The good news for states and localities is that it isn't their IOU. The bad news is that it affects their revenues. Young people saddled with debt don't form households as they come out of college. Instead, many of them are moving back home with their parents, which has a depressing effect on an already troubled housing market. Students saddled with debt also tend to cut back on other spending as well -- spending that would otherwise boost sales taxes. The trend is worrisome.

Right now, some 37 million students or graduates owe money on a student loan, according to the New York Federal Reserve. The average borrower owes about $23,000. These startling statistics have brought on talk of a student loan bubble that could burst at any time, bringing a wave of defaults.

Given the connection between privately held student debt and the public purse, is there anything states and localities could or should do about it? I talked about the issue with Daniel Burrus, CEO of Burrus Research and author of Flash Foresight. Here are highlights of our conversation.

How did student debt get so big?

Part of what has driven the debt up so high is the recession. So many people were laid off, and a lot of them decided to go back to school. A lot of them took out loans, which helped to mushroom the debt number. At the same time, universities and technical schools had more people applying than ever before. When there is way more demand than supply -- you have only so many professors and seats -- you can charge more. So student costs rose and the debt grew.

Another element making the problem worse faster is that a lot of those students that were laid off and went back to school had no income. They were high risk, yet they were able to get a student loan. That means the default rate of those loans will be higher than normal. Thirty percent of student loans have missed a month [on their repayment schedule].

Amount of Student Debt Taken Each Year

Credit: Lam Thuy Vo/Planet Money

What could state or local governments do to ease the problem?

I surveyed students recently. One was a sophomore in college, majoring in philosophy. I asked him if he was planning to get a masters or Ph.D. when he graduated, or if he planned to get a job. He planned to get a job. Well, the guidance counselor didn't tell him that he can't get a job with a degree in philosophy unless he has a Ph.D. A simple thing that can be done is to show students in high school and college the areas they might study and the degrees they'll need in order to get a job. Local governments can make sure they are doing something to educate state and local guidance counselors to provide better counseling so you don't end up with kids that can't get work.

Beyond guidance on areas of study, what else could states or localities do?

Not every state is rewarding positive behavior. States -- like Florida, Georgia and a few others -- have said that if a student earns a 3.0 average or higher in high school, college tuition is free if they attend an in-state school. They are using lottery money to fund this. It serves the state well because their good students stay in the state.

There's another behavior states could reward: What if we gave some tax incentives for getting degrees in subject areas we need? Hundreds of thousands of jobs are available right now in science, math and engineering. We don't have enough students picking those majors. If a student gets a degree in science, math or engineering and gets a job in that field, her debt could be reduced by lowering her tax to help pay off that debt.

Not all students are going to go to a four-year college. We need machinists and fiber installers. We're about to have a shortage of plumbers and professions like that. Why? Because baby boomers are retiring. Do the guidance counselors know? States should be talking to the major employers in their states to find out what they are worried about as they look at workforce retirements. Then they should make sure they are letting students know what jobs will be there and guide them in what classes to take.

This is not rocket science. It's stuff that can be done.

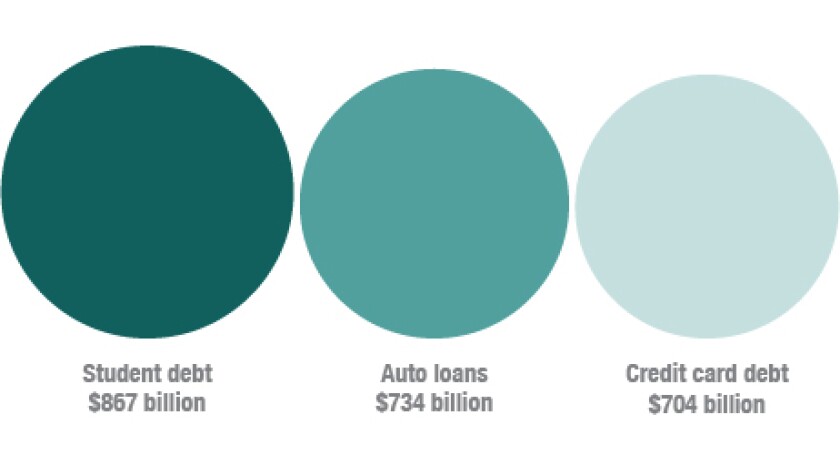

Student Debt Vs. Credit Card Debt

Credit: Lam Thuy Vo/Planet Money

Those sound like preventive measures. What about the students who are in debt now? Are there ways for states to help them?

There needs to be strategic planning at the state and national level regarding student debt and the rising cost of tuition. Is there a way we can work with our for-profit universities and education institutions? Are there rewards that will keep them from raising tuition?

We also need to look at how students can pay back that loan. Student loans are considered delinquent if they miss nine months of payments. Then, all the money is due immediately. Given the depths of this recession, maybe we need to revisit that.

Unlike the housing bubble that threw us into a recession quickly -- everything came due at once because five-year adjustable mortgages came due --student defaults are staggered. They won't all face the problem at same time. That eases the problem. But it's still an issue we need to do something about.