Prince Harry’s “long-awaited” memoir, Spare, is anything but. Its 410 pages are causing a big stir in both Britain and the United States and it must be a source of great angst within the royal family. It’s hard to know whether his publisher urged him to ratchet up or ratchet down his conflict with his father, his brother, his sister-in-law, and his late grandfather, but the result is a memoir that will damage not only the royal family, but perhaps even the future of the English monarchy. The idea of royalty depends on the illusion that these folks are more glamorous, more elegant and refined, more dignified than the rest of us. If they turn out to be just like the rest of us, but on a blank check expense account, it will prove difficult to maintain the fairy tale.

The memorial service for Lisa Marie Presley was held at Graceland, the compound made famous by her father, Elvis.

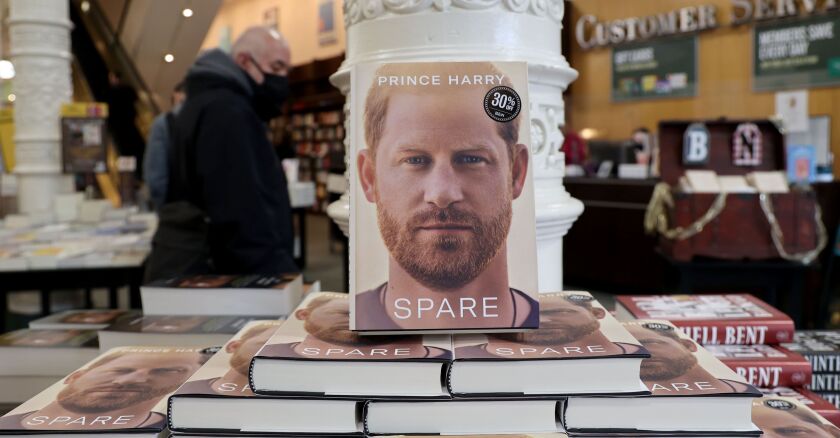

Spare, Not Heir

Prince Harry grew up as the son of the heir apparent to the British throne and one of the most famous women of the 20th century, Princess Diana, who was in some ways hounded to death by the media on Aug. 31, 1997. She was just 36 years old. Both of Harry’s parents’ lives were messy, and their struggles were played out in the popular press, which in England is particularly intrusive and salacious. The constraints of what the royal family calls The Firm are so confining that no one with an ounce of spontaneity or vitality can reasonably be expected to conform without fallout. Imagine a life of cutting the ribbons at bridge openings and new hospital wings.

(Courtesy of Prince Harry and Meghan, The Duke and Duchess of Sussex/Netflix/TNS)

(Random House/TNS)

Teddy’s Princess Alice

She was soon called Princess Alice. Her every move was reported by the American press, which hadn’t had a real White House family to report on since the Lincolns half a century earlier. Her favorite color became universally known as “Alice blue.” She got married in the White House (Feb. 17, 1906). She was a strong-willed and somewhat rebellious teenager and young woman. She smoked (against her father’s express prohibition). She drank spirituous liquor. She drove in jalopies at breakneck speed (25 mph) sometimes without a proper male escort. She flirted with a wide range of men, some of them married. She was sufficiently annoying that each of her parents finally resorted to exasperation.

At the close of the White House wedding — in which nothing had been up to Alice’s impossible standards, including the dress — her stepmother Edith kissed her on the mouth (apparently a first) and said, “We’re glad you are going, you have never been anything but trouble.”

Theodore Roosevelt, perhaps with more good humor than Edith could muster, responded to a friend who asked him why he didn’t restrain his daughter’s wilder antics, with his famous: “Look, I can be president of the United States or I can control Alice. I cannot possibly do both.”

Ah, but Alice could give as good as she got. She once said, “My father wanted to be the bride at every wedding, and the corpse at every funeral.” In fact, her funny and snarky statement was more accurate than her father’s. TR was able to exert some control over her behavior, though she had trust funds that made her impervious to any financial threats from her parents.

Roosevelt actually trusted her political instincts, relied on her to gauge the mood of Congress (she was married to Ohio Rep. Nicholas Longworth), and engaged her to perform some important tasks on behalf of his administration. The very first sentence of her autobiography reads, “I can hardly recollect a time when I was not aware of the existence of politics and politicians.”

Alice in a Man’s Land

Needless to say, Alice was the most exuberant member of the delegation. She smoked, jumped into the ship’s swimming pool with her clothes on, took hula lessons in Hawaii, and plunked away from the deck at passing “targets” with her pocket revolver. She said it was her “pleasurable duty to stir them [Taft and the self-important members of Congress] up from time to time.” Decades later, when Robert F. Kennedy playfully chided Alice for the indecency of jumping into the pool fully clothed, she shot back that it would only have been indecent if she had stripped off her clothes first.

Everywhere they went, she was showered with gifts (“I was a frankly unashamed pig,” she admitted). In Japan she managed to get in a satiric jab at the over-sized secretary of war, one of her father’s closest allies. Observing an exhibition of sumo wrestling she said, with her usual insouciance, that the contestants were just “huge, fat men as big as Secretary Taft himself.” Taft, for his part, was accustomed to fat jokes. While he was serving as the American proconsul in the Philippines, the 300-pound diplomat cabled to then Secretary of War Elihu Root that he had spent the day in a most delightful horseback ride. Root replied, “Referring to your telegram — how is the horse?”

Alice may be seen as a victim of Victorian social restraints. She had her father’s outsized intelligence and drive, but nowhere to put them. A woman of her social sphere — and the daughter of a president to boot — could not then be a Wall Street broker, a pharmacist, a college president, a U.S. senator, or a Supreme Court justice. She could maybe be a nurse or a teacher or a professional philanthropist. When we observe 21st-century cultures that have not yet emancipated women, we say they are wasting 51 percent of their talent. Just imagine if America had been able to find something extraordinary for Alice Roosevelt to do with her capacities.

In China, Alice had an audience with the Empress Dowager Cixi, who ruled the nation because her adopted nephew was too weak to resist her power. Alice wrote, “The Empress Tsz’e Hsi [Cixi] ranks with Catherine of Russia and Elizabeth of England, with the Egyptian Queens Hatshepsut and Cleopatra, as one of the great women rulers in history … . The character and power of the Empress were palpable and though at the time we met her she was over 70, one felt her charm.” It would not be until — well, never yet — that a woman presided over the United States of America.

Alice wrote an autobiography, Crowded Hours, published in 1933, long after her notorious father was dead, and though it was in some ways startlingly candid, she did not use it to settle scores, strike back at her family, or whine about life. She dined with every American president through Jimmy Carter. She barely regarded John F. Kennedy as being worthy enough to be president. She called Washington, D.C., “a town of successful men and the women they married before they were successful.” And most famously she said, “If you have nothing good to say about anybody, come sit by me.”

Who knows what this remarkable woman might have achieved in a country where women had equal opportunities with men? Harry Windsor would have benefited from reading her autobiography.