Traffic safety advocates point to two main factors behind the increase. One is the improving economy, as Americans are traveling more. The other likely culprit is the wide variance in state laws that, according to advocates, aren’t doing nearly enough to curb fatalities.

When the economy took a downturn, so too did traffic deaths. But economic recoveries generally coincide with higher fatality rates because families have more discretionary income, take extra vacations and travel more on weekends. Parents also tend to purchase more cars for teenagers, who face the highest risk of accidents.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) reports that the vast majority (94 percent) of fatal crashes are caused by human error. So the agency has looked to bolster measures that influence motorists’ behavior. In November, NHTSA Administrator Mark Rosekind called on states and localities to “reassess whether they are making the right policy choices to improve highway safety.”

But most state legislatures have showed little interest in strengthening traffic laws in recent years. Some, in fact, have raised maximum speed limits or considered repealing motorcycle helmet laws. “We’ve reached a plateau,” says Jonathan Adkins, executive director of the Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA). “States have generally improved their safety laws, but we haven’t got them to take that next step.”

One of the most effective strategies in saving lives is getting motorists to buckle up. While seat belt use has climbed significantly over the past several decades, states without strict seat belt laws lag behind. The 34 states that treat failure to wear seat belts as a primary offense report average seat belt usage rates about 10 percentage points higher than those in other states. If everyone wore a seat belt, according to NHTSA estimates, an additional 2,800 lives could have been saved in 2013.

705.png

Helmet laws for motorcyclists also have been a priority for public health and safety advocates. Nineteen states currently require all motorcyclists to wear helmets, while most others maintain more limited laws. No state enacted a new helmet law last year, and lawmakers in 10 states introduced legislation that would have repealed existing helmet mandates. About 96 percent of motorcyclists wear helmets in states where all riders are required to wear them, compared to just 51 percent in other states, according to a 2014 NHTSA survey.

Ignition interlock devices have been shown to reduce repeat DWI offenses by 70 percent, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Half of the states mandate installation of the devices on vehicles for all drunk driving offenders. These motorists account for about a third of traffic deaths nationally.

Speeding plays a role in more than a quarter of all fatal crashes. States have continued to increase maximum speed limits, however, and a handful have statewide maximum speeds of 75 mph or more.

Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, a national group that lobbies Congress and state legislatures, rates states on whether they’ve passed laws covering seat belts, teen and impaired driving, and a dozen other safety concerns. In the group’s latest report, Delaware, Illinois, New York and Oregon had adopted the most safety laws (12), while six states had enacted five or fewer of the recommended laws. The least restrictive traffic laws are found in predominantly rural and Western states. “When the deaths were going down, people were quick to pat themselves on the back,” says Jackie Gillan, the safety group’s president. “There is still a major unfinished agenda.”

Lawmakers’ willingness to pass additional traffic safety mandates doesn’t always align with political ideology. In general, though, those who oppose tighter rules view them as unnecessary government intrusion. “Government exists to protect us from each other, not to protect us from ourselves,” said Maine Sen. Eric Brakey, as he argued last year for a bill repealing the state’s primary seat belt enforcement law. The bill did not pass.

Gillan says sanctions passed by Congress have proven more effective in pushing states to pass safety laws than incentive-based grant programs. A law enacted in 1995, for example, withheld federal highway funds from states that failed to pass “zero tolerance” laws making it illegal for those under age 21 to drive with small amounts of alcohol in their system. Every state had adopted these laws by 1998.

In addition to state laws and the economy, a litany of other factors push traffic fatalities up or down. Warmer weather typically contributes to higher death totals. Some attribute changes in driving habits to fluctuations in gas prices.

Increasingly negative public perceptions of law enforcement and the proliferation of body cameras may also be affecting the way laws are enforced. GHSA’s Adkins suspects that, in some areas, police are less likely to make traffic stops for minor violations than before the recent series of controversies over aggressive police behavior, in part because of concerns for their safety.

New technology and automated vehicles have further shown promise in enhancing traffic safety, Adkins says, but they’re still a long way off.

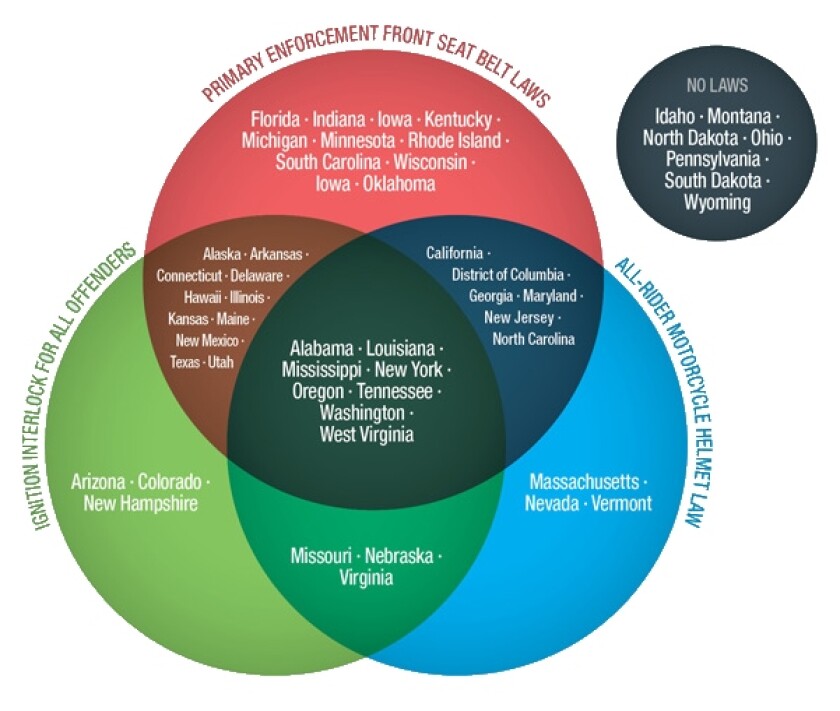

State Traffic Safety Laws

Three of the top measures that federal officials and safety advocates have called on states to adopt include primary enforcement of front seat belt laws, requiring all motorcyclists to wear helmets and mandating ignition interlock devices for all convicted drunk driving offenders.

NOTE: Some states (not shown) have variations of these laws that do not apply to all motorcyclists or DUI offenders.

SOURCE: Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, current as of December 2015.