That’s the conclusion of a new report from the Commonwealth Fund, a health policy research organization that analyzed regulations in place the month Obamacare plans took effect and one year later, in January of 2015.

For the first time ever, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) set a national standard for health insurers on the private market to follow when creating networks with enough doctors in enough places. That standard started in January of 2014, when policies sold through ACA exchanges took effect. About 15 million people, largely those without employer health insurance, buy their plans on this market.

But the national standard is broad, requiring insurers to maintain “a network that is sufficient in number and types of providers” to ensure access to services “without unreasonable delay.” It’s state departments of insurance that are largely the ones determining whether an insurer is following that guideline, and states are also allowed to set their own, more detailed, rules.

Soon after, and even before, ACA plans took effect, stories surfaced about people losing their doctors because of narrow plans. Those anecdotal examples have continued, though there’s not yet been a comprehensive study comparing Obamacare plans with their predecessors on the individual market.

Insurers have long tried to minimize the size of their networks to boost their negotiating power and keep premiums lower. But states can limit just how narrow through specific, quantitative rules. Those standards typically take the form of maximum travel time for an enrolled patient to see a doctor, doctor-to-enrollee ratios, maximum appointment wait times and offering extended hours.

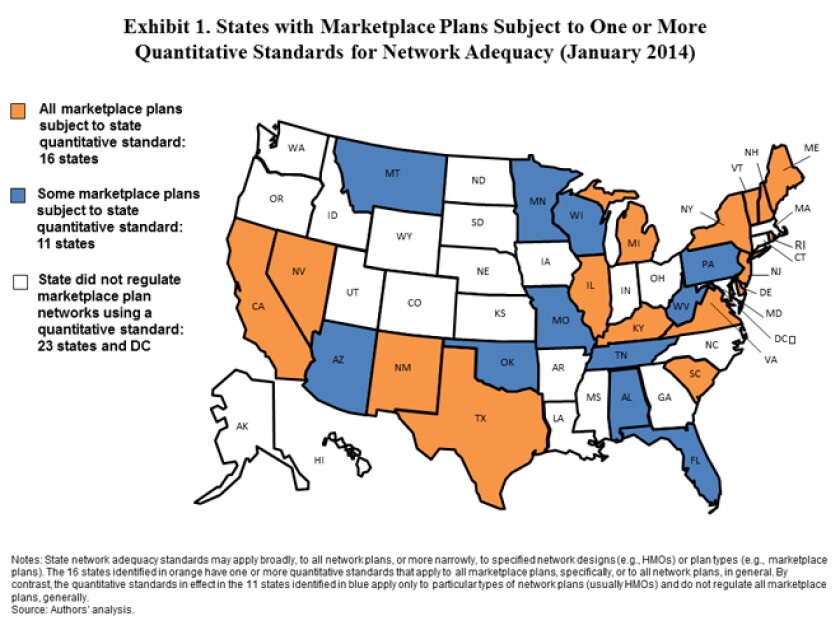

As Obamacare plans took effect in January 2014, 27 states required at least some marketplace plans to satisfy a quantitative measure of network adequacy, according to the Commonwealth Fund’s report. The most common measure is maximum travel time or distance, with 23 states observing that requirement. The distance rule can vary by state and type of plan. For some Minnesota plans, for instance, the maximum is the lesser of 30 minutes or 30 miles to the nearest primary care, mental health or general hospital service. California appears to have the toughest standards, using each of the four main network rules. Additionally, 10 states in 2014 required insurers to update directors of available doctors at least twice a year.

(Source: The Commonwealth Fund)

Not much changed in a year. By January of 2015, three states added new quantitative requirements. Arkansas added distance standards, California broadened its wait time requirements and Washington added a range of new rules. Another six states tightened rules for updating doctor directories, while at least six states gave their insurance regulators stronger enforcement power.

Commonwealth argues the relatively limited number of new quantitative rules makes sense as states try to balance access with prices. “There is evidence that some states may have been reluctant to act too aggressively or too quickly in the absence of robust market data and feedback from consumers and stakeholders about their experiences with narrow network marketplace plans.”

There are also signs the pace might pick up. By January of 2015, four states and the District of Columbia had started exploring new regulatory rules.