Board, but the BOE still adjudicates disputes about those taxes. “With this elected tax board, you’ve got a group of people with really very little knowledge or expertise about taxes, who don’t create any useful body of precedent for people to understand taxation,” says Daniel Simmons, an emeritus law professor at the University of California, Davis. “There’s really no way to fully know how the law will be interpreted and applied.”

Over the years, countless commissions and studies have recommended that state tax collection be consolidated into a single revenue department accountable to the governor -- which is how most states do it. But killing off the BOE would require a constitutional revision approved by voters. That isn’t likely.

Still, a summoning of political will could create some meaningful changes to the agency. The board, if it were so inclined, could even fix things, says Sen. Glazer. “This could be resolved with better board policies and a CEO who insists on respect for the chain of command of his office,” he says. “But it’s a big question.”