It is not, however, the first time that the peaceful transfer of power has faced serious challenges for the incoming President or for the nation. The strength of the American system of four-year presidential terms is also at times its weakness. There is inevitably a period of uncertainty — even interregnum or governmental suspension — between the quadrennial November election and the installation of the next administration the following year. At one time that period lasted from early November until March 4 of the following year. Beginning with The New Deal, the interim was reduced to eleven weeks, until Jan. 20, to make it easier for the incoming President to take control and address pressing national problems.

Under a parliamentary system, by contrast, the ruling party and the Prime Minister can remain in power all the way through a crisis period, and the permanent bureaucracy in a British Commonwealth country of dedicated civil servants who provide nonpartisan continuity irrespective of party politics, provides for a stability that is more dependable than our system in which every change of administration involves a dramatic sweep of office holders and their replacement by some 4,000 presidentially-appointed individuals who suddenly find themselves directing essential services of the United States government.

It might be useful (and perhaps comforting) to examine a few of the more momentous transfers of power in American history.

Sour Grapes and Midnight Appointments

John Adams more or less inherited the presidency from George Washington in 1796, and nothing that he found on his desk surprised him. It was a three-mile-per-hour world and by our standards, not much was at stake. Since the Constitution makes no mention of a presidential Cabinet and this was the first transfer of power in U.S. history, Adams thought it made sense to retain Washington’s four-member Cabinet intact. This was the greatest mistake he made as president. The Cabinet members proved to be far more loyal to the “shadow president,” high Federalist Alexander Hamilton, who was now an attorney in private practice in New York, than to the duly elected president John Adams. Most of the problems of Adams’ one-term presidency stemmed from this decision. Adams rightly understood that continuity matters in a system that can change its leader every four years, but he underestimated the mischief a disloyal Cabinet can pursue.Thomas Jefferson called the election of 1800 the “Second American Revolution,” and he cheerfully discarded every senior official of the Adams administration. He believed that he was returning the country to the ideals of 1776 and that the “reign of witches,” as he called twelve years of Federalist rule, was now thankfully over. Embittered by his defeat, Adams had used the interim between November 1800 and March 4, 1801, to do Jefferson some mischief. He filled a number of judicial offices with anti-Jeffersonians, people Jefferson later said were “among my most ardent political enemies, from whom no faithful cooperation could ever be expected.”

The most important of these “midnight appointments” was Chief Justice John Marshall, a Virginia Federalist and a determined nationalist who dominated the Supreme Court for the next 34 years and, in doing so, interpreted the Constitution to give it more centralized authority than it might otherwise have achieved. The only surprise Jefferson found on taking office was that not all of Adams’ last second appointees had actually received their legal commissions. Jefferson told his Secretary of State James Madison simply to discard commissions that had not actually been delivered to their intended recipients. This led one of the thwarted appointees, William Marbury, to sue for his promised job under something called a writ of mandamus. That minor legal action produced the historically important Supreme Court decision in Marbury v. Madison (1803), which among other things declared that the Supreme Court would be the final arbiter of what was and was not constitutional in the American system.

Presidential Assassinations - Lives and Administrations Cut Short

The sudden death of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, just one month into his second term, lifted Vice President Andrew Johnson into the presidency. Lincoln barely knew him. Probably nobody could have followed Lincoln successfully, but Johnson, a conservative from Tennessee with deep sympathies for the former Confederacy, refused to enforce the various racial Reconstruction measures passed by the victorious Union Congress. Johnson actually opposed theFourteenth Amendment, designed to prevent discrimination against African Americans, and worked publicly against its ratification. Johnson’s obstinacy eventually led to his impeachment, the first in American history. He escaped conviction in the Senate by a single vote.

President Andrew Johnson

The Johnson debacle should have taught all subsequent Presidents that it is essential to choose a running mate who has the capacity to take the helm on a moment’s notice, and who accepts the governing philosophy of his predecessor. Unfortunately, that is not always the case. Thanks to the breakdown caused by Lincoln’s assassination and Johnson’s unfitness for a post-Lincoln presidency, millions of African Americans were essentially re-enslaved by systematic disenfranchisement and the Black Codes that were adopted all over the South following the adoption of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments.

McKinley and Roosevelt: Caretaker Succeeded by Activist Reformer

William McKinley chose Theodore Roosevelt to be his running mate in 1900 against his better judgment. He regarded Governor Roosevelt as an aggressive and impulsive lover of conflict, but he also knew that TR was a new national hero, after San Juan Hill in Cuba, that he would campaign heroically for the McKinley-Roosevelt administration, and that he was an exceptionally talented politician. When McKinley died on Sept. 13, 1901, from a bullet wound sustained a week earlier in America’s third assassination, Roosevelt solemnly pledged, “In this hour of deep and terrible national bereavement I wish to state that it shall be my aim to continue absolutely unbroken the policy of President McKinley for the peace and prosperity and honor of our beloved country.”

Teddy Roosevelt (Library of Congress)

Roosevelt may have believed those words when he spoke them in Buffalo, but he soon forgot McKinley altogether and charted his own strenuous course, which included the Panama Canal; trust-busting; intervention in a national anthracite coal strike; sending the entire U.S. fleet on a round-the-world friendship cruise; intervention in the Russo-Japanese War (for which he won the Nobel Prize); and setting aside 230 million acres of the public domain as permanent National Park, National Monument, National Wildlife Refuge, National Forest and National Game Preserve, the greatest conservation record of any president. McKinley was one of the dozens of caretaker presidents (the norm, especially then). Roosevelt was an activist, a reformer and a change agent. Ironically, TR presided over seven years and 171 days of peace and prosperity. Nevertheless, McKinley would probably have been aghast had he witnessed his successor’s activist administration.

What Would JFK Have Done?

In the weeks before his assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was wrestling with the intractable problem of Vietnam. He had always been reluctant to engage U.S. combat troops there. The situation was deteriorating quickly, and the American “advisers” and special forces were unable to protect South Vietnam from being overrun by the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese raids. We don’t know what JFK would have done had he lived (it is one of the most hotly debated questions of American history), but he seemed to be unwilling to commit tens or hundreds of thousands of ground combat troops to the post-colonial conflict.

Lyndon B. Johnson sworn in as President of the United States on Air Force One following President John F. Kennedy's assassination. Nov. 22, 1963. (LBJ Library)

Lyndon Baines Johnson was less ambivalent about a deeper American engagement in Vietnam. Inheriting the presidency under such terrible circumstances, he thought he was pursuing the policy his martyred predecessor would have chosen in 1964-65, and he said, unambiguously, that he was not going to be the first president in American history to lose a war. We can never really know, of course, but if JFK had lived and been re-elected in 1964, the next decade, the most horrific in post-World War II history, might have unfolded differently. The colossal tragedy of Vietnam was the result of a number of miscalculations, but the discontinuity attendant on sudden transfer of power is surely a significant part of the story.

Harry Truman and the Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb

The greatest surprise in American transition history came to Harry S. Truman on April 12, 1945, just hours after President Franklin Delano Roosevelt died at Warm Springs, Ga. FDR did not choose Truman as his running mate in 1944 for his capacity to take the reins at a moment’s notice. They had very few meetings between the election and FDR’s death. Just hours after he was sworn in as the 33rd president of the United States, Truman was informed of the Manhattan Project, the $2 billion super-secret initiative to create an atomic bomb in time to affect the outcome of the war. This was literally the first he had heard of it — the greatest weapon of mass destruction in human history.Well less than four months later President Truman would have to decide six vital questions, any one of which would have defined a caretaker presidency. 1) Whether to use it on Japan now that the war in Europe was over. It had been developed for use against Adolf Hitler, who was thought to be pursuing the same technology. 2) Whether to detonate it on a lonely atoll in the Pacific as a demonstration bomb and invite representatives of the world community, including Japan, to witness its devastation, or whether to drop it on Japan. 3) Whether to warn the Japanese first or just drop it unannounced. 4) Whether to target an exclusively military installation, a civilian population or a combination of the two. 5) Whether to tell our allies about the weapon or protect it as a strategic secret. 6) How long to wait between the first and subsequent uses of the weapon, in order to give Japan the opportunity to reassess its predicament and its war strategy?

In his usual blunt, “the buck stops here,” manner, Truman later said he had no choice but to use the atomic bomb against Japan, because if he saved a single American life in doing so, he had a moral obligation to give the go ahead. He asked how he would be able to explain not using a weapon that could end the war quickly to parents of young men who died in taking the main Japanese islands using pre-atomic weapons.

Nagasaki after the dropping of the atomic bomb in 1945. (National Archives)

The literatureabout the decision to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki is immense. To this day you can touch off a fierce argument in a public forum about this issue. One question that gets plenty of attention is what FDR would have done had he lived. He had known about the possibility of an atomic weapon since Aug. 2, 1939, when Einstein wrote his famous letter indicating that it was a real possibility given what had just become known about the energy released by the splitting on the atom. FDR had had six years to think about the implications of the atomic bomb and a range of scenarios about how the war might end on both of its theaters. Some of the evidence suggests that FDR was softening in his attitude toward Japan, that his views were softening generally as his vital energies waned, and that he might well have chosen a deployment regimen of greater warning to Japan and other world powers, might have brought the Soviets in to the deliberations, might have preferred a Pacific demonstration before use over Japan, and might have waited considerably longer between bombing runs (Aug. 6 on Hiroshima; Aug. 9 on Nagasaki).

We cannot know for sure, of course. But it is certain that Harry Truman suddenly inherited one of the most consequential decisions in the history of the world, that he had to make his decisions about the use of the atomic device without the benefit of a careful and sustained debate at the highest levels of his brand-new administration, and that he may not have been fully aware of the implications of his decisions in the hurly burly of the last months of the war. I’ve read much of the literature of the decision to use the atomic bomb carefully, and though historians can never know for sure, I do believe that FDR might have made quite different choices in the summer of 1945.

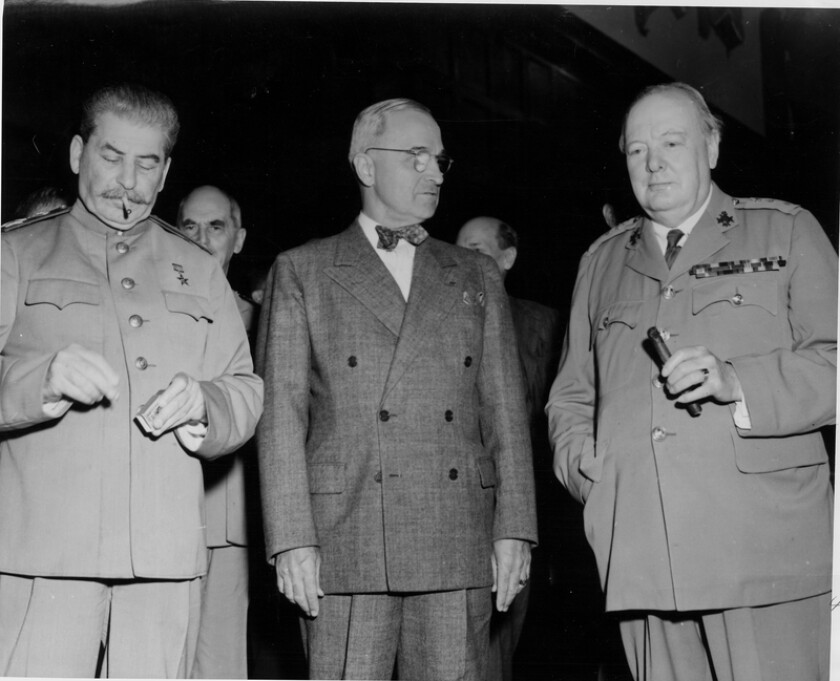

We do know with certainty that Winston Churchill was worried that FDR was becoming too soft and too humane as the war strained towards its inevitable conclusion. What is equally certain is that our system of government — with an interregnum between administrations, often of fundamentally different political philosophies, and the ways in which most vice presidents have been left or kept in the dark while their presidents lived — creates some very significant issues, especially now that the world travels at the speed of light or in the bomb-bay of a B-29 Superfortress.

Stalin, Truman and Churchill. (Harry S. Truman Library & Museum)

There are other such moments in presidential transition history, both the sudden kind as after deaths or assassinations and the more typical kind as when George H.W. Bush yielded graciously to Bill Clinton or Barack Obama yielded responsibly to Donald Trump. The ways in which the Trump administration has resisted a smooth and cooperative transition, especially in the middle of the greatest public health crisis in American history, inevitably complicates the next administration’s work, and it may make it more difficult for the national government to hit the ground running. A number of foreign policy and national security experts have argued, too, that an unsmooth transition without full cooperation could make the United States vulnerable to threats to our national security that most of us never hear about. It also probably violates the Presidential Transition Act of 1963, which laid down protocols for a smooth and orderly transition. That law specifically said that “any disruption occasioned by the transfer of the executive power could produce results detrimental to the safety and well-being of the Unite States and its people.”

This is not the first time a new President has faced the challenge of discontinuity between administrations. Some of this is inevitable given the Founding Fathers’ determination that no single presidential term shall last more than four years, not even in times of domestic or international emergency. A history of what has fallen through the cracks because of presidential discontinuity would make for fascinating and sober reading. The capital C Constitution has no remedy for this problem, but the way we have come in 235 years to “constitute ourselves,” in other words the lower-case c constitution, provides procedures and mechanisms to lessen the vulnerability of presidential transitions. But what we are learning in December 2020 is that these unwritten norms are only as strong as the individuals who are meant to embody them, and when an individual decides to carry disruption and dismay to the level of nihilism, everyone who is committed to peaceful and smooth transfers of power has to do some extraordinary scrambling.

For more of Clay Jenkinson's views on American history and the humanities, listen to his weekly nationally syndicated public radio program and podcast, The Thomas Jefferson Hour. Clay's most recent book Repairing Jefferson's America: A Guide to Civility and Enlightened Citizenship is available on Amazon.com.