It’s a startling development in an area that, despite being hemmed in on a narrow strip of land between the Everglades and the Atlantic Ocean, depends almost entirely on cars.

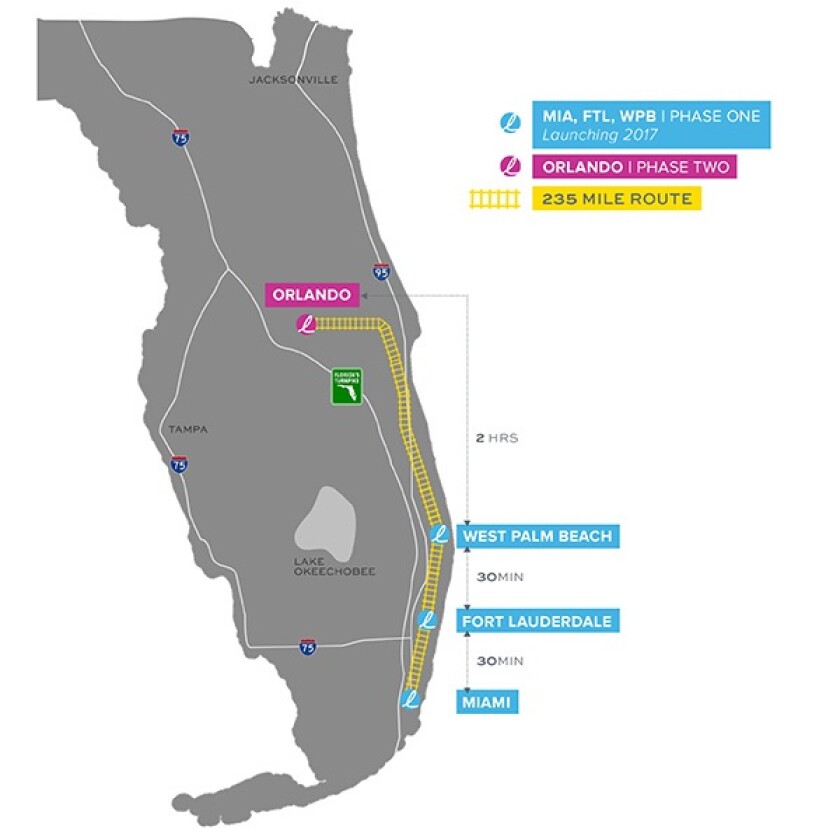

But what’s more startling is how the service is being paid for. It isn’t the state of Florida or the municipalities along the route that are putting up most of the funds; it’s a private company that’s convinced it can make money by building and running the $3.1 billion project largely on its own. By 2020, the company, named All Aboard Florida, hopes to extend its “Brightline” service all the way to the Orlando airport, 168 miles north of West Palm Beach. With top speeds of 125 mph, the train could take passengers from Orlando to Miami in a relaxed three hours, rather than the four stressful hours it usually takes in a car.

For many transportation and infrastructure advocates, Brightline is exactly the right project for the current political and financial environment. Congress has repeatedly balked at raising new taxes or finding long-term sources of money to pay for existing infrastructure needs, and most states don’t have the financial wherewithal to launch ambitious new public works projects. That leaves deep-pocketed private investors as a crucial source of funding to build much-needed infrastructure. For conservatives, relying on the private sector represents a wager that what gets built can be supported by the market rather than by tax dollars. The fact that Brightline will be the first privately built passenger railroad to open in the United States in decades means it will garner plenty of attention.

But before Brightline can serve as a model for infrastructure development elsewhere, All Aboard Florida needs to prove its trains can make money. There are many doubters. They point to lawsuits, angry neighbors, construction delays, safety questions and political interference. All Aboard Florida has so far struggled to show it can put together a financing package that will attract investors, operate in the black and provide Floridians with a new transportation option that could reshape the state for years to come. No matter how high the hopes may be, if the finances don’t pencil out, the rest is just fanciful thinking.

(Governing discussed this story with an All Aboard Florida representative for six months, and, at the company’s request, pushed back publication to accommodate delays in Brightline’s scheduled South Florida opening, which finally occurred last month. Ultimately, however, the company declined to make anyone available for an interview or to submit answers to written questions. Governing drew from public statements, regulatory filings, court documents and news accounts to provide information about the company and its operations.)

Florida today might seem like an odd place to build new intercity rail, but it was rail that transformed the state from a sparsely inhabited swamp to a booming vacationland a century ago.

Henry Flagler, a founder of Standard Oil, built a rail line and accompanying hotels that pushed the Florida frontier down the Atlantic coast from Jacksonville until it reached Key West. That line led to the creation of West Palm Beach and the incorporation of Miami. The line Flagler built, the Florida East Coast Railway, stopped serving Key West after a hurricane in the 1930s, and it stopped carrying passengers entirely in 1968. But it’s the same route that Brightline trains would travel on for most of their journey between Miami and Orlando.

A rendering of the MiamiCentral train station. (Brightline)

To follow the finances of Brightline, it’s helpful to know that Fortress Investment Group, a private equity firm from Wall Street, owns Florida East Coast Industries, which in turn owns All Aboard Florida, which operates Brightline. None of them own the track, or the freight railroad that uses it, but they have a long-term agreement to give them access.

Car-saturated though it may be, Florida is an attractive place to build higher-speed passenger rail because it is flat. That makes track upgrades simpler -- and less expensive -- and makes it easier for trains to get up to speed. The fact that All Aboard Florida has access to existing tracks and rail rights-of-way all along the coast generally eliminates the need to take additional private property, which can be a legally onerous and politically fraught task. The company’s plans largely avoid that problem even in the areas where it will have to build new track, because the new rail line will follow an existing state highway from Cocoa (near the Kennedy Space Center on the Atlantic Coast) to the Orlando airport.

The distance between Orlando and South Florida is another factor that makes rail service attractive. Brightline will be too slow to qualify as true high-speed rail, like the 200 mph bullet trains that service cities in Europe and Asia, but it will achieve speeds similar to the Acela on Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. The distance from Miami to Orlando is too long for many drivers and too short for flying, which is the sweet spot for passenger rail (one reason why the Northeast Corridor, from Boston to New York to Washington, is Amtrak’s most popular route).

Connecting Orlando to South Florida would also link Florida’s top tourist destinations. Supporters hope the easy access between cities will encourage visitors to tack on a few extra days to their vacations, so that cruise passengers and beachgoers in Miami could also visit Walt Disney World and Central Florida’s other famed theme parks with little extra hassle.

For Brightline’s southern stretch, stations in the heart of Miami, Fort Lauderdale and West Palm Beach have been designed to appeal to residents who want to enjoy walkable amenities in city centers. That’s especially true in the newly resurgent downtown Miami. Brightline’s MiamiCentral train station will span six blocks in a formerly drab corner of downtown. The tracks are elevated 50 feet above street level, held up by V-shaped columns. Below the tracks, glass-enclosed retail spaces will line the streets, while above, towers will provide 800 rental apartments, a valuable commodity in an area where the number of residents has doubled since 2000. “The private sector can move things faster sometimes than government,” says Alyce Robertson, the executive director of the Miami Downtown Development Authority, a city agency. “The station went up like magic. It seems like they were just breaking ground, and now it’s beautiful. The architecture is also not the standard-issue value engineering you see in government buildings. Pretty soon, we are going to have a new service here unlike anything we’ve ever seen.”

An interior rendering of the train station at the Orlando airport. (Brightline)

Brightline has the potential to reshape the area’s other transportation offerings as well. MiamiCentral’s location next to the busiest stop on the county’s light rail line and next to the downtown people mover will make transferring among the different systems easy. Even more important, Brightline will share its southernmost tracks and MiamiCentral station with the area’s commuter rail service, Tri-Rail, which connects Miami-Dade, Broward and Palm Beach counties. The Brightline connection will allow Tri-Rail for the first time to drop its passengers off downtown instead of at the airport or a transfer station northwest of the city.

Local governments have spent $69 million to bring Tri-Rail into MiamiCentral. Bonnie Arnold, a spokeswoman for the South Florida Regional Transportation Authority, which operates Tri-Rail, says the benefits of the new station go beyond convenience. “You’re going to know you really arrived somewhere when you get there,” she says. “It’s what you think train stations ought to look like. It’s going to set Miami on fire for places people want to go.”

And one day, it might do that. But in the meantime, there are plenty of Floridians who don’t like Brightline and some who would be just as happy if it remained unfinished. The most vocal opponents are people living near the center of the route, who will see trains speeding by but get little benefit from them. That’s a region called the Treasure Coast, just north of West Palm Beach. County, state and federal officials from the area have tried to put the brakes on the project. Opponents have raised concerns about unsafe pedestrian crossings, blockage of emergency vehicles, environmental impact and additional expenses for local governments.

Debbie Mayfield, who represents much of the Treasure Coast in the state Senate, is pushing legislation to give the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) more power to enforce safety standards on railroads that operate at speeds greater than 80 mph. That would require Brightline or any future high-speed railroad to put up fencing in areas where there are a lot of pedestrians, roll out better train controls to prevent derailments like the one in Washington state in December and install remote systems to warn when crossing gates aren’t working properly. Mayfield also worries that local governments, which had agreed to pay for maintenance of railroad crossings when they only handled slower-moving freight trains, will now be on the hook to pay for upkeep of the far more expensive gates required for the private Brightline. Mayfield’s legislation has cleared one committee, but it is still a long way from reaching the governor’s desk.

Mayfield, though, says she would be “absolutely OK” with Brightline if her bill became law. “We are not trying to kill it,” she insists. “We are elected to ensure the safety of the citizens of Florida and to protect taxpayer money. That’s what I care about it.”

The railroad's safety quickly became an issue as service began in January. The day before its formal launch, a Brightline train struck and killed a pedestrian who reportedly crossed the tracks while the gates were down. Days later, another Brightline train killed a cyclist who tried to beat a train. It was the fourth fatality Brightline's trains were involved in since July. Both of Florida's U.S. senators, Republican Marco Rubio and Democrat Bill Nelson, asked federal railroad regulators to investigate the deaths and address railroad crossing safety in the region.

Florida has been debating, studying and planning high-speed rail for decades. Before Brightline, though, the closest it came to building it was in 2010 when the Obama administration, with the backing of then-Gov. Charlie Crist, announced it would pay for an 85-mile segment from Tampa to Orlando, with plans to extend the line later to Miami. But in February 2011, shortly after Crist left office, his successor, Gov. Rick Scott, rejected the $2.4 billion in federal funds to build the high-speed rail. Scott doubted that the line would attract as many riders as its planners claimed, and said that Florida would be on the hook for any cost overruns. “The truth is that this project would be far too costly to taxpayers, and I believe the risk far outweighs the benefits,” he told reporters.

A little more than a year later, in March 2012, All Aboard Florida first revealed its plans to build the Orlando-to-Miami line without public money. “This privately owned, operated and maintained passenger rail service will be running in 2014, at no risk to Florida taxpayers,” its materials said at the time.

But soon after All Aboard Florida unveiled its project, it became clear that state support would be needed, even if that didn’t come in the form of a direct subsidy.

Almost immediately, the railroad started negotiating with Florida for the right to build its Orlando extension along a state highway. FDOT provided the Orlando airport with $159 million in grants and $52 million in loans to build a new station that will service Brightline trains once they start running. All Aboard Florida pitched in $10 million to build the station and will pay $2.8 million a year in rent, plus per-passenger fees, to the airport.

(David Kidd)

Scott supported the All Aboard Florida bid. “All Aboard is a 100 percent private venture. There is no state money involved,” the governor said in 2014. (The fact-checking service PolitiFact has rated that statement “mostly false,” because of the state and federal benefits All Aboard Florida has already received.)

All Aboard Florida has enjoyed good relationships with the Scott administration. Adam Hollingsworth, a campaign adviser to Scott and the governor’s chief of staff from 2012 to 2014, worked as an executive at one of All Aboard Florida’s sister companies after the campaign and prior to becoming Scott’s top aide.

According to a 2016 New York Times report, Hollingsworth was involved in Scott’s decision to reject the Obama stimulus money for high-speed rail, and he pushed the governor to support the Brightline concept. Hollingsworth also helped introduce the governor to Wes Edens, a co-founder of Fortress Investment Group, the owner of All Aboard Florida.

Once Hollingsworth became Scott’s chief of staff, he recused himself from matters involving the railroad. But Fortress still worked closely with the Scott administration. That was evident when the company asked the Florida Development Finance Corporation, a nonprofit arm of the state, to issue $1.75 billion in tax-exempt bonds on its behalf. The “private activity bonds” allow private developers to pay off their debt at lower rates, because the proceeds from those bonds are exempt from federal income taxes.

The board ultimately gave the company permission to sell the bonds. The only problem was, the company couldn’t find enough people to buy them.

All Aboard Florida says it has already spent $2 billion to improve its freight lines, add a second track along its existing route, build stations, and buy trains and other equipment. But it’s also looking for long-term financing to cover the remaining cost of the project. That has not been an easy sell.

Originally, the company applied for a $1.6 billion loan from the federal government that would allow it to borrow money at the same interest rate as the federal government does. But getting a federal Railroad Rehabilitation and Improvement Financing (RRIF) loan can be difficult because of mandated environmental reviews, hefty upfront costs and a notoriously slow application process.

In congressional testimony last summer, Mike Reininger, the former CEO of Brightline and now the executive director of Florida East Coast Industries, its immediate owner, said the federal environmental review process was too cumbersome and that RRIF and other infrastructure financing programs “suffer from opaque and complex rules which discourage pursuit of these options and render them underutilized.”

Whatever the reason, All Aboard Florida walked away from its application for the federal railroad loan, after it spent two years going through the environmental review process. The Federal Railroad Administration issued a final environmental impact statement for the entire Miami-to-Orlando route, one step away from final federal approval, before All Aboard Florida opted instead to pursue another financing mechanism: the private activity bonds.

The company tried several times to find buyers for the bonds. In August 2015, it offered a 6 percent interest rate for the entire $1.75 billion. When that didn’t work, it raised the rate a month later to 7.5 percent. It tried a third time in October, keeping the rate at 7.5 percent but offering better terms for buyers. A fourth revision in November also yielded no results.

The attempted sales did, however, trigger federal lawsuits by two Treasure Coast counties that Brightline trains would pass through -- but not stop in -- between West Palm Beach and Orlando. After more than a year, Indian River and Martin counties cleared a major legal hurdle to challenge the company’s ability to issue the bonds. All Aboard Florida short-circuited the lawsuit by changing its financing plan yet again. It told the court it would break up its bond offerings to match the phases of the project. For now, it would seek to sell only $600 million in bonds to cover the costs of its Miami-to-West Palm Beach segment. At some time in the future, it would look to sell the remaining $1.15 billion to finance the extension to Orlando. Practically, this meant that there would be no bonds for the improvements in the Treasure Coast counties, which negated their lawsuit. The judge dismissed the suit last May.

But the lawsuit did reveal how tenuous the company’s plans were for financing its second phase. In one of his rulings, U.S. District Judge Christopher Cooper concluded in 2016 that All Aboard Florida had almost no choice but to sell private activity bonds to pay for the Orlando expansion. That approach “is not the current financing plan for the project -- it appears to be the only financing plan,” he wrote, relying in part on proprietary business information that he kept under seal. All Aboard Florida told federal regulators that the tax-exempt bonds were the “linchpin for completing our project,” the judge noted.

One reason Cooper made his comment was that Fortress, the ultimate owner of Brightline, was itself in financial trouble. Its market capitalization shrank by more than half just in the time the lawsuit was pending. Other potential sources of finances also posed problems. For example, a company lawyer said in court that Brightline could not afford to pay interest rates of 12 percent for corporate debt for the entire project, the rate a plaintiff’s expert said would be necessary to fund it privately. Plus, the federal railroad loan seemed to be off the table, because the company stopped pursuing it.

Since Cooper made that ruling, though, many aspects of the railroad’s situation have changed. First, a Japanese telecommunications giant, SoftBank, announced last February that it would buy Fortress for $3.3 billion, a significant markup from its market value. (The sale was finalized late last year.) In July, Brightline applied again for an RRIF loan, asking for $3.7 billion.

Once completed, Brightline will run from the Orlando airport to downtown Miami. (Brightline)

Then, in October, the company got the Florida development board’s permission to issue $600 million in private activity bonds to help pay off debts it incurred building the South Florida portion of Brightline, in particular $504 million for a high-interest loan it took out in 2014 and a separate $98 million debt to the manufacturer from which it bought its five trains.

Fitch Ratings gave Brightline bonds a BB- rating, which is three notches below investment grade. The agency’s analysts were concerned about whether there would be enough demand for Brightline’s services and, if so, how quickly it would ramp up. Part of Brightline’s problem is that there are no projects to compare it to. This is the first one of its kind in decades. “Seeing demand even relatively close to All Aboard Florida’s forecasts in an area like southeast Florida, which has this auto focus, would show there is a market for this sort of rail and that there is potential for other city pairs for high-speed rail,” says Stacey Mawson of Fitch. But the proof doesn’t yet exist.

In December, the Federal Railroad Administration finally issued its long-delayed record of decision for the entire project, the final administrative step of its environmental review, which allowed the project to go forward.

On balance, the most recent developments seem to have put All Aboard Florida in a better position than it was in a year ago. The best news for the company is that the first Brightline trains began service last month between West Palm Beach and Fort Lauderdale, and it’s likely the cheerfully colored trains will be rolling into Miami soon. What’s a lot less clear is when -- or even if -- they’ll make it to Orlando, where, at the airport, a soaring, modern intermodal center, built with public money, nears completion and awaits its first privately funded train.

*This story has been updated from the original version, which appears in the February issue of Governing's print magazine.