Most municipalities have done some work in at least one of these areas. But to unleash the full potential of data, a city needs a coordinated strategy that overcomes procurement obstacles while encompassing each pillar of its data-directed work. Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter set out to change the data and performance culture of his city during his two terms, which ended in January.

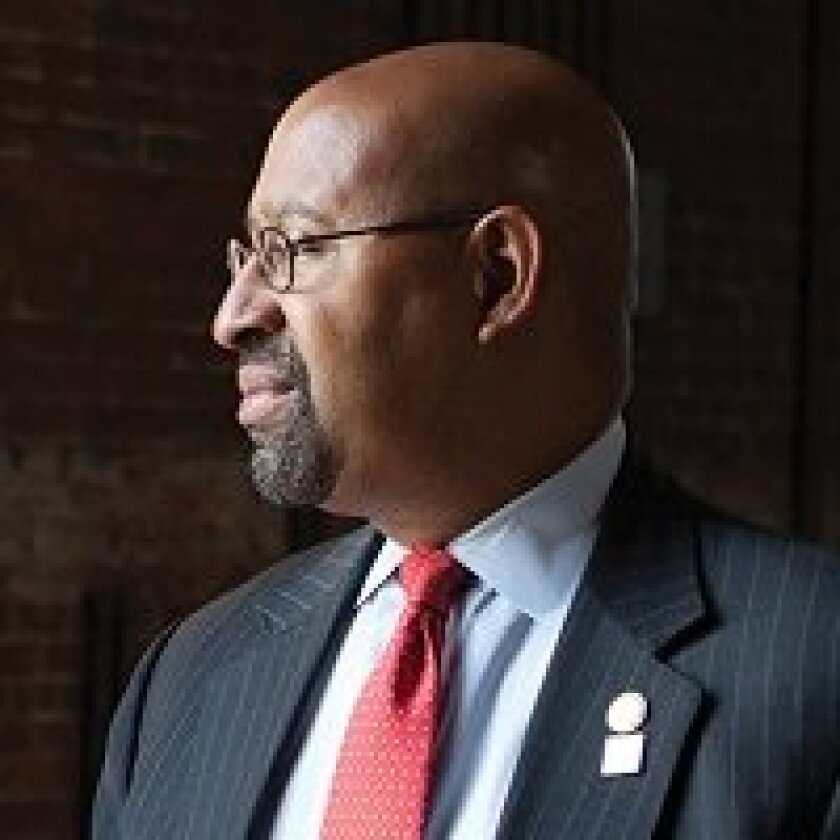

Nutter, who was honored by Governing as a Public Official of the Year in 2014, is now a professor of practice in urban policy at Columbia University, a What Works Cities Senior Fellow and a commentator for CNN. He and I recently discussed his priorities and approach to infusing the culture of municipal government with a steadfast commitment to data and measurable results. Here are excerpts from our conversation:

Stephen Goldsmith: Let's start with the big picture. You get elected mayor of Philadelphia and have a vision. How did you connect that vision with metrics?

Michael Nutter: We needed to transition to a more complete sense of measurement. There was not a whole lot of conversation going on between departments. The impact of the recession forced us in many instances into much more collaborative processes. Mayors and cities learn from each other. Results were starting to be shown from much of what was happening in New York City and other places. Over the next couple of years, it became increasingly clear that we had a lot of data, but we weren't always using the data to maximum advantage. We were collecting data because we are the government so we collect a lot of things. The industry of data analytics was starting to really grow and manifest itself, and we created a data unit with a chief data officer. All of those kinds of things started coming into play between 2011 and 2013. It made a tremendous difference.

|

|

| Michael Nutter |

Goldsmith: When did your performance data meet up with your open data?

Nutter: Open data was in the middle of my eight years when we really got serious and brought on a chief data officer and started releasing these datasets. I think the public was surprised, the press was surprised, our own employees were surprised. I reminded them that part of what I ran on was openness and transparency. There have been other very positive outcomes -- entrepreneurs and the startup community are using some of that data and creating apps or new businesses. A part of this is really all about transparency and openness and integrity, but also a better relationship with your citizens. Initially, people just thought we would do a little bit. But we have hundreds of datasets that have now been released from virtually every department and agency in the government. I'm not sure if we even send out press releases anymore about the release of data. It's become the norm.

Goldsmith: Did you see any difference in the organization's commitments to data when the open data was layered on top of performance data?

Nutter: It has given people more confidence, a greater comfort level in releasing information, and it has reinforced that we are a large service organization. Our job is to deliver services to the people. And if we aren't measuring ourselves, then what are we even doing? How do we convey to the public that we are doing our jobs? /p>

Goldsmith: As a What Works Cities fellow, what advice would you give to What Works Cities mayors?

Nutter: The first piece of advice that I always give mayors is: "Have a plan; work your plan; stick to the plan." As a WWC mayor, it is critically important to consistently communicate to your staff, the city workforce and, most importantly, the public, how the What Works Cities goals of using data and evidence to inform decisions fits in the plan and advances the work and issues that you campaigned on to become mayor. You also need to report out to the public on a regular basis with honest assessments of success and efforts that may have fallen short or not worked. Having and maintaining integrity and credibility in this process is critical to the success of the open data movement.

Goldsmith: If you look back at your last day as mayor, and the data and evidence tools you had then compared to your first day, how do you characterize the change?

Nutter: I think it's light years of difference. This area is only going to grow. It's only going to get better. It's not a fad. And quite honestly it's one of the most essential tools that a mayor or chief executive can ever have in terms of trying to run the city.